Your cart is currently empty!

A Kitchen Staple May Calm Autoimmune Inflammation, Scientists Say

For millions of people living with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, relief often comes at a steep price. Prescription medications can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars monthly, and many carry serious side effects. Yet researchers at Augusta University’s Medical College of Georgia have turned their attention to something far more humble, sitting in kitchen cabinets across America.

Baking soda, that familiar orange box used for everything from baking cookies to cleaning sinks, may hold unexpected promise for calming the destructive inflammation that characterizes autoimmune conditions. A study published in the Journal of Immunology presents some of the first scientific evidence explaining how sodium bicarbonate influences immune function at a cellular level.

Dr. Paul O’Connor, a renal physiologist in the MCG Department of Physiology, led the research team that made these observations. What began as an investigation into kidney disease treatment evolved into something with far broader implications for human health.

How Baking Soda Tells Your Spleen to Stand Down

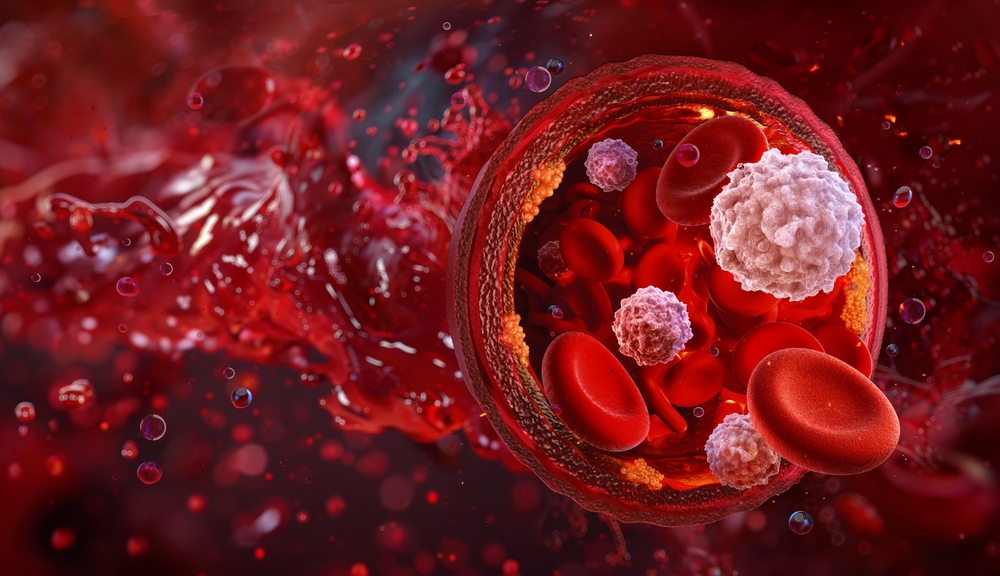

Understanding why baking soda affects inflammation requires a brief tour of human anatomy. Your spleen, roughly the size of a fist, functions as a major blood filter and storage facility for certain white blood cells called macrophages. As part of your immune system, it helps coordinate responses to potential threats.

When you drink a solution of baking soda dissolved in water, your stomach responds by producing more acid to prepare for your next meal. But something else happens, too. Specialized cells coating the exterior of your spleen pick up on chemical signals and essentially tell the organ to relax its defensive posture.

O’Connor described the signal in simple terms. “It’s most likely a hamburger not a bacterial infection,” is how he characterized the message these cells send to the spleen.

In other words, baking soda consumption triggers a cascade of communication that convinces your immune system that food is coming rather than foreign invaders. Your body responds by dialing back inflammatory activity rather than ramping it up.

Mesothelial Cells Act as Immune Messengers

At the heart of this discovery lies a type of cell that scientists only began to fully appreciate about a decade ago. Mesothelial cells line your body cavities, including the area containing your digestive tract. They also cover the exterior surfaces of your organs, preventing them from rubbing against each other.

But these cells do far more than provide a protective coating. Tiny finger-like projections called microvilli extend from their surfaces, constantly sensing the surrounding environment. When they detect something amiss, they can warn the organs they cover that an immune response might be necessary.

What makes these cells even more interesting is their neuron-like behavior. While O’Connor is quick to clarify that mesothelial cells are not actual neurons, they share certain characteristics with nerve cells. Most notably, they communicate using acetylcholine, a chemical messenger typically associated with the nervous system.

Researchers found that thin collagenous connections lined by mesothelial cells extend to the spleen’s outer covering. Through these delicate structures, chemical signals travel and influence how aggressively the immune system responds to perceived threats.

Macrophages Shift from Attack Mode to Calm Mode

Your body contains different types of macrophages, and their balance can determine whether inflammation runs rampant or stays under control. M1 macrophages promote inflammation, rushing to sites of infection or injury and triggering immune cascades. M2 macrophages do the opposite, working to reduce inflammation and help tissues heal.

After two weeks of drinking water mixed with baking soda, both rats and healthy human volunteers showed a notable shift in their macrophage populations. M1 cells decreased while M2 cells increased. Researchers observed this pattern in the spleen, blood, and kidneys.

Beyond macrophages, the team also documented increases in regulatory T cells. These immune cells generally work to dampen immune responses and prevent your body from attacking its own tissues, a malfunction that defines autoimmune diseases.

In human subjects, the anti-inflammatory shift lasted at least four hours. Rats maintained the effect for three days. While these timeframes might seem brief, they suggest that regular consumption could sustain ongoing benefits.

