Your cart is currently empty!

The Antarctic Waterfall That Bleeds Red in the Coldest Place on Earth

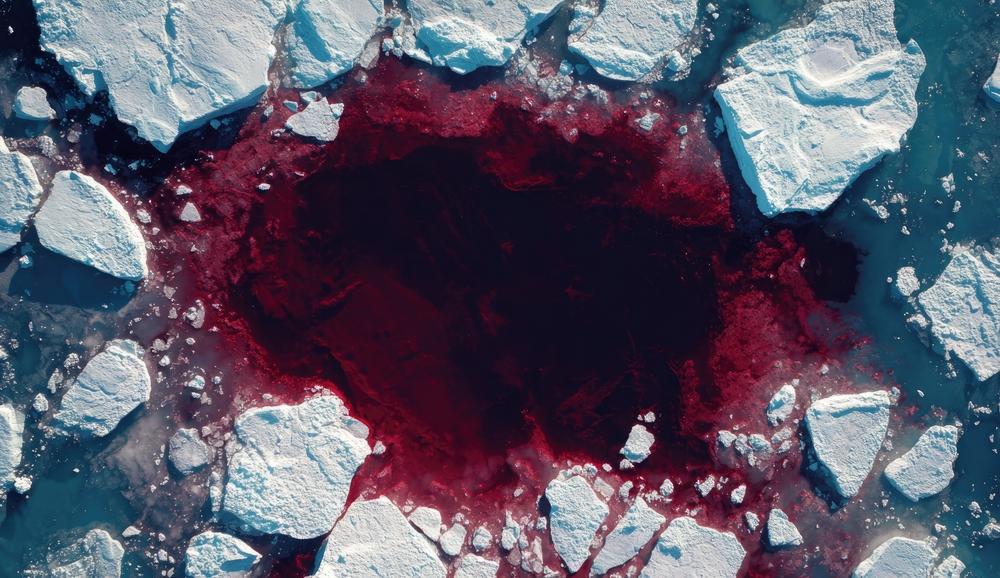

At first glance, it looks like something torn from a nightmare rather than a place on Earth.

In the middle of Antarctica’s frozen emptiness, a waterfall pours from a glacier in a deep, unsettling shade of red. It stains the ice below it, spreads across the snow, and slowly creeps toward a frozen lake. Against the blinding white landscape, the color is impossible to ignore. For more than a century, this eerie sight has sparked shock, confusion, and fascination in equal measure.

Known as Blood Falls, the phenomenon seems to defy everything people think they know about glaciers, water, and life in extreme environments. The waterfall flows in temperatures far below freezing. It appears blood red despite containing no blood. And beneath the ice that feeds it, scientists have discovered an isolated world that has been sealed off for millions of years.

What researchers have uncovered beneath this glacier has reshaped how we understand Antarctica, subglacial water systems, and the resilience of life itself.

A Waterfall in One of the Driest Places on Earth

Blood Falls is located in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, one of the strangest and most hostile regions on the planet. Despite being part of Antarctica, these valleys are classified as a polar desert. Snowfall is extremely rare, humidity is consistently low, and powerful katabatic winds race down from the polar plateau, stripping away moisture and preventing snow from settling.

The landscape looks more like Mars than the Antarctica most people imagine. Bare rock, frozen lakes, and dusty soils dominate the valleys, which remain ice free for much of the year. In this environment, the idea of a waterfall feels almost absurd.

Blood Falls emerges from the terminus of the Taylor Glacier, spilling slowly onto the ice and toward Lake Bonney below. At roughly five stories tall, it is not massive by global waterfall standards, but its setting makes it extraordinary. Glaciers are usually thought of as solid, immovable masses of ice. Seeing liquid water flowing from one in such brutal cold challenges long held assumptions about how glaciers behave.

Average temperatures in this region hover around minus 17 degrees Celsius, with winter temperatures plunging far lower. Under these conditions, freshwater would freeze solid almost instantly. Yet Blood Falls continues to appear, even during the darkest and coldest months of the Antarctic winter.

The Shocking Discovery in 1911

The first recorded sighting of Blood Falls occurred in 1911 during an expedition led by Australian geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor. While exploring what is now known as Taylor Valley, he encountered a vivid red stain spilling from the glacier’s face. The sight was so unexpected that it immediately stood out as one of the strangest discoveries of the journey.

At the time, Antarctica was still a place of profound mystery. Early explorers were mapping coastlines, identifying mountain ranges, and learning how to survive in an environment unlike any other on Earth. When Taylor documented Blood Falls, he had little context for what he was seeing.

Early theories attempted to explain the color using familiar biological explanations. Some scientists suggested red algae or microorganisms similar to those responsible for pink snow in other polar regions. These ideas persisted for decades, partly because the technology needed to probe deep beneath the glacier did not yet exist.

As a result, Blood Falls remained an enduring enigma. It appeared in photographs, expedition reports, and scientific discussions, but its true nature stayed hidden beneath hundreds of meters of ice.

Why the Water Looks Like Blood

Modern research has finally revealed that the waterfall’s color has nothing to do with blood or algae.

The red hue comes from iron.

Beneath the Taylor Glacier lies a reservoir of hypersaline water rich in dissolved iron. This brine has been trapped underground for millions of years, completely isolated from the atmosphere and sunlight. While buried beneath the ice, the water remains clear.

The transformation happens when the brine reaches the surface. As soon as the iron rich water comes into contact with oxygen in the air, it begins to oxidize. Oxidation is the same chemical process that causes metal to rust. As the iron reacts with oxygen, iron oxides form and turn the water a deep, rust red color.

The change is immediate and dramatic. What was once clear becomes vividly red, creating the illusion that the glacier itself is bleeding.

