Your cart is currently empty!

An Art Installation Let People Kill Goldfish and Revealed Something Dark

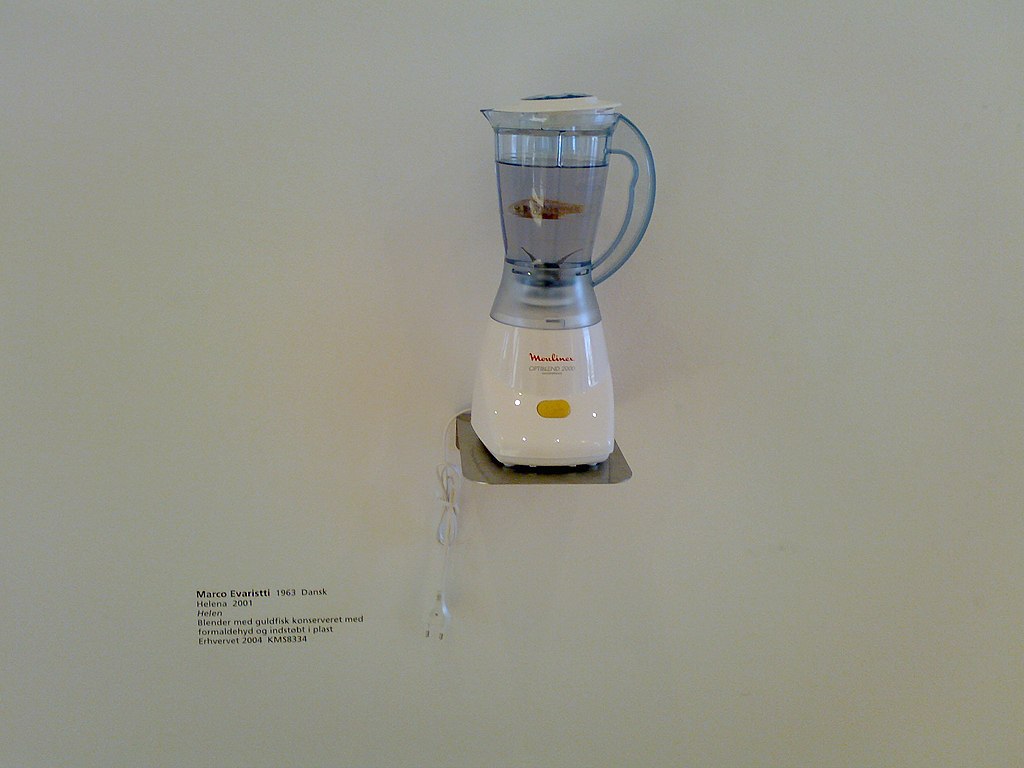

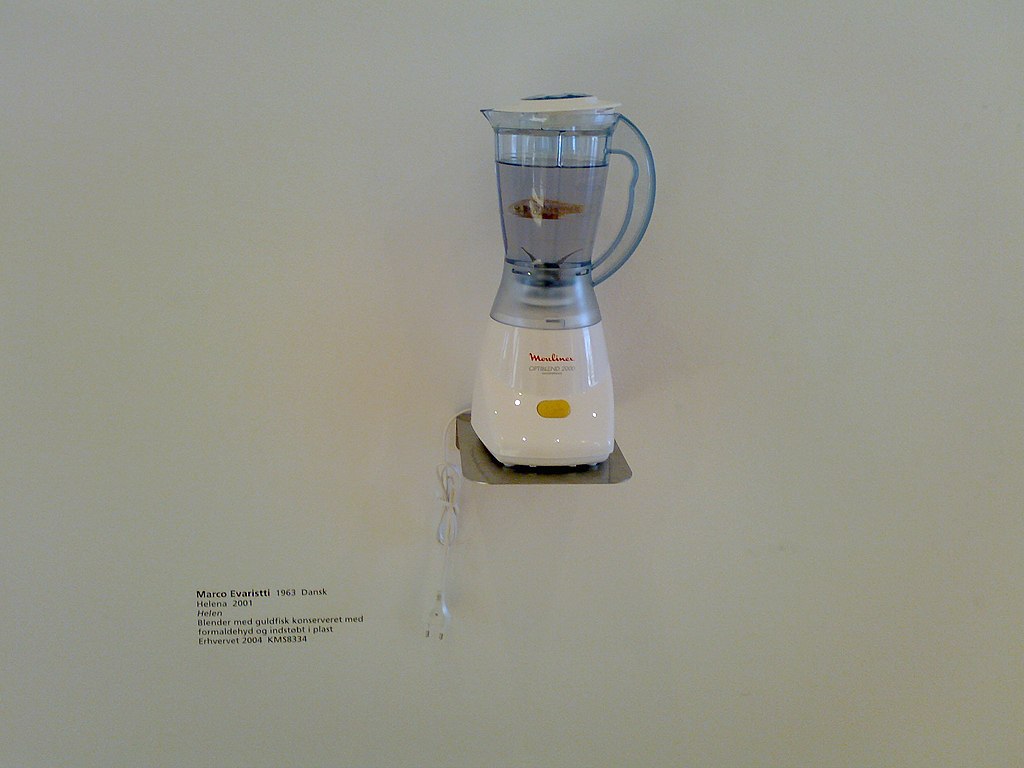

In 2000, an unusual art exhibit in Denmark forced museum goers to confront a chilling question: would you kill a goldfish for no reason other than because you could? The exhibit titled Helena & El Pascador by artist Marco Evaristti invited visitors to make a simple but morally fraught choice to press a button and activate a blender containing a live goldfish or walk away.

It may sound like a metaphor. It was not.

The blenders were real, the goldfish were alive and some people did press the button. What followed sparked public outrage, legal action and a lasting conversation about ethics, human psychology and the boundaries of artistic freedom.

The Installation That Asked Too Much

What made Helena & El Pascador especially controversial was not only its capacity for harm but the calculated simplicity of their design. The physical setup was sterile and domestic, with standard kitchen blenders lined up in a white gallery space. There was no dramatic lighting, no emotional soundtrack, no artist present to explain the intent in real time. The lack of framing meant the ethical burden shifted entirely to the observer who became both participant and potential perpetrator. That raw immediacy turned a passive viewing experience into a personal moral dilemma without mediation.

Evaristti stripped away abstraction and forced the visitor to acknowledge power in its most mundane form. The mechanism to kill was not complex or concealed but familiar and easily operated. As BBC News reported, the artist said the aim was to expose “the brutality that impregnates the world in which we live.” The installation’s brilliance, if one accepts that term, lay in how it made the act of violence feel as ordinary as flipping a kitchen switch. In doing so, it invited reflection not just on cruelty but on complicity and desensitization.

