Your cart is currently empty!

We Found Oxygen Being Made in Total Darkness Without Plants

For centuries, the story of oxygen on Earth has seemed settled. Plants, algae, and certain bacteria capture sunlight, split water, and release oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. From school textbooks to university lectures, the message has been consistent: without sunlight, there is no natural production of oxygen. In the deepest parts of the ocean, far beyond the reach of light, life survives on what drifts down from above.

But in the inky darkness more than 13,000 feet below the Pacific Ocean’s surface, scientists have discovered something that challenges that long held belief. Oxygen appears to be forming in complete darkness, without plants and without sunlight. The phenomenon, now referred to as “dark oxygen,” could force a rethink of how life evolved on Earth and how we approach the growing push to mine the deep sea for battery metals.

The discovery is as humbling as it is exciting. It suggests that the deep ocean still holds processes we barely understand, even as industries prepare to industrialize its seafloor.

A Discovery in the Abyss

The finding comes from research led by Professor Andrew Sweetman of the Scottish Association for Marine Science. While studying the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, a vast stretch of seabed between Hawaii and Mexico, his team deployed benthic chamber landers nearly 4,000 meters below the surface. The expectation was straightforward. Deep-sea organisms consume oxygen. Over time, oxygen levels in the sealed chambers should drop.

Instead, something astonishing happened. Oxygen levels rose.

Across multiple deployments and cruises between 2021 and 2022, the chambers recorded oxygen concentrations increasing well beyond background levels. In some experiments, oxygen concentrations more than tripled over a 47 hour incubation period. Net oxygen production rates ranged between 1.7 and 18 millimoles of oxygen per square meter per day. These measurements were confirmed using both optode sensors and traditional Winkler titration methods.

The team worked systematically to rule out errors. They examined whether trapped air bubbles might have contaminated the samples. They evaluated whether oxygen could have diffused from plastic equipment. They tested whether injected fluids influenced the outcome. They even poisoned samples with mercury chloride to eliminate biological activity. Yet oxygen production persisted.

This left researchers with a radical conclusion. Oxygen was being generated on the abyssal seafloor by a non photosynthetic process.

