Your cart is currently empty!

An Ancient Number Sequence Helped Solve One of Quantum Computing’s Biggest Problems

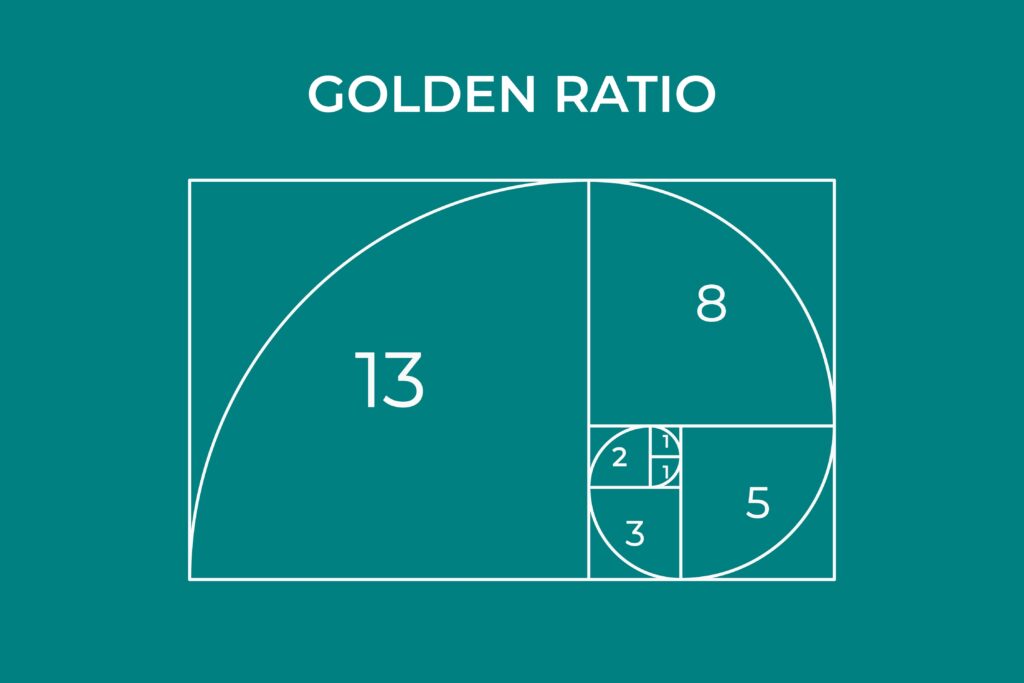

Leonardo of Pisa had no idea what he started. Back in the early 1200s, the Italian mathematician introduced a simple number sequence to the Western world. Each number in his sequence equals the sum of the two preceding numbers. Start with 0 and 1, and you get 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and onward forever.

For centuries, people found these numbers hiding in plain sight. Sunflower seeds spiral according to Fibonacci numbers. Seashells curve along Fibonacci patterns. Tree branches split in Fibonacci ratios. Artists and architects have used these proportions to create works that feel balanced and beautiful to human eyes.

But nobody expected Fibonacci’s 800-year-old pattern to solve a problem that has frustrated physicists for decades. Nobody expected it to change how we think about time itself. And certainly nobody expected it to create something that had never existed before in the history of the universe.