Recent studies suggest that oxidation may also create microscopic particles rich in iron, calcium, and magnesium. These particles scatter light in ways that intensify the color, making Blood Falls appear darker and more striking against the surrounding ice.

How Liquid Water Survives Extreme Cold

Perhaps the most puzzling aspect of Blood Falls is not its color, but its ability to remain liquid in such extreme cold.

The key lies in salt.

The subglacial water feeding Blood Falls is not freshwater. It is brine with a salt concentration far higher than seawater. Some measurements indicate it may be up to three times saltier than the ocean.

Salt dramatically lowers the freezing point of water. This principle is familiar to anyone who has seen salt spread on icy roads. In the case of Blood Falls, the extreme salinity allows the water to stay liquid at temperatures that would normally freeze water solid.

There is another process at work as well. When salty water begins to freeze, it releases latent heat. This heat slightly warms the surrounding ice, preventing complete freezing and helping maintain liquid channels beneath the glacier.

Advanced radar imaging has revealed that the Taylor Glacier contains a complex network of subglacial rivers, cracks, and pockets of brine. These hidden systems allow water to move slowly through the ice, sometimes for long periods, until it finds a pathway to the surface.

An Ancient Lake Trapped Under Ice

Scientists believe the water feeding Blood Falls originated millions of years ago, long before the modern Antarctic ice sheet took shape.

During periods when sea levels were significantly higher, parts of East Antarctica were flooded by ocean water. Taylor Valley and nearby regions may have functioned as fjords or inland seas connected to the ocean. When sea levels later fell and glaciers advanced, pockets of this salty water became trapped beneath advancing ice.

As ice formed above these pockets, salts were excluded from the freezing ice, making the remaining liquid even saltier. Over time, this process created an extremely concentrated brine sealed beneath hundreds of meters of ice.

The result is a subglacial reservoir that has remained isolated from the surface environment for at least one million years, and possibly much longer. This makes Blood Falls a rare geological time capsule, preserving chemical conditions from a distant past.

Life Without Sunlight or Oxygen

One of the most astonishing discoveries linked to Blood Falls has nothing to do with its appearance.

It has to do with life.

Deep beneath the glacier, in complete darkness and without oxygen, scientists have discovered living microorganisms. These microbes survive in conditions that were once thought to be completely incompatible with life.

Instead of relying on sunlight, these organisms use a process known as chemosynthesis. They obtain energy by breaking apart sulfate compounds in the brine. The byproducts of this reaction interact with iron in the water, allowing the sulfates to be regenerated and reused.

This recycling system has allowed microbial life to persist for millions of years in total isolation. The discovery has forced scientists to rethink the boundaries of where life can exist on Earth.

Why Scientists Are So Fascinated by Blood Falls

Blood Falls is more than a visual oddity. It provides rare insight into hidden systems operating beneath glaciers.

For decades, scientists assumed that glaciers in Antarctica’s coldest regions were frozen solid. Blood Falls has overturned that assumption. Even in extreme cold, liquid water can exist beneath ice, flowing through networks that remain invisible from the surface.

This understanding has major implications for glaciology. Subglacial water influences how glaciers move, how they erode bedrock, and how they respond to environmental changes. It also plays a role in transporting minerals and nutrients through otherwise frozen landscapes.

The Coldest Glacier Known to Host Flowing Water

Taylor Glacier holds a unique scientific distinction. It is considered the coldest known glacier on Earth that still supports a steady flow of liquid water.

This challenges long standing assumptions about the thermal limits of glaciers. It also raises new questions about how many other glaciers may conceal similar briny systems beneath their surfaces.

Researchers now suspect that subglacial brines may be more widespread in Antarctica than previously believed, quietly shaping the continent from below.

Studying Blood Falls Without Contaminating It

Conducting research at Blood Falls is extraordinarily difficult.

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are remote and harsh. Access typically requires helicopter transport from research stations, and every piece of equipment must be carefully cleaned to avoid contaminating the pristine environment.

Scientists rely on non invasive techniques such as radar imaging, seismic monitoring, and surface sampling. Drilling directly into the subglacial reservoir is avoided whenever possible to protect the fragile microbial ecosystem.

Each field season is limited by extreme weather, logistical constraints, and strict environmental regulations designed to preserve Antarctica for future research.

What Blood Falls Can Tell Us About Other Worlds

The significance of Blood Falls extends far beyond Earth.

The combination of salty liquid water, chemical energy, and life thriving without sunlight makes it a powerful analogue for environments elsewhere in the solar system. Icy moons like Europa and Enceladus are believed to harbor subsurface oceans beneath thick ice shells.

Mars also shows evidence of salty brines that may flow intermittently beneath its surface. Understanding how life survives beneath Taylor Glacier helps scientists refine their search for life beyond Earth.

A Mystery That is Not Fully Solved

Despite more than a century of study, Blood Falls continues to raise unanswered questions.

The waterfall does not flow continuously. Instead, it appears in pulses. Scientists are still uncertain what triggers each outflow. Some suspect pressure buildup within the subglacial reservoir, while others believe subtle shifts in the glacier open temporary pathways.

New technologies including improved radar systems and thermal sensors are helping scientists probe deeper into the ice. Each observation brings researchers closer to understanding this strange system.

A reminder of how little we know

Blood Falls stands as one of Antarctica’s most unsettling and fascinating natural wonders.

What appears to be a bleeding glacier is actually the result of ancient seawater, extreme chemistry, and resilient life working together beneath the ice. It challenges assumptions about where water can flow, where life can exist, and how dynamic Earth’s coldest environments truly are.

As scientists continue to study this blood red waterfall, Blood Falls remains a powerful reminder that even in the most remote corners of our planet, there are still mysteries waiting to be uncovered.