Your cart is currently empty!

Mysterious Object Falls on Argentine Farm From Sky

On a quiet evening in the small Argentine town of Puerto Tirol, an ordinary farmer named Ramón Ricardo González witnessed something that would make the evening news across the world. As dusk settled over the northern Chaco province, a loud thud echoed through his farmland. When González ventured out to investigate, he stumbled upon a bizarre, cylindrical object partially embedded in the soil, a massive metallic structure with fibrous material tangled around its edges, unlike anything he had ever seen. Measuring roughly 1.7 meters long and 1.2 meters wide, it looked at once artificial and otherworldly. Word spread fast through Puerto Tirol, drawing curious neighbors and speculation that ranged from alien technology to a fallen satellite.

Within hours, the police and local fire brigade had sealed off the area. Bomb disposal experts, dressed in protective gear, examined the strange device to ensure it posed no chemical or explosive risk. The metallic cylinder bore no obvious damage apart from slight charring, and the team quickly noticed a serial number etched into its surface, a key that would unlock its earthly origins. What initially seemed like the plot of a science fiction movie soon unfolded into a very real investigation into space debris and the growing dangers of a crowded orbit above our planet.

From Mystery to Mechanical Truth

Authorities from Chaco Police Headquarters confirmed days later that the object was not extraterrestrial in origin, but a component of a rocket fuel tank more precisely, a composite overwrapped pressure vessel (COPV). These high-tech containers are used to store gases at extremely high pressures aboard rockets. Engineers wrap them in advanced fibers, such as carbon or Kevlar, over a metallic core to keep them lightweight yet immensely strong. They’re part of the hidden machinery that allows rockets to function in space, carrying propellants or other essential fluids under conditions that would rupture almost any other material.

Experts quickly traced the object’s potential source. González’s farm sits directly beneath the flight path of a Chinese Jielong 3 rocket, launched from a sea vessel off the coast of China the previous day. Residents in several parts of Argentina reported seeing a bright, glowing object streaking across the sky that same night.

To the untrained eye, it looked like a meteor, but scientists now believe it was part of a controlled or semi-controlled reentry event, a piece of space equipment returning to Earth sooner than intended. The cylinder’s composition and size match previous reports of debris from similar rockets.

This wasn’t an isolated case. Just a month earlier, a nearly identical chunk of rocket debris was found in Western Australia’s desert. That object too appeared to be a COPV, the very same kind of component that fell in Argentina and experts noted it might have originated from another Jielong rocket. Space archaeologist Alice Gorman, speaking to ABC Radio Perth, explained that these fragments are part of a troubling pattern: modern rockets shed hardware that doesn’t fully disintegrate during atmospheric reentry. Some of it survives the fiery descent and lands wherever gravity dictates.

