Your cart is currently empty!

Warrior Buried 900 Years Ago May Have Been Non-Binary, Study Reveals

In a quiet field in southern Finland, archaeologists once uncovered a grave that refused to be simple. Inside lay the remains of a person buried with two swords, fine jewelry, and clothing typically worn by women during the early medieval period. At first, the find was marked as unusual but not urgent. Something about it didn’t sit neatly into what we thought we knew.

It wasn’t until years later, with the help of modern science, that researchers began to ask different questions. What if this wasn’t just a warrior? What if this was someone whose identity challenged the limits of how we define people today? And what does it mean that their community may have honored them fully for who they were?

Some graves reveal lives. This one might reveal a truth far bigger than a single name.

The Suontaka Burial: What the Grave Revealed

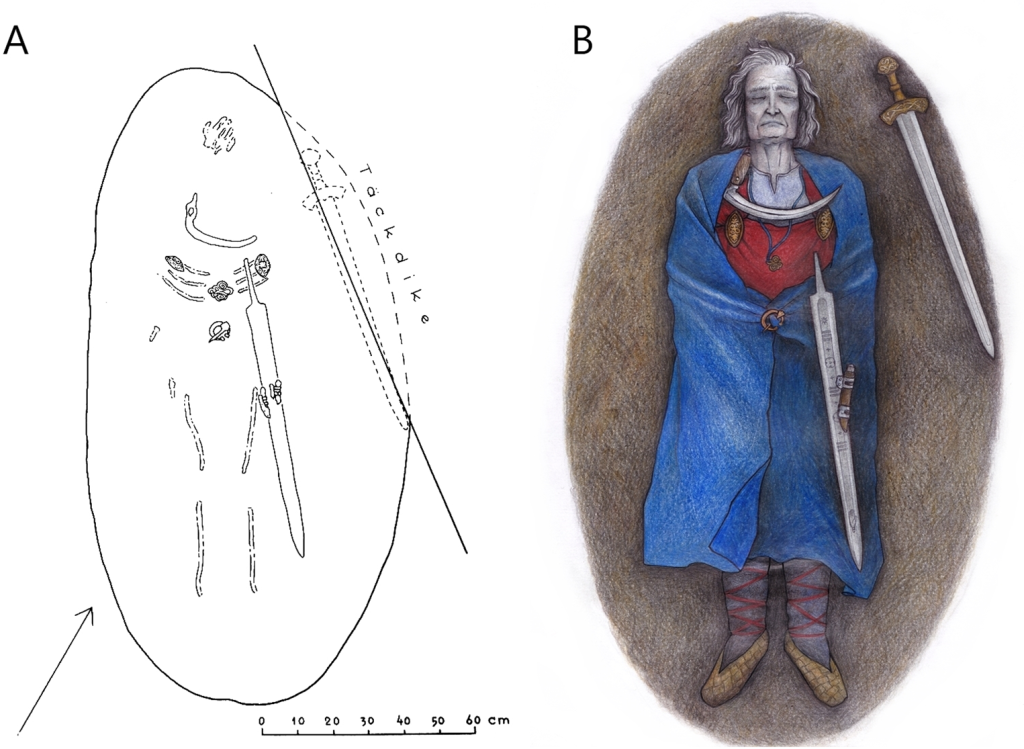

In 1968, a metal detectorist stumbled upon something unusual near the village of Suontaka in Hattula, Finland. Beneath the earth lay a burial site dated between 1040 and 1174 CE, containing the remains of an individual placed with care and intention. They were found with a sword beside them, and another, more elaborate weapon appeared to have been added later. Both swords were signs of status and strength, markers of respect rather than ordinary grave goods.

What made the discovery even more puzzling was what lay beside the swords. The person had been buried wearing clothing typical of medieval Finnish women, including ornate brooches and jewelry. At the time, scholars debated how to interpret the site. Some wondered if the grave had been mixed with another burial. Others questioned whether the individual was a woman who held an unusual role in their community, or perhaps a man buried with feminine items for reasons unknown.

For years, the story remained unresolved. The findings were noted in archaeological records but were often treated as an outlier, too unclear to fit into broader historical narratives.

That changed when researchers revisited the site with modern tools. Radiocarbon testing confirmed the timeline. More importantly, the context of the grave goods suggested that the burial had not been disturbed. The placement of the items was deliberate and not accidental. None of the swords, jewelry, and attire seemed out of place to the people who buried this person.

Rather than trying to explain the grave away, archaeologists began asking a different question. What if the person in the grave was not meant to be defined by a single category? And what if their community understood and honored that?

Science Meets History: Genetic Clues and the XXY Chromosome

For years, the Suontaka grave raised more questions than answers. The swords and jewelry suggested someone who lived a life outside the ordinary, but archaeologists could only speculate about the person’s identity. That changed when researchers from the University of Helsinki, the University of Turku, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology returned to the site with new tools and a deeper set of questions.

Using ancient DNA analysis, the team examined traces of genetic material preserved in the skeletal remains. The samples were fragile and incomplete, but what they found pointed to a rare chromosomal pattern known as Klinefelter syndrome. This condition, which affects about 1 in 650 male newborns, involves the presence of two X chromosomes and one Y chromosome instead of the typical XY configuration.

