Your cart is currently empty!

Meet the Pencil-Tip Frog That Took Decades to Find

Something strange was happening in the misty mountain forests of southern Brazil. Researchers hiking through the Serra do Quiriri range kept hearing a distinct, high-pitched call echoing through the trees. Yet when they stopped to look, they found nothing. Whatever creature was making those sounds seemed to vanish into thin air.

For weeks, scientists followed these phantom calls through dense leaf litter, crouching low and moving slowly. What they eventually discovered was hiding in plain sight, though plain hardly describes it. Bright orange and impossibly small, a creature no bigger than a pencil eraser had been calling out from the forest floor all along.

Brazil’s Atlantic Forest had just revealed another secret. And what a secret it turned out to be.

A Frog That Fits on Your Fingernail

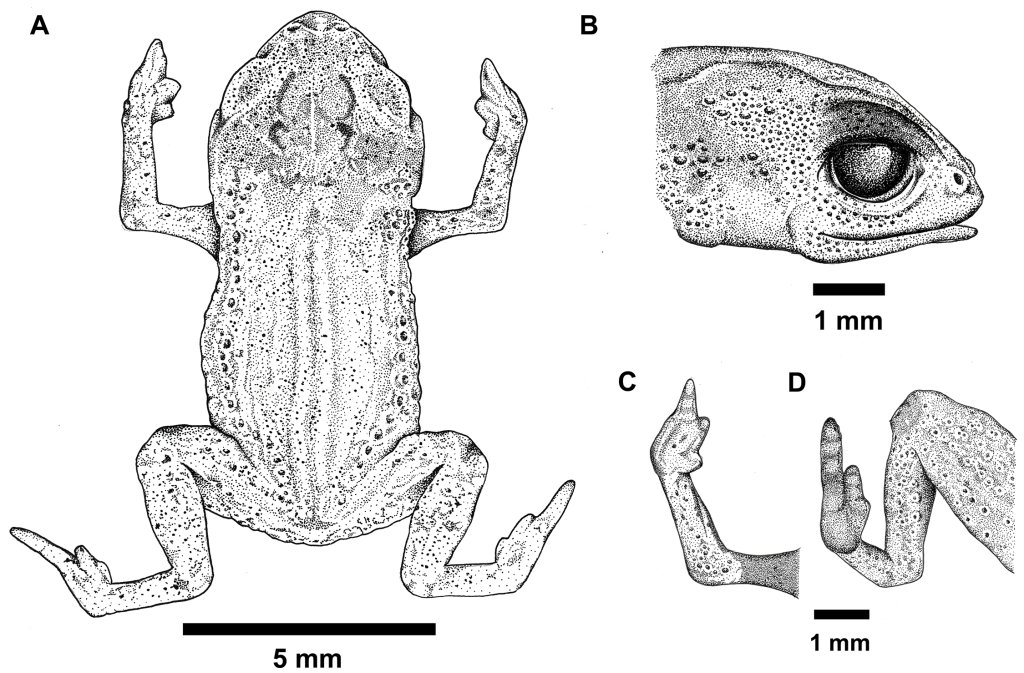

Researchers have now formally described Brachycephalus lulai, a new species of pumpkin toadlet found only in cloud forests along Brazil’s Serra do Quiriri mountain range. Males measure between 8.9 and 11.3 millimeters long. Females grow slightly larger, reaching up to 13.4 millimeters. For perspective, that means an adult could comfortably sit on the tip of a standard pencil with room to spare.

Bright orange coloration covers most of their tiny bodies, punctuated by small green and brown patches along the sides. Despite wearing what amounts to nature’s version of a high-visibility jacket, these frogs remain remarkably difficult to spot. Their miniature size and habit of hiding in leaf litter make visual detection nearly impossible.

Scientists named the new species after Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a decision meant to draw attention to conservation needs in the region. “Through this tribute, we seek to encourage the expansion of conservation initiatives focused on the Atlantic Forest as a whole, and on Brazil’s highly endemic miniaturized frogs in particular,” researchers wrote in their study, published in PLOS One.

