Your cart is currently empty!

Astronomers Snap First-Ever Image of a Multi-Planet Solar System Beyond Ours

For decades, astronomers have searched the skies for planets beyond our own solar system, often relying on indirect evidence to confirm their existence. Now, for the first time, scientists have captured a direct image of multiple planets orbiting a star much like our Sun. The achievement, made possible with cutting-edge instruments at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, offers an unprecedented view of a planetary system still in its infancy, roughly 300 light-years away in the constellation Musca.

Unlike earlier discoveries that relied on observing a star’s subtle dimming or wobble, this breakthrough allows researchers to see a distant solar system in remarkable detail. The two massive gas giants revealed in the image open a new window into how planets form, evolve, and arrange themselves around their stars. Just as importantly, the discovery underscores how rapidly astronomy is advancing, bringing us closer to finding and perhaps one day directly imaging worlds more like our own.

A Breakthrough in Exoplanet Imaging

Astronomers have achieved a milestone in space exploration: capturing the first direct image of a solar system with multiple planets orbiting a star similar to our Sun. The star, known as TYC 8998-760-1, is located about 300 light-years away in the constellation Musca. While individual exoplanets have been imaged before, this is the first time scientists have managed to directly photograph more than one planet orbiting a sun-like star.

This breakthrough was made possible with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, operated by the European Southern Observatory. Using advanced instruments, researchers were able to block out the overwhelming glare of the host star, making the faint light of the planets visible. Both detected planets are massive gas giants, each much larger than Jupiter, and orbit at much greater distances from their star than Earth does from the Sun.

Direct imaging is particularly significant because most exoplanets are discovered indirectly by detecting the dimming of a star as a planet passes in front of it (the transit method) or by measuring a star’s wobble due to gravitational pull (radial velocity method). By contrast, direct imaging allows astronomers to actually see these distant worlds, providing unique insights into their atmospheric composition and formation history.

Credit:ESO/H. Heyer

What Makes This System Unique

The planetary system around TYC 8998-760-1 stands out not only because it resembles a younger version of our own solar system, but also due to its extreme scale. The two gas giants, named TYC 8998-760-1 b and TYC 8998-760-1 c, are estimated to be 14 and 6 times the mass of Jupiter, respectively. Unlike the relatively compact orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, these planets circle their star at far greater distances: one at about 160 astronomical units (AU) and the other at roughly 320 AU (one AU is the distance between Earth and the Sun). By comparison, Neptune, the farthest major planet in our solar system, orbits at only 30 AU.

This wide spacing provides scientists with an opportunity to study planetary systems that form and evolve differently from our own. Because these planets are so massive and so far from their star, they emit more infrared light, making them easier to detect despite their distance. Astronomer Alexander Bohn of Leiden University, who led the discovery, explained that the planets in this system orbit at far greater distances than those in our own solar system. This distinctive configuration could help refine models of how planetary systems form and why they take such varied shapes across the galaxy.