Klinefelter syndrome can present in a variety of ways. Some people may have physical traits such as reduced muscle mass, broader hips, less facial or body hair, or breast tissue development. Others may never realize they have it. The effects are diverse, and not all are visible or medically diagnosed. According to the National Institutes of Health, it is the most common sex chromosome disorder, but many cases go unnoticed throughout life.

This discovery brought new context to the burial. The individual may have had physical features that led them to be perceived in ways that did not align neatly with either male or female roles as defined by their community. Yet the grave was not hidden, corrected, or stripped of meaning. It was honored. The person was remembered with care, given both weapons and adornments, and later commemorated again when another sword was placed in the grave.

Still, the researchers caution against drawing quick conclusions. Elina Salmela, a geneticist from the University of Helsinki and co-author of the study, noted that while the DNA findings suggest the presence of Klinefelter syndrome, the results are based on limited genetic data due to the age and condition of the bones. The chromosomes tell part of the story, but identity is shaped by more than biology.

The significance of the Suontaka findings is not that they offer a definitive label, but that they invite a broader reading of the past. Moreover, it highlights the complexity and fluidity of gender roles in historical societies This was a person whose body and life may have stood apart from common norms, and whose community chose to honor them as they were.

Medieval Identities: Gender Roles Beyond the Binary

The Suontaka burial invites us to reconsider how medieval communities understood gender. In 11th to 12th century Finland, grave goods often followed clear patterns. Swords were typically buried with men, serving as symbols of strength, protection, and status. In contrast, jewelry and embroidered textiles often accompanied female burials. When archaeologists found both types of items in the same grave, carefully placed around one individual, they had to ask a different question. What did these choices say about how this person lived, and how they were seen?

The researchers who led the reexamination of the Suontaka site found no signs that the burial had been disturbed or blended with another. The arrangement appeared intentional. The clothing, the jewelry, and the swords were not contradictions but parts of one story. The people who buried this individual did not hide who they were. They honored them as they were.

This is not an isolated case. In 2017, researchers confirmed that the famous Viking warrior grave in Birka, Sweden belonged to a biologically female individual, despite the weapons, armor, and game pieces found at the site — all typical of a male warrior burial. That study helped reopen discussions about gender and status in early medieval Scandinavia (Hedenstierna-Jonson et al., 2017).

Findings like these challenge the idea that the gender binary has always defined how people lived or how they were honored in death. Some individuals may have embodied roles that did not fit neatly into male or female categories, and their communities may have made space for that complexity.

Still, scholars emphasize that we must interpret these graves with care. A 2020 article in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal warns that identifying non-binary individuals in prehistory involves more than identifying mixed grave goods or genetic anomalies. Without written records or self-descriptions, we cannot assume that these individuals saw themselves in the same terms used today. While archaeological evidence can suggest fluidity, applying modern gender categories risks misreading the cultural frameworks of the past.

What Archaeology Can and Can’t Tell Us

Archaeology helps us see how people were treated in life and in death. It shows us what societies valued, how they expressed status, and how they marked difference. In the case of the Suontaka grave, the material evidence points to a person who held significance in their community.

But archaeology cannot speak for the dead. It cannot confirm how someone understood themselves or how others named them. Without written records or firsthand accounts, researchers rely on context. This includes the symbolism of objects, burial patterns in the region, and comparisons with other sites. Even ancient DNA has limits. In the Suontaka study, the evidence for an XXY chromosome was strong but incomplete, based on degraded fragments.

Researchers acknowledge this uncertainty. Ulla Moilanen and her colleagues described the findings as suggestive, not definitive. Moilanen said, “The buried individual seems to have been a highly respected member of their community.” Furthermore, they emphasize that the physical manifestation of Klinefelter syndrome might have contributed to the individual not being viewed strictly within the binary gender framework. The care and respect accorded to their burial, evidenced by the prestigious grave goods, suggest that this person was not only accepted but valued and respected within their community. This respect challenges common misconceptions about rigid gender roles in historical contexts and highlights a possible understanding and acknowledgment of gender diversity in early medieval societies.

Responsible archaeology asks not only what the evidence shows, but what it can’t. It recognizes the need to interpret with care, especially when the subject is identity. As Ialongo and Pape (2023) explain, identifying a burial as non-binary based on grave goods alone risks reading modern ideas into a past that followed different rules. The Suontaka grave reveals a life that did not fit a narrow mold. But it also reminds us that respectful interpretation depends not only on science, but on restraint.

Why It Matters Today: Identity, Memory, and Representation

The Suontaka burial speaks to something larger than its time. It shows us that identity has always carried more depth than the categories we often try to place it in. Even in a period with no language for gender diversity as we understand it today, this person’s community buried them with care, not rejection.

Today, many people still face pressure to explain or defend who they are. Stories like this offer a way to reflect, not just on history, but on how we live now. They remind us that gender variance did not begin in the present. It has always existed, even if it was not always named.

When we recognize someone from the past who lived differently, we do more than revise a textbook. We challenge the idea that only certain kinds of lives deserve to be remembered. Honoring stories like Suontaka’s helps make space for more honest conversations about identity, belonging, and the quiet forms of respect that have shaped communities for centuries.

Featured Image from Ulla Moilanen, Tuija Kirkinen, Nelli-Johanna Saari, Adam B. Rohrlach, Johannes Krause, Päivi Onkamo, Elina Salmela under CC BY 4.0