The exhibit also highlighted the psychological dynamic of public settings. Observers were not acting in isolation. The gallery environment made it clear that any action would be seen, yet no institutional or social guardrails stopped those who pressed the button. The silence from authority figures within the space added to the provocation. It was a scenario constructed not just to explore individual morality but to test the strength of collective restraint.

A Legal and Ethical Firestorm

The legal case that followed the exhibition drew widespread attention and exposed deep questions about where art ends and cruelty begins. After complaints from animal welfare groups, the police demanded that the gallery director at Trapholt Museum unplug the blenders. The director, Peter Meyer, refused on the grounds that cutting power would undermine the artistic statement. Police fined him 2000 kroner, but he refused to pay, prompting a trial. According to reporting at the time, the court acquitted Meyer because expert witnesses, including a veterinarian and a representative of the blender manufacturer, testified that the fish likely died almost instantly, which in their view did not amount to prolonged suffering under Danish animal welfare law.

Though the verdict cleared Meyer legally, it did little to calm public outrage. Many critics argued that legality did not address the moral dimension. An institution facilitating the voluntary killing of sentient creatures for any reason raises fundamental ethical concerns. Some animal rights advocates labelled the exhibit as gratuitous cruelty and said the court’s reasoning exposed gaps in legal protections for animals when art is involved. The case remains one of the most striking examples of how cultural expression and legal standards collide when living beings are involved.

The outcome sparked calls for clearer legislation and oversight regarding the use of live animals in art and public exhibitions. Observers and ethicists have used the case to argue that artistic freedom should not automatically override considerations of sentience and welfare. The legal acquittal for Meyer, while technically validating the exhibition under law, left an enduring question open. Just because an artwork can be defended in court does not mean it should be defended in conscience.