The Rise of Falling Space Junk

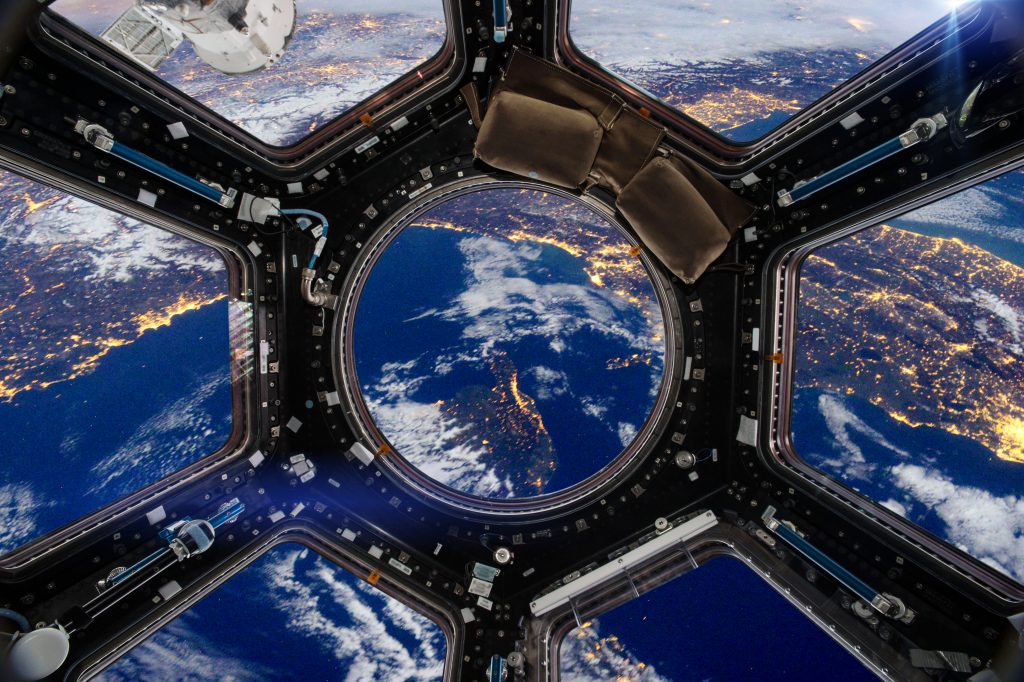

To understand how a farm in Argentina became an impromptu landing site for space machinery, one must look to the skies not for aliens, but for the growing cloud of human-made debris orbiting Earth. According to the European Space Agency (ESA), approximately 1,200 intact space objects re-entered Earth’s atmosphere in 2024 alone. Many of these were spent satellites, rocket stages, or fragments from collisions. ESA estimates that over 45,000 fragments larger than 10 centimeters currently orbit Earth, with millions more smaller than a marble, whizzing around the planet at speeds exceeding 27,000 kilometers per hour.

For decades, engineers assumed most space debris would burn up upon reentry. And indeed, most of it does; the atmosphere acts like a massive shield, vaporizing the majority of incoming material through intense heat and friction. But as space technology has evolved, so too have the materials used to build rockets. Composite materials like carbon fiber reinforced plastics are resilient, light, and heat-resistant qualities that make them excellent for space travel but troublesome for safe disposal. These components don’t always disintegrate as expected, meaning pieces can survive and impact the ground in remote or inhabited regions.

While no one has ever been killed by falling space debris, there have been close calls and minor injuries. In 2024, a small piece of discarded material from the International Space Station (ISS) tore through the roof of a home in Florida. The fragment, weighing less than a kilogram, had been jettisoned years earlier with other waste materials. Months later, a far larger piece weighing nearly 100 pounds from a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule smashed into a Canadian farm. Each incident reignited concerns about accountability in an age when launches are happening more frequently than ever before.

Argentina Joins a Growing List of Impacts

The discovery in Puerto Tirol now places Argentina alongside Australia, Canada, Mexico, and the United States, countries that have all recently found themselves on the receiving end of falling space debris. The similarity between these incidents is striking. In Mexico, a mysterious metallic orb landed in a tree near Veracruz in 2022, sparking wild speculation. Local meteorologist Isidro Cano described it as a metallic alloy sphere, marked with strange codes, and urged the public to avoid contact in case it was radioactive. Officials later removed the orb in a secretive nighttime operation, fueling conspiracy theories. The most plausible explanation? Another piece of jettisoned rocket hardware.

In Australia, miners discovered a smoldering piece of rocket fuselage on a desert road still warm to the touch, carbon-fiber blackened from its descent. In each case, the recovered materials bore the hallmarks of advanced aerospace engineering: lightweight composite construction, specialized coatings, and structural designs optimized for high-pressure environments. And in each case, there was evidence pointing to China’s rapidly growing launch program.

China’s space ambitions have skyrocketed in recent years, with dozens of launches annually. But this expansion also means an increase in uncontrolled reentries. The Jielong (Smart Dragon) rockets are small, commercial launchers designed to carry payloads into low Earth orbit. They are part of a booming global market that includes U.S., Indian, and European players. However, as more rockets ascend, more discarded boosters, tanks, and insulation panels fall back sometimes in spectacular fashion.

