Your cart is currently empty!

A Tiny Tweak to LSD Just Produced a Drug That May Repair the Brain

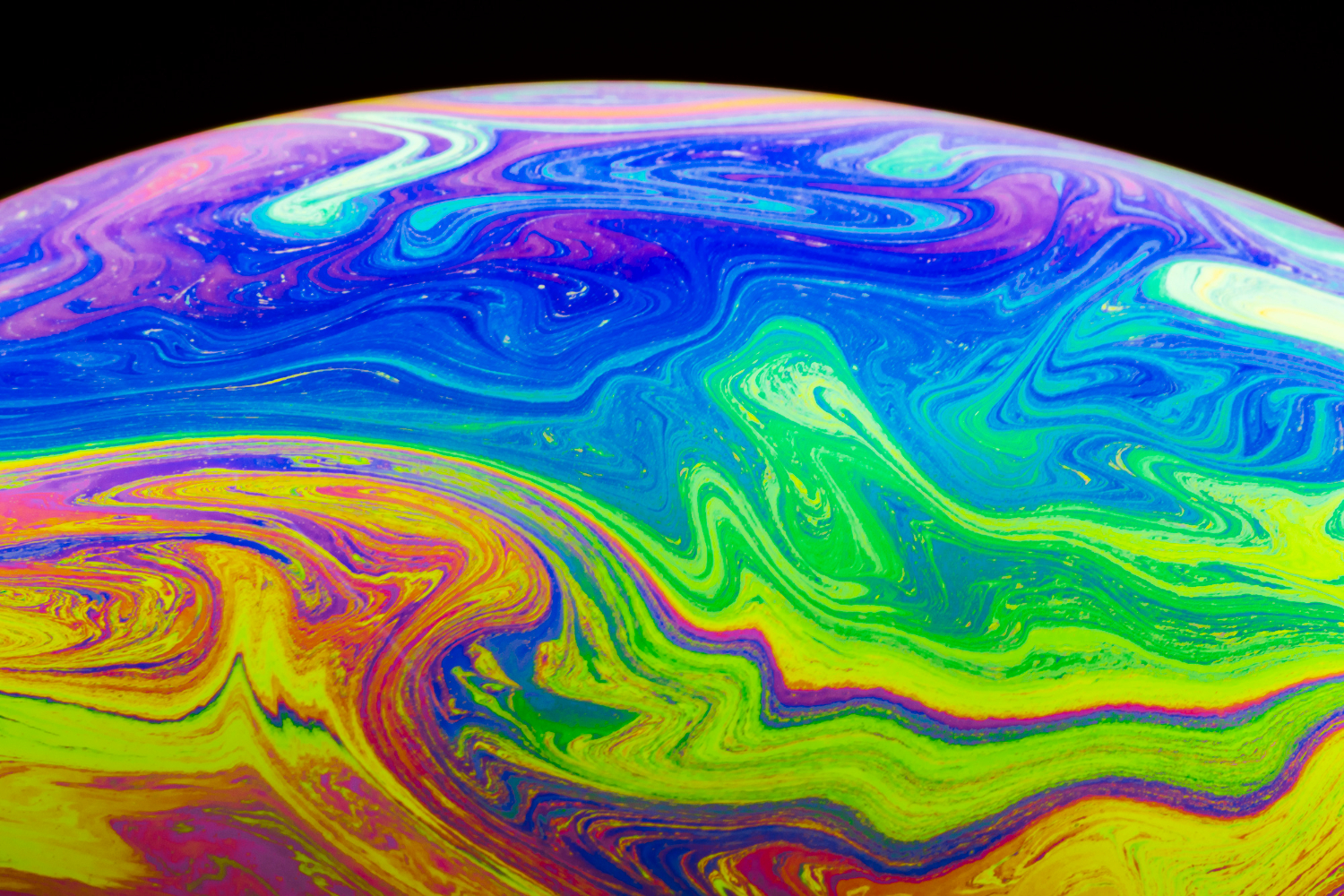

Somewhere in a lab at the University of California, Davis, a chemist made a decision so small it barely registered as a change at all. Two atoms. That was it, just two atoms swapped from one position to another inside one of the most notorious molecules in pharmaceutical history. What came out the other side was not the psychedelic that defined a generation of counterculture. It was something far more medically interesting, and potentially far more powerful.

Meet JRT, a compound quietly derived from LSD that, according to early research, can repair damaged brain connections, lift depressive symptoms, and may one day treat conditions that current medicine has largely failed to address. No hallucinations required.

A “Tire Rotation” That Changed Everything

LSD has long fascinated researchers not just for its hallucinogenic properties, but for what it does to the brain at a structural level. Unlike many psychiatric drugs that simply adjust chemical signals, LSD can prompt neurons in the prefrontal cortex to grow new branches and form fresh connections, a process scientists call neuroplasticity. For people whose brains have been worn down by chronic stress or mental illness, that kind of physical repair sounds less like pharmacology and more like science fiction.