The Role of Polymetallic Nodules

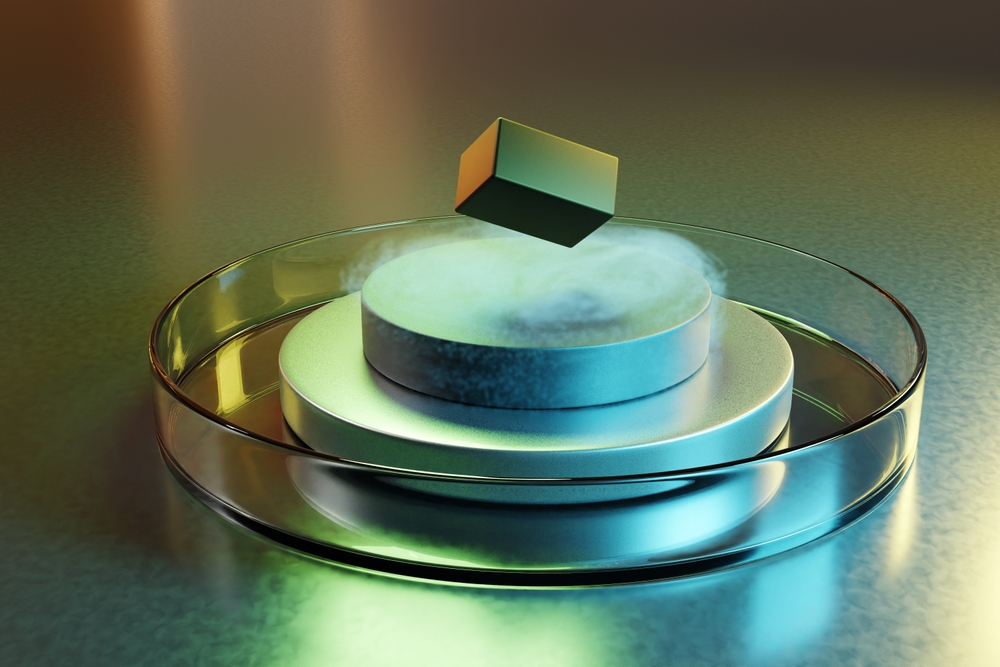

Scattered across the Clarion-Clipperton Zone are billions of potato sized rocks known as polymetallic nodules. These nodules form over millions of years as dissolved metals in seawater accumulate in layers around fragments of shell or debris. They contain manganese, nickel, cobalt, copper, and lithium, metals now central to electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy storage.

When researchers examined the nodules more closely, they discovered something remarkable. Measurements taken across 153 sites on 12 nodules revealed electrical potentials reaching up to 0.95 volts. Under certain conditions, that voltage approaches what is required to split seawater into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis.

Electrolysis requires an input voltage of about 1.23 volts, plus additional energy known as overpotential. However, certain catalytic materials can lower that requirement. The nodules contain manganese oxides enriched with transition metals such as nickel and copper, materials known to enhance conductivity and catalytic performance.

In laboratory experiments, the nodules behaved like natural batteries. When immersed in artificial seawater and connected with platinum electrodes, they produced measurable electric currents. When placed in contact with one another, they may function collectively, similar to batteries placed in series, increasing total voltage.

This led to what researchers describe as the geo battery hypothesis. The nodules may create localized electric currents that split seawater molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, producing oxygen without sunlight or biology.

If confirmed, this would represent a geological source of oxygen production in one of the most remote environments on Earth.

Rewriting the Origins of Oxygen

The implications extend far beyond marine chemistry. For decades, the dominant explanation for the rise of oxygen on Earth has centered on photosynthetic microbes emerging around 3.4 billion years ago. The Great Oxidation Event, which transformed Earth’s atmosphere, is tied directly to biological innovation powered by sunlight.

Dark oxygen complicates that story.

If oxygen can be generated through electrochemical reactions on mineral surfaces, then localized oxygen rich environments could have existed in the deep ocean long before photosynthesis reshaped the planet. These microenvironments might have supported early aerobic organisms, or at least prepared ecosystems to adapt once atmospheric oxygen increased.

Some researchers also see implications beyond Earth. If electrochemical oxygen production can occur in Earth’s oceans, similar processes might occur in subsurface oceans on icy moons such as Enceladus or Europa. Traditionally, the search for extraterrestrial life has focused on microbes relying on chemical energy gradients. But oxygen production independent of sunlight could expand the range of possible habitats for complex life.

Jeff Marlow, a co author of the study and assistant professor at Boston University, has suggested that this finding may broaden how scientists think about life in ocean worlds. Oxygen provides significant metabolic energy. If it can form without sunlight, larger organisms could theoretically survive in dark oceans elsewhere in the solar system.

Such possibilities remain speculative. But they illustrate how one unexpected signal from the seafloor can ripple across multiple scientific fields.

The Scientific Debate

As with any discovery that challenges established understanding, dark oxygen has drawn scrutiny.

Some critics have argued that the oxygen detected may have originated from trapped air bubbles within experimental equipment rather than from the seafloor itself. A preprint rebuttal led by scientists affiliated with The Metals Company suggested that contamination could explain the results and that the hypothesis of nodule driven oxygen production should be rejected.

Sweetman and his colleagues anticipated this skepticism. Their published research in Nature Geoscience details numerous control experiments designed to eliminate such explanations. The benthic chambers include one way valves to purge air during descent. Diffusion calculations indicate that oxygen from trapped air would equilibrate rapidly, not rise steadily over many hours. Plastic intrusion was calculated to account for only a small fraction of observed oxygen increases. Radiolysis and manganese oxide reduction reactions were modeled and found to explain less than half a percent of the oxygen produced.