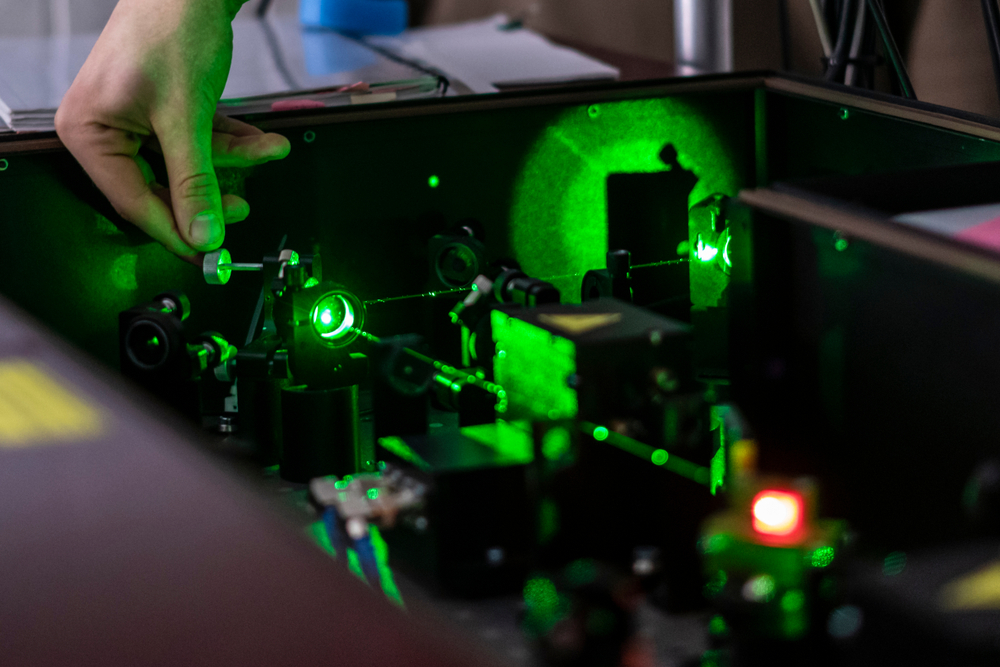

Yet that is exactly what happened when a team of researchers pointed lasers at a quantum computer and started pulsing them to the rhythm of Fibonacci numbers.

Numbers That Never Repeat

Before diving into the experiment, understanding what makes Fibonacci numbers special helps explain why they worked so well. Most patterns either repeat or dissolve into randomness. A clock ticks at regular intervals. Static noise follows no pattern at all.

Fibonacci numbers do something different. Each step depends on what came before, creating order. But the sequence never settles into a loop, preventing repetition. Mathematicians describe patterns like these as “quasi-periodic,” meaning they have structure without ever cycling back to the beginning.

Nature seems to love quasi-periodic patterns. Plants use Fibonacci spirals to maximize sunlight exposure. Pinecones and pineapples display these numbers in their scales. Even hurricanes sometimes show Fibonacci-like curves in their spiral arms.

Physicists noticed something interesting about these patterns. Systems built on quasi-periodic rhythms often prove more resilient than those built on strict repetition. They wondered if this same principle might apply to one of modern science’s most fragile and frustrating inventions.

Quantum Computing’s Frustrating Fragility

Quantum computers promise to solve problems that would take ordinary computers millions of years. They could design new medicines by simulating molecular interactions. They could crack codes that protect the world’s most sensitive information. They could optimize supply chains across entire continents.

All of these promises rest on a single word that sounds simple but represents one of physics’ greatest challenges: stability.

Ordinary computers store information as bits, tiny switches set to either 0 or 1. Quantum computers use qubits, which can exist as 0, 1, or both at the same time. Picture a coin spinning in the air rather than lying flat. While spinning, the coin is neither heads nor tails but some mixture of both possibilities.

Qubits are like that spinning coin, except far more sensitive. Heat disturbs them. Vibrations disturb them. Electromagnetic fields disturb them. Even looking at them wrong disturbs them. When a disturbance happens, the qubit collapses from its spinning state into a flat 0 or 1, and all the quantum magic disappears.

Philipp Dumitrescu, a quantum physicist who led the recent experiment’s theoretical work, described the problem plainly. “Even if you keep all the atoms under tight control, they can lose their quantumness by talking to their environment, heating up or interacting with things in ways you didn’t plan,” he explained. “In practice, experimental devices have many sources of error that can degrade coherence after just a few laser pulses.”

Most quantum systems lose their special properties in fractions of a second. Engineers have spent years trying to extend that window, shielding qubits from interference and developing error-correction schemes. Progress has been slow and painful.

Then someone asked a strange question. What if the solution had been sitting in a medieval math book all along?

Ten Atoms in Colorado

Quantinuum operates a quantum computer in Broomfield, Colorado, that uses ytterbium ions as qubits. For the experiment, researchers arranged ten of these ions in a straight line, each one trapped and controlled by electric fields. Laser pulses could manipulate the ions, changing their quantum states and creating entanglement between them.

Dumitrescu had been working with collaborators at the University of British Columbia, University of Massachusetts Amherst, and University of Texas at Austin on a theory. They believed that hitting qubits with laser pulses timed to Fibonacci numbers might protect quantum information in a new way.

Standard approaches use periodic pulses, alternating in a steady A-B-A-B pattern like a metronome. Dumitrescu’s team proposed something different. Instead of steady alternation, they suggested firing lasers in Fibonacci patterns. First A, then AB, then ABA, then ABAAB, and so on, with each segment building from the two segments before it.

On paper, the math looked promising. In reality, quantum computers are messy, complicated machines where theory often breaks down. Nobody knew if the approach would actually work until someone tried it.

Brian Neyenhuis led the experimental team at Quantinuum that put the theory to the test. They ran two versions of the experiment. In one, they pulsed lasers at the qubits in a standard periodic pattern. In the other, they used the Fibonacci-based sequence.

Results from the periodic approach showed the edge qubits maintaining their quantum states for about 1.5 seconds. Respectable by quantum computing standards, but nothing revolutionary.

Results from the Fibonacci approach showed something remarkable. Edge qubits stayed quantum for the entire 5.5 seconds of the experiment. They could have lasted longer, but the team stopped measuring at that point.

Nearly four times the stability. Same atoms. Same hardware. Different rhythm.

A Phase of Matter That Never Existed Before

What the researchers created went beyond just improved stability. They had produced something entirely new.

Matter exists in phases. Water can be solid ice, liquid water, or gaseous steam depending on temperature and pressure. Quantum materials have their own exotic phases, states of being where particles behave in strange collective ways.

Firing Fibonacci-patterned laser pulses at the qubits created what physicists call a temporal quasicrystal. Regular crystals, like salt or diamonds, have atoms arranged in patterns that repeat over and over through space. Quasicrystals have ordered arrangements that never repeat, like the famous Penrose tilings that can cover a floor with perfect structure but no repetition.

Temporal quasicrystals follow the same principle, except the non-repeating pattern unfolds through time rather than space. Each laser pulse relates to the pulses before it, creating structure. But the pattern never loops back to its starting point, preventing the kind of resonant errors that usually destroy quantum information.

Here is where things get strange. Quasicrystals in space are actually projections of higher-dimensional structures that have been squashed into fewer dimensions. A two-dimensional Penrose tiling, for example, is really a slice of a five-dimensional lattice. The Fibonacci-based temporal quasicrystal works the same way, except with time.

“What we realized is that by using quasi-periodic sequences based on the Fibonacci pattern, you can have the system behave as if there are two distinct directions of time,” Dumitrescu told reporters.

Two directions of time. Not in any mystical sense. Actual time still flows forward as it always has. But mathematically, the system’s behavior carries symmetries from an extra time dimension that does not physically exist. These bonus symmetries provide extra protection for quantum information, like a second lock on a door.

Why Extra Seconds Change Everything

A few seconds might not sound impressive. Human lives unfold over decades. Civilizations rise and fall over centuries. What difference could 5.5 seconds possibly make?

In quantum computing, those seconds represent an eternity. Current quantum processors struggle to maintain coherence long enough to complete even simple calculations. Every fraction of a second gained means more operations completed before errors creep in.

Justin Bohnet, a quantum engineer at Quantinuum who worked on the experiment, summarized why the results matter. “The key result in my mind was showing the difference between these two different ways to engineer these quantum states and how one was better at protecting it from errors than the other,” he said.

If researchers can scale the Fibonacci approach to larger systems, quantum computers might finally become practical tools. Drug companies could simulate how potential medicines interact with proteins. Climate scientists could model atmospheric systems with unprecedented accuracy. Cryptographers could develop new ways to secure information against future quantum attacks.

Each application depends on keeping qubits stable long enough to finish calculations. Without stability, quantum computers remain expensive laboratory curiosities rather than useful machines.

Structured Unpredictability

Beyond the practical benefits, the experiment suggests a philosophical shift in how scientists approach quantum control.

Traditional methods try to impose rigid order on quantum systems. Precise timing. Exact repetition. Complete predictability. Engineers have treated quantum computers like delicate clockwork, assuming that tighter control would yield better results.

Fibonacci pulses work differently. They provide guidance without repetition, structure without rigidity. Order emerges from unpredictability rather than fighting against it.

Dumitrescu described why this matters for protecting quantum information. “With this quasi-periodic sequence, there’s a complicated evolution that cancels out all the errors that live on the edge,” he explained. “Because of that, the edge stays quantum-mechanically coherent much, much longer than you’d expect.”

Nature has known this trick for billions of years. Biological systems thrive on patterns that balance order and variation. Hearts beat in rhythms that shift slightly from moment to moment. Brains fire neurons in patterns that hover between regularity and chaos. Perhaps quantum systems respond to similar principles.

Old Patterns, New Possibilities

Leonardo of Pisa introduced his sequence to help European merchants calculate compound interest and convert currencies. Eight centuries later, that same pattern might help humanity build machines capable of simulating the fundamental workings of reality.

Progress sometimes arrives not through adding complexity but through finding the right rhythm. Scientists struggling with quantum stability tried every sophisticated technique they could imagine. What worked was a number pattern that fits in a children’s math book.

As quantum technology continues to develop, Fibonacci numbers may prove to be more than mathematical curiosities. They may become a guiding principle for machines that push against the boundaries of what computation can achieve.

Sometimes the future hides in the past, waiting for someone to look at old ideas with new eyes.