Kidney Disease Research Sparked an Unexpected Discovery

O’Connor and his colleagues did not set out to study autoimmune disease. Their interest in baking soda grew from observations about kidney health. One of the kidneys’ many jobs involves balancing important compounds like acid, potassium, and sodium. When kidney function declines, blood can become dangerously acidic, raising risks for cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis.

Clinical trials had already established that daily baking soda consumption could reduce blood acidity and slow kidney disease progression. Medical professionals now offer it as a standard therapy for certain kidney patients. But no one fully understood why it worked so well.

O’Connor’s team began investigating the mechanism behind these benefits. As they examined rat models with hypertension and chronic kidney disease, they noticed something unexpected. Animals consuming baking soda showed reduced numbers of inflammatory M1 macrophages and increased populations of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages.

Could this shift explain some of the clinical benefits patients experienced? And if so, might the same effect prove useful for other inflammatory conditions?

Evidence from Both Rats and Healthy Humans

Good scientists test their hypotheses in multiple ways before concluding. After observing the macrophage shift in diseased rats, O’Connor’s team examined rats without kidney damage. These healthy animals showed the same anti-inflammatory response when given baking soda.

Next came human trials. Working with colleagues at MCG’s Georgia Prevention Institute, the researchers recruited healthy medical students. Each participant drank baking soda dissolved in water, and blood tests tracked their immune cell populations over time.

Results mirrored what they had seen in animal models. “The shift from inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory profile is happening everywhere,” O’Connor reported. “We saw it in the kidneys, we saw it in the spleen, now we see it in the peripheral blood.”

Two mechanisms likely drive this effect. Some existing proinflammatory cells appear to convert to anti-inflammatory types. Simultaneously, the body seems to produce more anti-inflammatory macrophages from scratch. Combined, these processes create a measurable shift in immune function.

Fragile Connections Control the Immune Response

Perhaps the most surprising finding involved how easily the anti-inflammatory effect could be disrupted. Remember those delicate mesothelial connections linking to the spleen? Researchers discovered that even a slight physical disturbance broke them and eliminated the beneficial response.

When scientists removed the spleen entirely, the anti-inflammatory effect disappeared as expected. But even just moving the organ slightly, as might occur during abdominal surgery, was enough to break the fragile mesothelial connections and halt the response.

Examination under microscopy revealed visible changes. Spleen surfaces that appeared smooth before manipulation became lumpy and discolored after being touched. Whatever protective system baking soda activates clearly depends on these physical structures remaining intact.

Interestingly, cutting the vagal nerve had no such effect. Scientists had wondered whether signals traveled through this major cranial nerve, which connects the brain to the heart, lungs, and gut. But severing it did not disrupt the mesothelial cells’ behavior. Whatever communication occurs happens through more local pathways.

Comparing Baking Soda to Vagal Nerve Stimulation

O’Connor’s research intersects with another line of scientific inquiry. At institutions like the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, scientists have experimented with electrically stimulating the vagal nerve to reduce inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients. A 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported that this approach reduced both inflammation and disease severity.

No one has found a direct connection between the vagal nerve and the spleen, despite repeated searching by O’Connor’s team and others. Yet vagal stimulation still produces anti-inflammatory effects. Both approaches may tap into the same underlying system through different entry points.

Electrical nerve stimulation requires medical procedures and specialized equipment. Baking soda costs pennies and sits on grocery store shelves. If both methods produce similar outcomes, the implications for patient accessibility would be substantial.

A Safe and Affordable Option for Autoimmune Care

O’Connor remains cautiously optimistic about translating these findings into clinical applications for autoimmune patients. “You are not really turning anything off or on, you are just pushing it toward one side by giving an anti-inflammatory stimulus,” he explained when describing how baking soda works.

Rather than blocking specific immune pathways like many medications do, baking soda appears to nudge the entire system toward a calmer state. Such gentle modulation might prove safer for long-term use than more aggressive interventions.

Cost presents another consideration. Autoimmune disease treatments often run thousands of dollars annually. Generic baking soda costs almost nothing. For patients struggling to afford medications, an accessible alternative could prove meaningful.

Researchers also noted that spleen size increased in subjects consuming baking soda, likely because of the anti-inflammatory stimulus it produces. Physicians routinely check spleen size when evaluating patients for serious infections, since fighting off invaders can cause the organ to swell. Here, enlargement seemed to reflect increased anti-inflammatory activity rather than disease.

National Institutes of Health funding supported this research, signaling that federal health agencies see promise in this line of investigation.

What Remains Unknown and What Comes Next

Before anyone rushes to treat their rheumatoid arthritis with kitchen remedies, important caveats deserve attention. O’Connor’s study established mechanisms and demonstrated effects in healthy subjects and rat models. It did not test whether baking soda actually improves symptoms in people with autoimmune diseases.

Clinical trials specifically designed for autoimmune patients would need to determine appropriate dosing, duration of treatment, and whether the observed cellular changes translate into real symptom relief. Long-term safety studies would also be necessary, since regularly altering blood pH could theoretically create its own problems.

Questions remain about individual variation as well. Not everyone’s immune system behaves identically, and some patients might respond better than others. Researchers would need to identify who stands to benefit most from this approach.

Still, the elegance of the underlying science offers reasons for hope. A cheap, accessible compound that gently encourages the immune system toward anti-inflammatory behavior could complement existing treatments or help patients who cannot tolerate standard medications.

For now, the baking soda box in your pantry remains just an antacid and a leavening agent. But science has a way of finding remarkable properties in ordinary substances. What emerges from ongoing research may one day change how we think about managing inflammation and autoimmune disease.