What the Experiment Revealed About Human Nature

The installation drew immediate comparisons to other infamous psychological experiments. One was psychologist Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment in 1971, which showed how quickly ordinary people could become cruel when given power. Another was artist Marina Abramović’s 1974 performance Rhythm 0, in which she allowed the public to use objects, including a loaded gun, on her body for six hours. That piece nearly ended in tragedy when an audience member pointed the gun at her head.

Evaristti’s exhibit tapped into similar psychological terrain. The central theme was not art for beauty’s sake but art as a moral provocation. What do people do when no one is stopping them and when the consequences are silent?

A study published in Frontiers in Psychology explored whether empathy is essential for moral behavior and found that while empathy can support prosocial action, it is not always a reliable driver of ethical decisions. Context, social norms and individual personality traits often play more significant roles. In the case of the goldfish exhibit, the absence of social barriers and the presence of perceived permission likely diminished empathetic responses and encouraged harmful behavior.

Artistic Freedom or Ethical Failure?

The debate around Helena & El Pascador remains relevant. Supporters believe the installation achieved its aim by provoking discomfort and reflection. It forced viewers to confront the moral consequences of their choices. Detractors argue that real harm crossed a line that art should not violate.

The broader discussion on ethical limits in art continues to attract attention from artists, philosophers and ethicists alike. Many argue that artistic intent does not grant blanket exemption from moral scrutiny, especially when the work directly inflicts or enables harm.

This tension remains unresolved. Unlike symbolic protest pieces, this exhibit involved actual risk and irreversible outcomes. Visitors were not merely reflecting on morality but participating in it. The use of live animals without oversight raised serious ethical concerns about institutional responsibility.

Public understanding of animal sentience has since evolved. Fish are increasingly recognized as beings capable of suffering and emotional response. This shift in perspective intensifies scrutiny of artworks that use living subjects as objects. Even brief exposure to harm for artistic effect raises serious questions about consent, dignity, and the limits of expression.

Evaristti later created other controversial works, including a dinner where guests ate meatballs made from his own liposuctioned fat. These pieces continued to push boundaries but none matched the visceral ethical challenge of the goldfish installation.

Its legacy lies in what it exposed. Some people, when left unchecked and invited to act without consequence, will choose harm. That truth demands ongoing reflection from artists, institutions, and audiences alike.

The Quiet Violence of Everyday Objects

What made Helena & El Pascador uniquely unsettling was not just its moral proposition but its use of a household appliance. The blender was not a weapon designed for violence. It was a familiar object from daily life recontextualized as an instrument of death. That shift turned an ordinary tool into a symbol of latent harm embedded in the mundane.

This framing invites deeper questions about how often cruelty and indifference are mediated through everyday technologies. From factory-farmed meat processed with industrial machinery to algorithmic systems that reinforce social inequalities, tools of harm often appear neutral. The more familiar the device, the easier it becomes to overlook its consequences.

The exhibit did not rely on graphic imagery or overt coercion. Instead, it leveraged the disarming normalcy of the blender to prompt viewers to examine how ordinary conveniences can mask ethical costs. In doing so, it called attention to the moral distance created by tools that enable harm without direct confrontation.

What This Exhibit Asks of Us

This installation does not simply belong to a moment in time. It continues to speak because it exposes something persistent and uncomfortable about human nature. What happens when harm is stripped of consequence, when responsibility is diluted into silence and when morality is left entirely to personal discretion? The gallery became a mirror not only of individual choices but of collective indifference. It asked not just what one person might do but how society frames and enables that choice through design, silence, and permission.

Evaristti did not force anyone to act. He only offered a question and made the cost of answering visible. That is what makes the piece so hard to dismiss. It blurred the line between observer and participant and asked whether we are as ethical as we believe when the world stops watching. The answer was not given by the artist or by the institution but by those who touched the button. That answer lingers and it stains. The discomfort we feel does not come from the idea of art pushing boundaries but from the reality of people crossing them willingly.

We often imagine morality as something shaped by laws or social contracts. But sometimes it is tested in silence by nothing more than a switch, a screen or a suggestion. This exhibit leaves us with a haunting question. If the next moral test came in a different form behind a screen in a lab in a policy in an algorithm, would we recognize it? Would we stop it? Would we care? If this work teaches anything, it is that the true measure of our ethics is not in what we claim to value but in what we allow to happen when no one is keeping score.

Featured Image from malouette, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons