Your cart is currently empty!

How Falling Vaccination Rates Are Bringing Measles Back to the United States

For decades, measles was a word most Americans rarely heard outside of history books or old vaccination records. It was a disease many parents assumed no longer posed a real threat, something their grandparents worried about, not something that could shut down schools, overwhelm hospitals, or take children’s lives in 2025. That sense of safety is now unraveling.

Across the United States, measles cases are rising at a pace not seen in a quarter century. Outbreaks are spreading from state to state, quarantine orders are returning, and public health officials are warning that the country could soon lose its long held measles elimination status. While the virus itself has not changed, experts overwhelmingly agree on what has. Vaccination rates have fallen, misinformation has flourished, and trust in public health has eroded.

A West Texas Outbreak That Changed the National Conversation

In late January, health officials in Texas began tracking what initially appeared to be a small cluster of measles cases in West Texas. Within weeks, it became clear that this was not an isolated incident. The virus spread rapidly through largely unvaccinated communities, jumping from household to household and into schools.

By the time the Texas Department of State Health Services declared the outbreak over on August 18, the numbers were staggering. A total of 762 confirmed measles cases had been recorded since January. More than two thirds of those infected were children. Ninety nine people required hospitalization, and two school aged children died.

Jennifer A. Shuford, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said the outbreak was contained only after an intensive statewide response. That effort included expanded testing, emergency vaccination clinics, disease surveillance, and widespread public education campaigns. Many clinicians, she noted, were treating measles for the first time in their careers because the disease had been so rare for so long.

Public health officials consider a measles outbreak officially over after 42 consecutive days with no new cases. That period represents double the virus’s maximum incubation window, ensuring that hidden chains of transmission have ended. While Texas has stopped updating its outbreak dashboard, state officials continue monitoring for new cases, acknowledging that the threat has not disappeared.

Why Measles Spreads So Easily

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known to medicine. It spreads through direct contact with infectious droplets and through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or breathes. The virus can linger in the air of an enclosed space for up to two hours after an infected person has left.

Symptoms usually appear one to two weeks after exposure. Early signs often resemble a severe cold, including high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes. Several days later, a distinctive rash emerges, starting as flat red spots on the face before spreading down the neck and across the body.

People with measles are contagious for roughly four days before the rash appears and four days afterward. That window makes containment extremely difficult, especially in settings like schools, churches, and airports where close contact is common.

Health officials warn that measles is not a harmless childhood illness. During outbreaks, about one in five children who become infected require hospital care. One in twenty develops pneumonia. In rare cases, the virus can cause swelling of the brain, leading to permanent disability or death. Pregnant people face additional risks, including premature birth and low birth weight.

The Vaccine That Once Eliminated Measles

The measles mumps rubella vaccine, commonly known as MMR, is one of the most effective vaccines ever developed. Two doses prevent more than 97 percent of measles infections. Even in rare cases where vaccinated individuals do become infected, symptoms are typically milder and far less likely to spread to others.

Routine use of the MMR vaccine led the United States to achieve measles elimination status in 2000. That designation meant there had been no continuous spread of the virus for more than a year. For many Americans, it reinforced the belief that measles was no longer a serious domestic concern.

Current recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call for one dose of the MMR vaccine at 12 to 15 months of age and a second dose at 4 to 6 years. Each dose further reduces the risk of infection and severe illness. Children too young to be vaccinated rely on high community vaccination rates for protection.

Falling Vaccination Rates and Growing Vulnerability

Despite the vaccine’s proven effectiveness, vaccination rates across the United States have been declining for years. Researchers report that MMR coverage among kindergartners has dropped from around 95 percent before the pandemic to roughly 92 percent in recent school years. Among children vaccinated by age two, coverage now sits near 90.8 percent, nearly five percentage points below national targets.

