Your cart is currently empty!

56 Percent Of Americans Don’t Think We Should Teach Arabic Numerals In School

Something troubling happened when 3,624 Americans answered what seemed like a straightforward education question. More than half said no to teaching a fundamental mathematical system in schools. CivicScience, a market research firm, posed a simple query about curriculum standards. What came back revealed something far more complex about how people process information when tribal instincts kick in.

Survey results showed 56 percent of respondents opposed including Arabic numerals in American classrooms. Another 29 percent supported teaching them, while 15 percent expressed no opinion. At first glance, these numbers might seem unremarkable. Poll any educational topic and you’ll find divided opinions. Parents, educators, and citizens regularly disagree about what belongs in curriculum standards. Except there’s a catch. A big one.

You’ve Been Using Them Your Whole Life

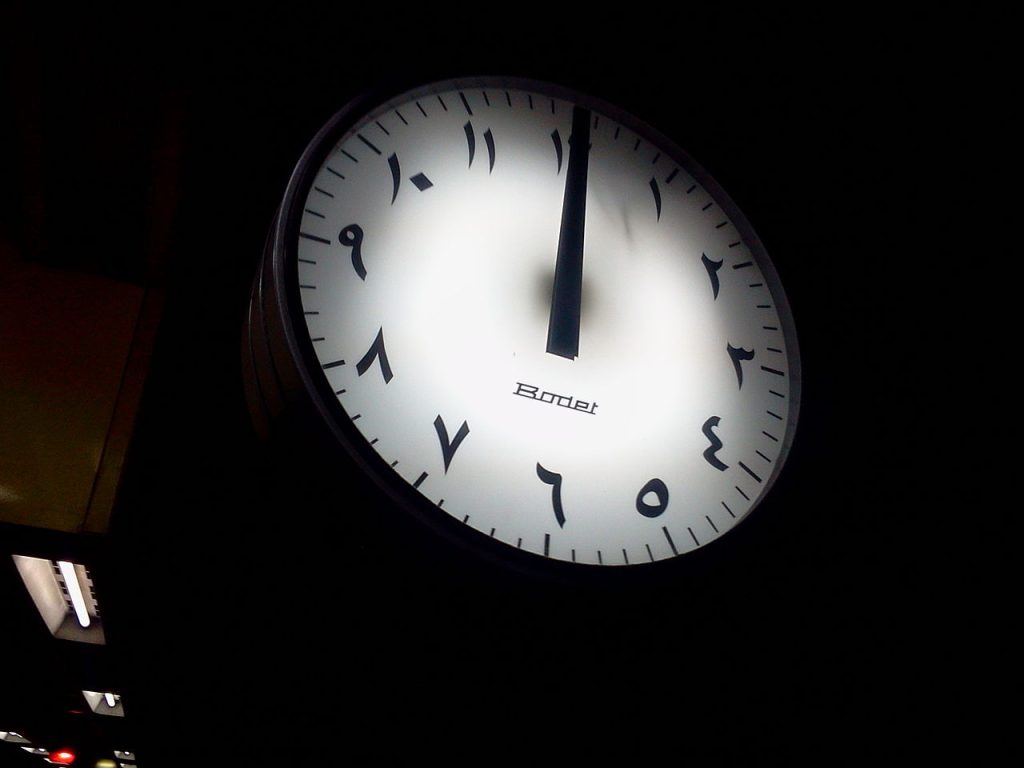

Arabic numerals are the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. Every number you’ve ever written, typed, or read uses these symbols. Right now, you’re looking at them. When you check your phone for the time, pay for coffee, or scroll through social media, Arabic numerals fill your screen.

Americans use this system every single day without thinking about it. So do people in England, France, Germany, and most other nations. Even in China and Japan, where traditional number systems exist, Arabic numerals appear regularly in business, science, and daily life. Unless you’re living in ancient Rome, you probably use them too.

So 2,020 people just voted against teaching the very numbers that make modern mathematics possible. People rejected the system they rely on to balance checkbooks, read addresses, and understand prices. John Dick, CEO of CivicScience, called the results “the saddest and funniest testament to American bigotry we’ve ever seen in our data.”

How CivicScience Set the Trap

Dick designed the survey with intention. CivicScience deliberately avoided defining what Arabic numerals meant in the question. No explanation appeared. No context was given. Respondents saw only the phrase and had to decide based on their gut reaction.

“Our goal in this experiment was to tease out prejudice among those who didn’t understand the question,” Dick explained on Twitter. Most people don’t understand where our number system originated. Yet they picked answers anyway, falling back on biases and assumptions rather than admitting ignorance.

Pollsters have used similar tactics before. Ask people questions loaded with unfamiliar terms or references, and watch how quickly they choose sides based on keywords rather than knowledge. When uncertainty enters the equation, tribal thinking often wins.

Party Lines and Number Lines Don’t Mix

Political affiliation split the responses in predictable ways. Republican supporters showed stronger opposition, with 72 percent saying Arabic numerals shouldn’t appear in the school curriculum. Democrats opposed them at a lower rate of 40 percent. Education levels between the two groups showed no major differences.

People with similar schooling answered differently based on political identity. Knowledge about numerical nomenclature was roughly equal across party lines. What changed was the reaction to the word “Arabic” itself. Republicans, who often express concerns about Islamic influence in American culture, rejected the concept more forcefully. Democrats, generally more accepting of multiculturalism, still opposed it at concerning rates.