But LSD comes with an obvious problem. Its hallucinogenic effects make it unsuitable for many patients and outright dangerous for others. So David E. Olson, a chemistry professor and director of UC Davis’s Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics, set out to do something precise: strip the psychedelic out of LSD while leaving its brain-repairing properties intact.

His solution was elegantly simple, at least in theory. “Basically, what we did here is a tire rotation,” Olson said. “By just transposing two atoms in LSD, we significantly improved JRT’s selectivity profile and reduced its hallucinogenic potential.”

That atomic swap took nearly five years and a 12-step synthesis process to pull off. Graduate student Jeremy R. Tuck was the first to successfully produce it, which is how the compound got its name. What Olson and his team ended up with was a molecule that shares LSD’s molecular weight and overall shape but behaves in an entirely different way once it enters the brain.

How JRT Works Without the Trip

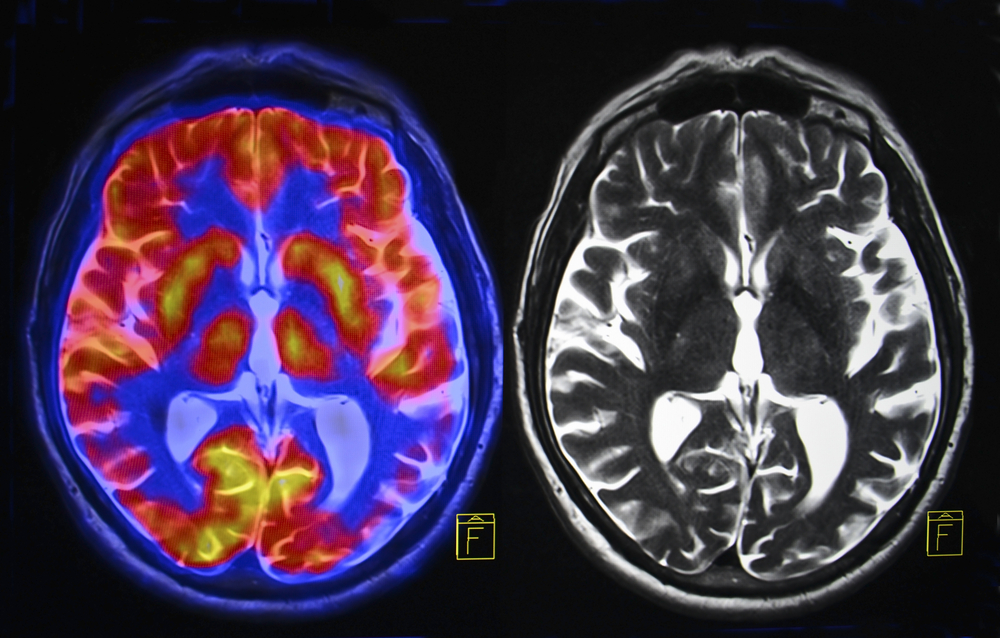

To understand why JRT matters, it helps to know a little about what goes wrong in the brains of people with depression, schizophrenia, or other neuropsychiatric conditions. In many of these cases, the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for decision-making, emotional regulation, and social behavior, shows measurable structural damage. Dendritic spines, the tiny branches that neurons use to communicate with each other, shrink or disappear. Synaptic connections weaken. Over time, that loss shows up as symptoms.

Most psychiatric drugs do not address this structural damage. They manage brain chemistry, adjusting levels of serotonin or dopamine, but they do not rebuild what has been lost. JRT, like LSD, belongs to a different class of molecules called psychoplastogens, which work by physically prompting the brain to grow new connections.

In preclinical studies, a single dose of JRT produced a 46% increase in dendritic spine density and an 18% increase in synapse density in the prefrontal cortex of mice. When researchers looked at mice that had been put through a chronic stress protocol designed to mimic cortical atrophy, JRT reversed the damage within 24 hours of a single dose. JRT does this by binding selectively to serotonin receptors, specifically the 5-HT2A receptors that sit at the center of both psychedelic drug action and neuroplasticity. Unlike LSD, which also interacts with dopamine, histamine, and adrenergic receptors, JRT keeps things selective. That selectivity is part of what makes it potentially safer.

The Schizophrenia Problem and Why JRT Is Different

Of all the potential applications for JRT, its possible role in treating schizophrenia may be the most striking and, for anyone familiar with the field, the most surprising.

Schizophrenia is a condition marked by a wide range of symptoms. Hallucinations and delusions are the most visible. But patients also experience anhedonia, a loss of pleasure, social withdrawal, and significant cognitive impairment. Current antipsychotics do a reasonable job of managing hallucinations through dopamine receptor blocking, but they have long struggled with the negative and cognitive symptoms. Clozapine, often considered the most effective antipsychotic available, has proven more capable on these fronts but carries a difficult side effect profile, including weight gain, sedation, and metabolic dysfunction.

Psychedelics, meanwhile, have been explicitly ruled out for schizophrenia patients. Emergency department data have linked hallucinogen use to a higher risk of developing psychosis-spectrum disorders. Giving LSD to someone already experiencing hallucinations would be genuinely dangerous.