Even so, the researchers themselves urge caution. Oxygen production was nonlinear and varied between experiments. It correlated with nodule surface area, suggesting spatial density matters. Upscaling these results to the entire region would be premature without additional studies.

Science advances through replication and refinement. Further expeditions planned for 2026 aim to use improved equipment to test the geo battery hypothesis more directly.

The Deep Sea Mining Dilemma

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is not only a site of scientific intrigue. It is also the focal point of an emerging deep sea mining industry. Polymetallic nodules are rich in the very metals required for electric vehicles and renewable energy infrastructure. Companies argue that harvesting these nodules could reduce reliance on terrestrial mining, which carries its own environmental and social costs.

Yet conservation groups and hundreds of marine scientists have called for a moratorium on deep sea mining. The discovery of dark oxygen adds another layer of uncertainty.

If nodules are indeed generating oxygen that supports abyssal ecosystems, removing or burying them could disrupt processes we barely understand. Oxygen is fundamental to respiration, nutrient cycling, and carbon processing. Sediment plumes generated by mining operations could smother nodules or alter their electrochemical properties.

Lisa Levin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography described dark oxygen as a new ecosystem function that must be considered when assessing mining impacts. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has warned that seabed mining could destroy life and habitat in mined areas.

At the same time, Sweetman himself has not framed his findings as an outright rejection of mining. Instead, he emphasizes the need for deeper understanding before large scale industrial activity proceeds. The tension reflects a broader climate challenge. The metals needed for decarbonization must come from somewhere. But solutions that address one environmental crisis cannot create another.

Life in the Dark

The deep sea is often described as Earth’s final frontier. Temperatures hover near freezing. Pressure crushes with the weight of thousands of meters of water. Sunlight never penetrates. Yet life persists, from microbes to strange invertebrates adapted to extreme conditions.

Oxygen availability shapes these ecosystems. In many abyssal regions, oxygen is supplied by slow moving global currents that transport surface waters downward over centuries. If localized oxygen production occurs on the seafloor, even intermittently, it could create microhabitats that support unique biological communities.

Researchers observed that dark oxygen production exceeded measured sediment community oxygen consumption in some experiments. That suggests the process could provide surplus oxygen for benthic respiration, at least temporarily. Whether it operates continuously or only under certain disturbances remains unknown.

Understanding this dynamic matters not only for conservation but for global biogeochemical cycles. The deep ocean plays a crucial role in carbon storage. Small shifts in oxygen levels can influence how carbon is processed and buried in sediments.

The fact that such a fundamental process may have gone unnoticed until now is a reminder of how little we truly know about the largest habitat on our planet.

A Cautious Turning Point

The discovery of dark oxygen does not overturn centuries of science overnight. Photosynthesis remains the dominant source of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere and oceans. But it opens a door to the possibility that geology, chemistry, and electricity may also contribute in ways previously unrecognized.

More importantly, it underscores the importance of humility. Industrial interest in the deep sea has accelerated rapidly in recent years, driven by climate goals and technological demand. Yet the ecosystems targeted for extraction remain poorly understood.

The debate surrounding dark oxygen reflects a broader environmental lesson. Scientific breakthroughs often complicate policy decisions rather than simplify them. They reveal hidden connections and unintended consequences.

If polymetallic nodules act as natural electrochemical reactors, quietly splitting water molecules in the darkness, then the deep sea is not merely a mineral deposit waiting to be harvested. It is an active, dynamic system with processes that may shape life in ways we are only beginning to grasp.

As researchers prepare the next generation of experiments, the world faces a choice. We can treat the deep ocean as a resource frontier, moving quickly to meet material demands. Or we can slow down long enough to understand the full implications of what lies beneath.

The discovery that oxygen can be made in total darkness without plants challenges more than textbooks. It challenges our assumptions about how life works, where it can exist, and how carefully we must tread when exploring Earth’s last unknown realms.