Your cart is currently empty!

Sickle Cell Anemia Cure Reported in New York, a Major Medical First

For decades, sickle cell disease has meant living under the constant threat of pain crises that can strike without warning and derail school, work, and everyday plans. Now, doctors in New York are describing a turning point: a young adult treated with a one-time gene therapy has remained free of sickle cell symptoms, raising the possibility that “cure” is no longer just a long-term goal, but something starting to reach real patients. The breakthrough is promising, but it also comes with important questions about safety, follow-up, and who will be able to access a treatment this complex.

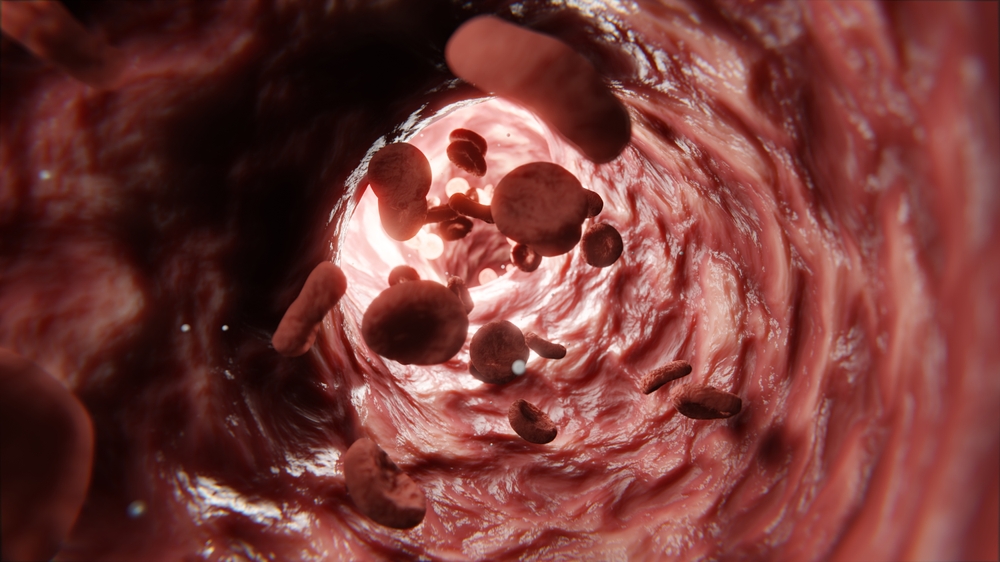

What Sickle Cell Disease Does to the Body

Sickle cell disease (SCD), sometimes called sickle cell anemia, is a group of inherited blood disorders caused by a mutation that affects hemoglobin, the protein red blood cells use to carry oxygen. In healthy blood, red blood cells are disc-shaped and flexible, able to glide through even narrow vessels. In SCD, many red blood cells become rigid and crescent-shaped, which makes them more likely to get stuck and block blood flow.

Those blockages can cause sudden, intense pain episodes often called vaso-occlusive crises or events. They can also reduce oxygen delivery to tissues, which is part of why the condition can affect many organs over time. Complications linked with SCD include chronic pain, stroke, lung problems, infections, kidney disease, and eye problems. The burden is not only physical; frequent crises can disrupt school, work, sleep, and relationships, especially when flare-ups arrive without warning.

SCD is lifelong, and for many years the main goal of treatment was to reduce symptoms and prevent complications through ongoing care and rapid response when crises occur. With consistent medical support, many people with SCD can still live fulfilling lives and take part in most activities, but the condition remains serious and unpredictable.

In the United States, SCD affects more than 100,000 people and is most common among non-Hispanic Black or African American individuals, while also affecting Hispanic or Latino communities.

Commonly cited estimates include about 1 in 365 Black babies born with SCD and about 1 in 13 Black babies born with sickle cell trait.

The First Reported Cure in New York and What Changed for One Patient

In New York, a milestone that once sounded distant is now being described in concrete terms by the clinicians involved. Northwell Health’s Cohen Children’s Medical Center says 21 year old Sebastien Beauzile became the first patient in New York to receive Lyfgenia, a one time gene therapy designed to treat sickle cell disease. The infusion took place on December 17, 2024, and the hospital reports he has remained free of sickle cell symptoms since then.

The shift matters because sickle cell disease is not just a diagnosis on paper. It can mean years shaped by sudden pain crises, interrupted routines, and repeated medical visits. Beauzile’s story, as described by local reporting, included chronic pain that disrupted everyday life. In a CBS New York segment, he framed the change in simple terms: “Sickle cell was like a blockade for me.”

Doctors involved in his care have described the moment as a real turning point, not simply a new medication. In the same report, Cohen Children’s physicians emphasized how quickly gene therapy is moving from research to real-world care. One clinician called it a case where “the future is here,” while another said the team felt “blessed” to be able to offer it.

It is still early in the broader history of these therapies, and long term follow-up remains essential. But for one New York patient, the outcome is being treated as proof that a curative approach is no longer theoretical, and that hospitals are beginning to deliver it outside of trials.