How Scientists Captured the Image

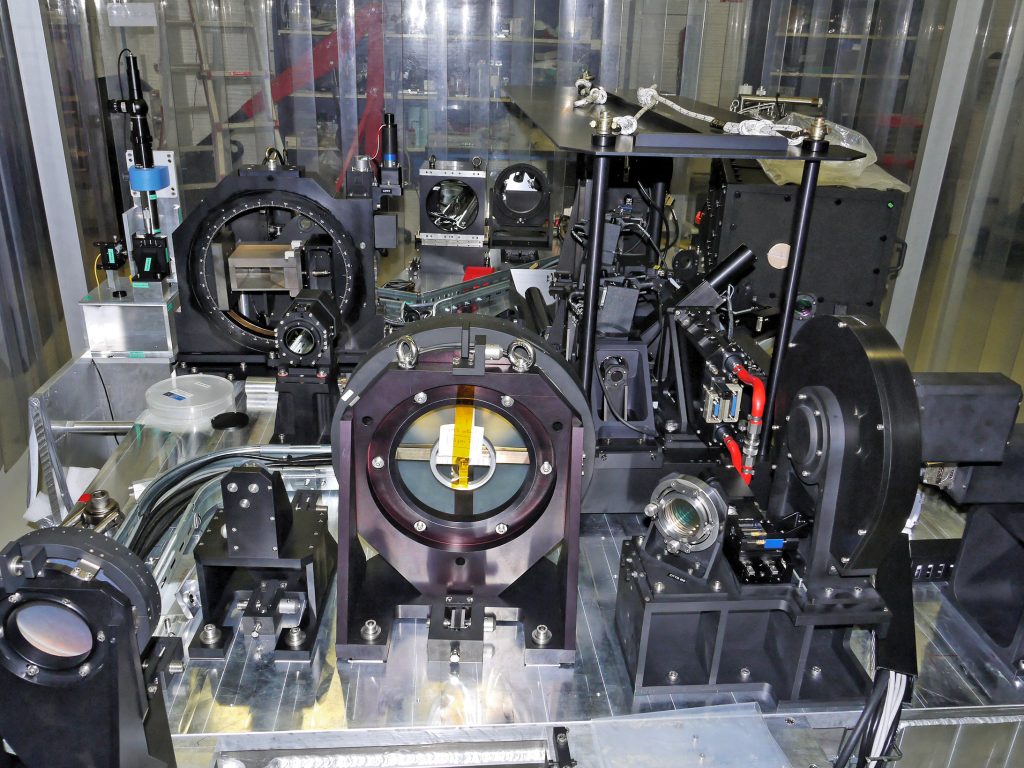

Photographing exoplanets is an immense challenge because a star’s brightness can outshine its planets by factors of millions or even billions. To overcome this, the team relied on the SPHERE instrument (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch) mounted on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. SPHERE is designed to block most of a star’s light using a device called a coronagraph, allowing the faint glow of orbiting planets to become visible.

Even with this technology, capturing such an image requires extraordinary precision. The light from these planets is not reflected sunlight but rather their own emitted heat, since they are still young, only about 17 million years old, and radiating residual warmth from their formation. By focusing on this infrared light, scientists were able to distinguish the planets from background stars and confirm that they are indeed gravitationally bound to TYC 8998-760-1.

This success highlights how far observational astronomy has advanced in the past two decades. Early exoplanet discoveries relied solely on indirect detection, but instruments like SPHERE now allow astronomers to directly observe worlds orbiting distant suns. Such direct imaging is crucial for future studies of exoplanetary atmospheres, compositions, and potentially even habitability in smaller, rocky planets around nearby stars.

Why This Discovery Matters

Directly imaging multiple planets around a Sun-like star is more than just a technical achievement. It reshapes how scientists understand planetary systems. By studying TYC 8998-760-1, astronomers gain a rare look at a system still in its formative stages, offering clues about how planets are born and migrate over time. The system’s extreme orbital distances, for example, challenge existing models that predict giant planets typically form closer to their host star before drifting outward.

The discovery also adds weight to the idea that solar systems like ours are not unique but may represent just one version of many possible planetary arrangements. According to the NASA Exoplanet Archive, more than 6000 exoplanets have been confirmed as of 2025, yet very few have been imaged directly. Most of these systems reveal surprising diversity: “hot Jupiters” orbiting scorchingly close to their stars, super-Earths larger than our planet but smaller than Neptune, and now, distant giants like those around TYC 8998-760-1.

Ultimately, milestones like this bring scientists closer to answering fundamental questions: How common are solar systems like ours? Could some of them harbor habitable worlds? While TYC 8998-760-1’s planets themselves are gas giants unlikely to support life, studying them helps refine techniques that could one day capture images of Earth-like planets orbiting in the habitable zones of nearby stars.

Looking Ahead: A New Window Into Distant Worlds

The first image of a Sun-like star with multiple planets offers a glimpse into the next chapter of astronomy. As instruments become more powerful, including upcoming projects like the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, the ability to capture smaller and fainter exoplanets will expand dramatically. These advancements could eventually allow scientists to detect rocky, Earth-sized planets and even probe their atmospheres for potential signs of life.

For the public, discoveries like this are reminders that our universe is far richer and more diverse than we can imagine. Each milestone in exoplanet research challenges us to see our solar system in context, not as the blueprint for all others, but as one story among billions. Supporting investment in space science and global collaboration in astronomy ensures that humanity continues uncovering these distant worlds and, perhaps one day, answers the timeless question: Are we alone?

Featured Image Credit: ESO/Bohn et al.