Both groups failed the basic knowledge test. Yet one group showed more knee-jerk resistance to anything carrying an Arabic label. Politics poisoned math. Ideology trumped information. People who use these numbers every moment of every day couldn’t recognize them when presented with their proper names.

Democrats Had Their Own Blind Spot

Dick didn’t stop with one loaded question. CivicScience included another trap designed to catch liberal respondents in similar prejudice. Researchers asked whether schools should teach “the creation theory of Catholic priest Georges Lemaître” as part of the science curriculum.

Democrats opposed this at 73 percent. Republicans rejected it at only 33 percent. On its face, the results suggest Democrats want to keep religious teachings out of science classrooms. Progressive voters have long fought against creationism and intelligent design infiltrating biology lessons. Seeing “Catholic priest” and “creation theory” together likely triggered immediate rejection.

Except Georges Lemaître wasn’t teaching Genesis. Lemaître was a Belgian astronomer and cosmologist who studied physics at both Cambridge University and MIT. He proposed that the universe began from a single particle explosion and has been expanding ever since. Scientists confirmed his theory through observations. We now call it the Big Bang theory.

So Democrats just voted against teaching one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century because a Catholic priest proposed it. Dick noted the effect was almost identical to the Arabic numerals question. Both sides displayed bias. Republicans reacted against anything Arabic. Democrats reacted against anything religious.

Where These Numbers Actually Come From

Arabic numerals didn’t actually originate in Arabia. Indian mathematicians developed the system in the 6th or 7th century. Over time, Middle Eastern scholars adopted and refined these numbers. Al-Khwarizmi and Al-Kindi, two prominent mathematicians, introduced the system to Europe during the 12th century through their writings.

Europeans called them Arabic numerals because they learned the system from Arab scholars. Before this point, Western civilization relied on Roman numerals and counting tools like the abacus. Arabic numerals made complex calculations possible. Algebra emerged from this numerical foundation. Modern mathematics was built on these ten simple symbols.

Without Arabic numerals, contemporary science and technology couldn’t exist. Computer programming requires them. Engineering depends on them. Financial systems run on them. Every spreadsheet, equation, and algorithm needs the elegance and flexibility this system provides.

Yet more than half of the survey respondents wanted them banned from schools.

When Americans Have Done Something Like Before

CivicScience’s Arabic numerals survey echoes an earlier polling embarrassment. In December 2015, Public Policy Polling asked Americans whether the United States should bomb Agrabah. Results showed 41 percent of Trump supporters favored military action against the city. Nineteen percent of Democrats also supported bombing it.

Agrabah doesn’t exist. It’s the fictional setting of Disney’s animated film Aladdin. Princess Jasmine rules there alongside her father. Jafar serves as the villain. A magic carpet provides transportation. None of it is real.

But 30 percent of poll respondents wanted to bomb it anyway. People heard a Middle Eastern-sounding name and immediately jumped to supporting military intervention. No one asked where Agrabah was located. Nobody questioned whether it posed any actual threat. Voters simply saw an Arabic name and decided bombs were appropriate.

Both surveys reveal the same pattern. Present Americans with unfamiliar terms that sound Middle Eastern or Islamic, and prejudice fills the knowledge gap. Rather than admit uncertainty or request clarification, respondents default to opposition. Tribal instincts override rational thought.

Social Media Responded to the News

Twitter erupted when Dick shared the survey results. Users expressed shock, amusement, and dismay at the findings. Some responses turned the absurdity into humor. One user joked about returning to “Judeo-Christian values” by using Roman numerals for mathematics instead. Another posted fake poll results written entirely in Roman numerals, with “IXXX% IN FAVOR” and “LIV% OPPOSE.”

Others focused on the implications. How could so many people not recognize the term for numbers they use constantly? What does this say about American education? Are citizens really this susceptible to making decisions based purely on buzzwords and bias?

Dick’s original tweet sharing the Arabic numerals results got retweeted more than 20,000 times. People couldn’t believe the numbers. Many assumed the survey must be fake or the question must be misleading. But CivicScience confirmed the methodology. Real Americans gave these answers when asked straightforward questions about curriculum.

What Survey Says About How We Answer Questions We Don’t Understand

Blind prejudice appears easier than admitting ignorance. When faced with unfamiliar concepts, people could simply answer “I don’t know” or “no opinion.” Fifteen percent of respondents chose it for the Arabic numerals question.

But 56 percent picked a side instead. Rather than acknowledge gaps in their knowledge, they made decisions based on whatever triggered their gut reaction. Sometimes that trigger was political. Sometimes it was religious. Sometimes it was purely about ethnicity or perceived foreign influence.

Dick pointed out that both political tribes fell into the same trap. Neither side holds a monopoly on blind prejudice. Republicans demonstrated bias against anything labeled Arabic. Democrats showed bias against anything associated with Catholic clergy. Both groups answered questions they didn’t understand by falling back on preexisting prejudices.

CivicScience’s survey holds up a mirror to how modern Americans process information. Keywords trigger reactions before understanding develops. People pick teams and defend positions even when they don’t fully understand what they’re defending.

Arabic numerals built the mathematical foundation for everything from banking to space exploration. Yet given the choice, most Americans would remove them from classrooms simply because the name sounds foreign.

Ten simple digits keep working regardless of what we call them or whether we understand their history. But survey results suggest Americans might benefit from learning more about the tools we use every day before deciding they don’t belong in our schools.