JRT appears to sidestep that problem entirely. “No one really wants to give a hallucinogenic molecule like LSD to a patient with schizophrenia,” Olson said. “JRT’s development emphasizes that we can use psychedelics like LSD as starting points to make better medicines. We may be able to create medications that can be used in patient populations where psychedelic use is precluded.”

In mouse studies, JRT improved the cognitive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as social withdrawal, cognitive fog, and reversal learning deficits, without triggering the behavioral hallmarks of hallucinogenic drug action. Researchers measure hallucinogenic potential in mice using a test called the head-twitch response, which correlates strongly with hallucination-producing effects in humans. JRT produced no significant head-twitch response at any dose tested. It also did not trigger the gene expression patterns associated with schizophrenia that LSD reliably produces.

Perhaps more telling, pretreatment with JRT actually blocked the head-twitch response caused by LSD, a behavior more consistent with an antipsychotic than a psychedelic.

A Depression Treatment 100 Times More Potent Than Ketamine

Schizophrenia is not the only area where JRT produced striking results. When researchers ran JRT through a battery of depression-related tests, what they found stopped them in their tracks.

Ketamine is currently considered among the fastest-acting antidepressants available, often used for treatment-resistant cases, and serves as the benchmark. JRT outperformed it at roughly one-hundredth of the dose. In the forced swim test, a standard preclinical measure of antidepressant potential, JRT worked at doses so low that researchers described it as at least 100 times more potent than ketamine.

What made this particularly interesting was the duration of the effect. JRT cleared from rat blood and brain tissue within two hours of administration, yet its antidepressant effects persisted well beyond that window, including in models of stress-induced anhedonia, where animals treated with JRT maintained improvement for days after a single dose, even under continued stress.

Researchers also tested JRT against anhedonia using a probabilistic reward task, a behavioral measure considered highly translatable between animals and humans. Chronic cold-water stress reduced animals’ ability to respond adaptively to rewards, a pattern that mirrors what happens in human depression. JRT restored that response, and the effect held for at least three days after a single administration.

What JRT Does Not Do

Any discussion of a drug derived from LSD naturally raises questions about side effects. So it is worth being clear about what JRT did not do in preclinical testing.

JRT did not produce hallucinogenic behavior. It did not worsen psychosis-related symptoms. It did not cause sedation. It showed no affinity for dopamine receptors, which means it avoids the movement-related side effects known as extrapyramidal symptoms that plague many traditional antipsychotics. Unlike clozapine, which blocks 5-HT2C receptors and is believed to contribute to weight gain and metabolic problems as a result, JRT acts as a potent agonist at these same receptors, suggesting a potentially cleaner metabolic profile.

One area of ongoing attention is JRT’s partial agonism at 5-HT2B receptors. Chronic stimulation of that receptor has been associated with cardiac complications in some other drugs. Researchers have flagged it as something to watch as studies continue.

Where Things Stand and Where They’re Headed

JRT has not been tested in humans. Every result described here comes from cell cultures and animal models, and the road from a promising mouse study to an approved medication is long, expensive, and frequently disappointing. Plenty of compounds that perform well in preclinical settings fail when they reach human trials.

That said, the science behind JRT is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, one of the most respected peer-reviewed journals in the world, and the research was funded by a broad consortium of institutions, including the National Institutes of Health.

Olson and his team are currently running JRT through additional disease models and working to improve its synthesis process. Researchers are also developing new analogues of the compound, essentially variants of JRT that might perform even better.

“JRT has extremely high therapeutic potential,” Olson said. “Right now, we are testing it in other disease models, improving its synthesis, and creating new analogues of JRT that might be even better.”

Olson also co-founded Delix Therapeutics, a company working to bring psychoplastogens to market, a signal that at least some in the investment world see commercial promise in this line of research.

A New Way of Thinking About Mental Health Treatment

What JRT represents, beyond its specific applications, is a shift in how researchers are approaching psychiatric medicine. Rather than treating the brain as a system of chemical signals to be nudged up or down, psychoplastogens treat it as a physical structure, one that can be damaged and, potentially, rebuilt.

For decades, the hallucinogenic properties of psychedelics kept them at the margins of mainstream medicine. Regulatory restrictions, social stigma, and genuine safety concerns kept LSD and its relatives out of clinical practice, even as evidence mounted that they might offer something genuinely therapeutic.

JRT suggests that the therapeutic and the hallucinogenic are not as inseparable as once assumed. By making a change so small it sounds almost trivial, moving two atoms, doing a “tire rotation,” researchers at UC Davis may have opened a door that neither psychiatry nor pharmacology has been able to walk through before.

Whether JRT eventually becomes a treatment that patients can access depends on years of additional research and regulatory review. But for now, it stands as a striking example of what happens when scientists look at one of the most notorious molecules ever discovered and ask a simple question. What if we could keep what works and lose what doesn’t?