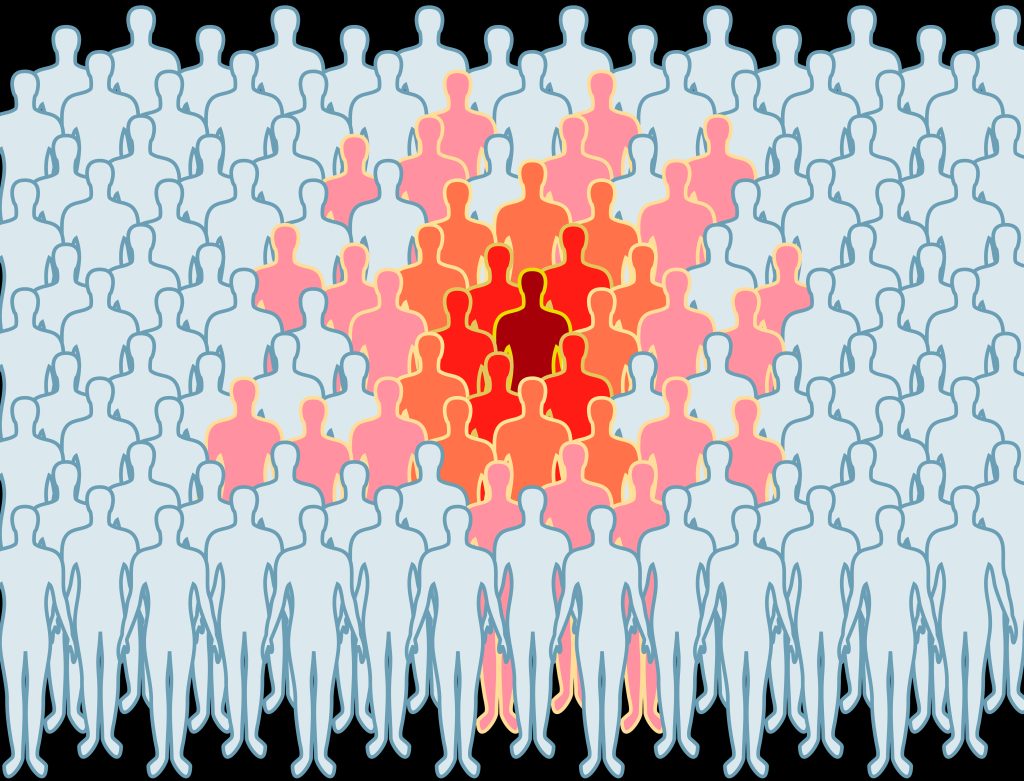

While those numbers may appear close, measles exploits even small gaps in immunity. Experts emphasize that the virus does not need a majority of people to be unprotected. It only needs pockets of low vaccination to spread rapidly.

This pattern was evident in West Texas. While Texas overall reports high vaccination rates, the outbreak’s epicenter included communities where exemption rates were significantly higher. In some counties, nearly one in five kindergartners had exemptions from at least one required vaccine.

The Role of Misinformation and Vaccine Hesitancy

Doctors and epidemiologists say the resurgence of measles is not a scientific failure but a social one. For years, false claims about vaccine safety have circulated online and through influential voices, eroding public confidence.

The anti vaccine movement gained traction well before the Covid pandemic, but experts say the pandemic intensified distrust and amplified misinformation. During the West Texas outbreak, inaccurate claims about the MMR vaccine spread widely, including debunked links to autism and misleading statements about vaccine ingredients.

Fiona Havers, a former infectious disease staffer at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and now an adjunct associate professor at Emory University, described the situation as a clear example of the damage caused by decades of false information. She noted that declining vaccination rates have made outbreaks harder to control and easier to ignite.

Public debate was further inflamed by mixed messaging from political figures. While Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. publicly endorsed the MMR vaccine in April, he had previously made statements questioning its effectiveness and promoting unproven treatments. Those remarks, experts say, added confusion during an already volatile moment.

Measles Spreads Beyond Texas

As Texas worked to contain its outbreak, measles cases were quietly multiplying elsewhere. Health authorities traced infections to major airports, schools, and religious gatherings, often linked to unvaccinated individuals.

South Carolina reported more than 120 cases this year after recording just one case in all of 2024. In Spartanburg County, hundreds of people were quarantined following exposures at schools and a local church. Arizona documented 176 cases, with nearly all occurring in unvaccinated people. Utah reported more than 100 cases, many connected to an outbreak that expanded through the summer.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the United States has recorded more than 1,900 confirmed measles cases this year, along with three deaths and 47 distinct outbreaks. Approximately 88 percent of cases are linked to outbreaks, underscoring how rapidly the virus spreads once it gains a foothold.

The Risk of Losing Elimination Status

A country loses measles elimination status after 12 months of uninterrupted transmission. Health officials warn that the clock is now uncomfortably close to expiring.

If outbreaks in states like South Carolina and Utah cannot be fully contained and traced back to the original West Texas cluster, the United States could officially lose its elimination designation. While the label itself may sound technical, experts say the consequences are real.

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, has warned that focusing solely on the designation misses the larger crisis. He described the situation as a house already on fire, arguing that waiting for formal milestones distracts from the urgent need to act.

A Global Problem With Local Consequences

The resurgence of measles is not limited to the United States. Canada has reported more than 5,100 cases since October 2024, with two infant deaths. That outbreak, which began at a wedding, spread across nine provinces, raising concerns that the Americas could collectively lose their elimination status.

Infectious disease specialists say global travel makes national borders irrelevant to measles. Ongoing outbreaks in North America and around the world increase the likelihood of imported cases, especially in areas where vaccination coverage is uneven.

What the End of the Texas Outbreak Really Means

The official end of the West Texas outbreak offers cautious reassurance but little comfort. It demonstrates that coordinated public health responses can still stop measles, even after months of intense spread. At the same time, it highlights how quickly progress can be undone.

Two children died from a disease that had been considered eliminated for an entire generation. Hospitals were strained, schools disrupted, and communities fractured by fear and misinformation.

Health officials emphasize that the absence of new cases does not mean the threat has passed. Providers are urged to remain vigilant, test patients with compatible symptoms, and report suspected cases immediately. People who believe they may have been exposed are advised to isolate and contact healthcare providers before seeking care, reducing the risk of further spread.

Trust, Prevention, and What Comes Next

Experts agree that measles did not return because vaccines stopped working. The virus did not mutate into something new. What changed was trust.

Rebuilding that trust will not be easy. It requires consistent messaging, transparent communication, and community level engagement that addresses fears without amplifying falsehoods. It also requires acknowledging the real consequences of declining vaccination, measured not in statistics alone but in hospital beds filled and lives lost.

Losing measles elimination status may seem abstract, but living with measles again is not. It means more quarantines, more preventable deaths, and a return to risks that modern medicine once pushed into the past.

The surge in measles cases is a warning. Whether it becomes a turning point or a footnote in a larger public health failure depends on what happens next, in clinics, classrooms, and living rooms across the country.