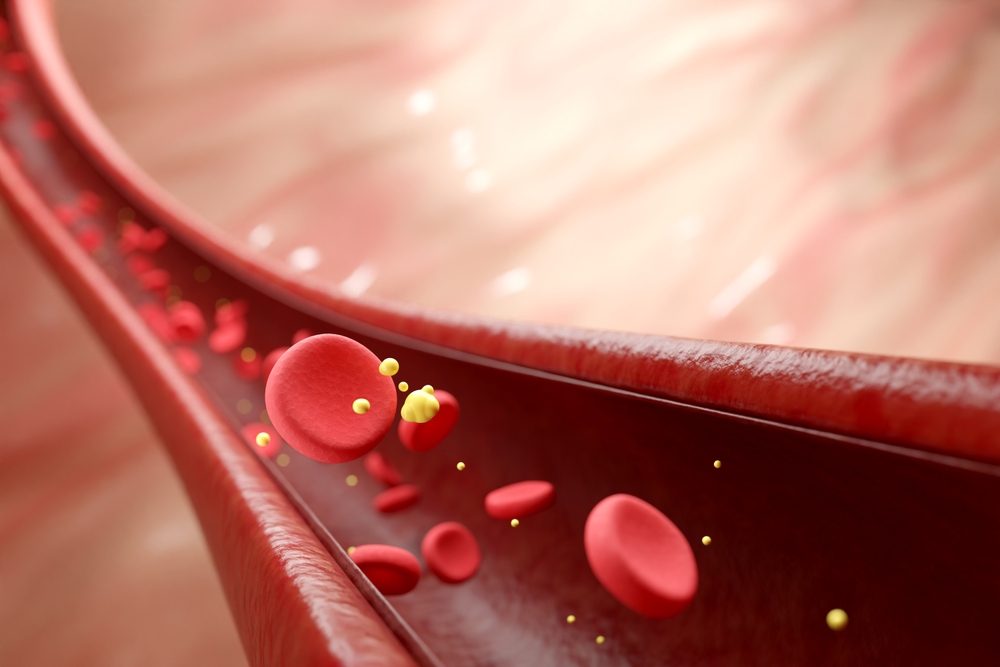

How Lyfgenia Works to Reduce Sickling and Restore Blood Flow

Lyfgenia is an autologous, stem cell based gene therapy. In plain terms, doctors use the patient’s own blood-forming stem cells, modify them, and return them to the body in a single infusion.

The process begins by collecting hematopoietic stem cells, the cells responsible for producing red blood cells. In the lab, those cells are genetically modified using a delivery system that adds instructions for making a therapeutic form of hemoglobin called HbAT87Q. This gene-therapy-derived hemoglobin is designed to function similarly to normal adult hemoglobin. Red blood cells containing it have a lower risk of sickling, which helps reduce the vessel blockages that drive pain crises and organ strain.

Before the modified cells are returned, patients undergo myeloablative conditioning, a high-dose chemotherapy regimen that clears space in the bone marrow. This step is crucial because it allows the modified stem cells to engraft, multiply, and take over blood production more effectively. After conditioning, the corrected cells are infused back into the patient as a one-time, single-dose treatment.

The goal is straightforward and practical: increase the share of red blood cells that resist sickling, improve blood flow, and reduce the likelihood of vaso-occlusive events that can cause severe pain and long-term complications.

What the Evidence Shows, and the Safety Questions That Still Matter

Lyfgenia and Casgevy represent a major shift in sickle cell care because they aim to prevent vaso-occlusive crises by changing how a patient’s blood is made. In December 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved both as the first cell-based gene therapies for sickle cell disease in patients ages 12 and older, with eligibility tied to a history of serious vaso-occlusive events or recurrent crises.

The approvals were based on ongoing single-arm clinical studies, meaning results were measured without a separate placebo comparison group. For Lyfgenia, effectiveness was evaluated by complete resolution of vaso-occlusive events between 6 and 18 months after infusion. In the pivotal study, 28 of 32 participants, or 88%, met that outcome. For Casgevy, the primary measure was freedom from severe vaso-occlusive crises for at least 12 consecutive months during a 24-month follow-up period. Among 31 participants with enough follow-up time, 29, or 93.5%, achieved it.

These numbers are encouraging, but they sit alongside important realities about risk. Because both therapies require myeloablative conditioning, many common side effects reflect high-dose chemotherapy and the underlying disease. Reported effects include low blood cell counts, mouth sores, nausea or vomiting, pain, abdominal discomfort, and fever associated with low white blood cell counts.

Lyfgenia also carries a serious warning: hematologic malignancy, a form of blood cancer, has occurred in some treated patients. For that reason, lifelong monitoring is recommended. The emerging picture is one of real progress with real tradeoffs, where outcomes can be transformative, but careful patient selection and long-term follow-up remain essential.

A Cure Changes the Story, but Access Will Decide Who Benefits

A first reported cure in New York signals a new era for sickle cell disease, but the impact will ultimately be measured by who can realistically receive it. Gene therapies like Lyfgenia and Casgevy offer the possibility of long-term freedom from vaso-occlusive crises, yet they also require intensive care, including high-dose chemotherapy and specialized transplant-level follow-up. For Lyfgenia, lifelong monitoring is part of the reality, not an afterthought.

Cost is another defining barrier. Lyfgenia has been priced at roughly $3.1 million per treatment, a figure that raises immediate questions about insurance coverage, out-of-pocket burden, and whether patients in under-resourced communities will be able to access the same breakthroughs as those treated at major centers. This concern lands especially hard in a disease that disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic families in the United States.

There is also a broader ethical point. A cure cannot be considered a true medical turning point if it remains rare in practice. That means expanding treatment centers, building referral pathways, and investing in patient support for travel, time off work, and long recovery periods. It also means pushing for transparent coverage policies that match the seriousness of the disease.

As pediatric hematologist Jeffrey Lipton put it, “This is a fix,” adding that while other drugs modify the disease, “this is a cure.” The call to action now is collective: health systems, insurers, policymakers, and communities all have a role in making sure a life-changing option does not become a luxury.