The Argentine incident highlights a critical gap in international space regulation. While there are guidelines under the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) for space debris mitigation, enforcement is largely voluntary. No global body monitors or penalizes countries for allowing parts of their spacecraft to reenter uncontrolled. The result is a patchwork of national responsibility that leaves individuals like González cleaning up the literal fallout of modern space exploration.

Space Archaeology and Accountability

Experts like Dr. Alice Gorman have coined the term space archaeology to describe the study of artifacts humans leave behind beyond our planet’s atmosphere. From defunct satellites to rocket boosters orbiting in silence, space archaeology seeks to document the evolution of humanity’s cosmic footprint. But now, that archaeology is returning to Earth in fields, deserts, and even homes.

Each piece of debris tells a story. The Argentine COPV offers insight into modern rocket engineering: how fiber-wrapped vessels withstand immense forces, how serial codes trace manufacturing origins, and how global launch networks connect seemingly distant events. But it also poses a serious question about stewardship. If human industry extends beyond Earth, who ensures its byproducts don’t pose risks back on the ground?

Under current international law, the country of launch bears liability for any damage caused by its space objects, even if the debris lands thousands of kilometers away. The 1972 Liability Convention covers such events, but enforcement is rare. Most nations prefer diplomatic solutions to financial claims, especially when debris causes no casualties. Still, as launches multiply, so too does the statistical likelihood of a catastrophic incident.

Experts have begun urging for new frameworks: global tracking databases, mandatory reentry controls, and shared accountability systems for commercial operators. After all, space is no longer a domain of superpowers alone. Private companies like SpaceX, Rocket Lab, and China’s Galactic Energy have made orbital launches routine and with each ascent, the potential for descent grows.

The New Normal of Falling Skies

The event in Argentina may soon be seen as a symbol of a new era: one where skyfall isn’t science fiction but a regular occurrence. As space traffic increases, the line between the cosmic and the terrestrial is blurring. It is now entirely plausible that every few days, somewhere on Earth, a piece of space debris is making its fiery return sometimes into the sea, sometimes into uninhabited land, and occasionally, into someone’s backyard.

The irony is that humanity’s quest to explore beyond our planet has made us more connected to it than ever. Each launch leaves behind a trail of invisible footprints, circling above until gravity reclaims them. For the people of Puerto Tirol, this connection became tangible the moment a metallic stranger fell from the sky. González, now something of a local celebrity, has kept a cautious distance from the object while scientists continue their analysis. He told local reporters he was both terrified and amazed, a feeling that neatly captures the dual nature of modern space exploration: awe wrapped in anxiety.

In the long run, the Argentine incident could help push space agencies and commercial operators to take debris management more seriously. Already, some companies are experimenting with self-deorbiting satellites, biodegradable components, and controlled reentry systems that guide debris safely into the ocean. But until such technologies become universal, stories like this will continue to emerge mysterious objects crashing down on ordinary people, reminders that space is not as distant as it once seemed.

A Message From the Sky

When González looked at the strange cylinder lying in his field, he was peering at the future one that humans have built piece by piece, launch by launch. The fallen object was not alien, but it was otherworldly in a deeper sense: it came from the edge of our technological ambition, from the machinery that carries our satellites, our experiments, and our dreams into orbit. That it landed on private land, thousands of miles from its origin, is both accident and omen.

Incidents like this remind us that our planetary boundaries extend far above the clouds. The sky is no longer an untouched wilderness. It has become a working corridor, crowded with the hardware of progress. And just as the oceans have taught us about pollution and responsibility, the atmosphere will teach us the same lessons in the years to come.

The next time a farmer looks up and sees a glowing object streaking across the night sky, it may not be a meteor. It may be a whisper from space a reminder that everything we send up must, eventually, come down.