Heard But Not Seen

Finding B. lulai required patience and a good ear. Male pumpkin toadlets produce advertising calls to attract mates, and these vocalizations proved far easier to detect than the frogs themselves. Researchers would hear calls ringing through the forest during daylight hours, then spend considerable time pinpointing exactly where they originated.

What makes B. lulai’s call different from its relatives? Each vocalization consists of two notes, with up to four pulses per note. Scientists also detected what they call attenuated notes, softer sounds that precede the main call, almost like the frog is warming up before its full performance.

Over the course of their fieldwork, researchers collected 32 individuals from two locations in the Serra do Quiriri region. Pico Garuva and Monte Crista sit about 6.3 kilometers apart, and scientists believe populations likely exist throughout the forested slopes between these sites. Vocal activity decreased during the hottest afternoon hours but continued throughout most of the day.

Confirmation that B. lulai represented a genuinely new species came through three different methods. Genetic sequencing revealed distinct DNA patterns. Physical examination showed morphological differences from known species, including a rounded snout shape and the absence of a fifth toe. Acoustic analysis demonstrated that calls differed from those of other pumpkin toadlets living in nearby areas.

An Explosion of Discoveries

B. lulai brings the total number of recognized Brachycephalus species to 43, and what’s remarkable is how recently most of these frogs came to scientific attention. Before the year 2000, researchers had described only seven species in the genus. Since then, 36 more have been added to the list.

Advances in DNA sequencing have accelerated these discoveries, allowing scientists to distinguish between species that look nearly identical to the naked eye. Color variations, subtle differences in bone structure, and unique call patterns all help researchers separate one population from another.

Pumpkin toadlets rank among the smallest four-limbed animals on Earth. Extreme miniaturization over evolutionary time has produced some unusual physical traits. Many species have reduced skeletons with missing toe bones, compacted bodies, and shrunken skulls. Some relatives of B. lulai have bones that glow under ultraviolet light, a phenomenon scientists still don’t fully understand.

Perhaps strangest of all, certain pumpkin toadlet species appear deaf to their own calls. Research published in Scientific Reports found that B. ephippium and B. pitanga cannot hear the frequencies they produce. Scientists suspect these frogs may communicate through body movements and visual signals rather than sound, though exactly how remains unclear.

Life in Brazil’s Sky Islands

Serra do Quiriri sits on the border between the Brazilian states of Paraná and Santa Catarina. Mountain peaks rise to over 1,500 meters above sea level, supporting highland grasslands at the highest elevations and dense cloud forests along the slopes. Mist wraps these forests for much of the year, keeping conditions humid and cool.

B. lulai spends its entire life hidden in the damp leaf litter of these cloud forests. Unlike many frog species that become active at night, pumpkin toadlets operate during daylight hours. Researchers recorded individuals calling throughout the day, with only a brief pause during peak afternoon heat.

Biologists sometimes refer to these mountaintop habitats as “sky islands.” Each peak supports its own isolated ecosystem, separated from neighboring mountains by warmer lowlands that ground-dwelling frogs cannot easily cross. For species with limited dispersal abilities, these natural barriers can lead to evolutionary isolation.

B. lulai shares its mountain home with two close relatives. B. auroguttatus and B. quiririensis also occur on Serra do Quiriri, each confined to its own patch of suitable forest. Genetic analysis confirms all three species share a common ancestor, having diverged over thousands of years of isolation.

How Climate Created New Species

What forces drove this diversification? Scientists believe the answer lies in ancient climate fluctuations.

During drier periods in Earth’s history, forests in this region retreated to lower elevations, leaving mountaintops covered in grassland. When wetter conditions returned, cloud forests expanded back upward. But they didn’t spread evenly. Instead, forests grew in isolated patches surrounded by open grassland.

These isolated forest pockets became what researchers call microrefugia. Frog populations trapped in separate patches could no longer interbreed with those in neighboring areas. Over thousands of years, genetic differences accumulated. Physical traits diverged. Calls became distinct. Eventually, separate species emerged from what had once been a single population.

Evidence suggests this process continues today. Researchers have observed Brachycephalus species colonizing newly formed cloud forests at high altitudes, expanding their ranges as vegetation shifts. Climate continues to shape where these frogs can and cannot survive.

Protection for an 8 Square Kilometer World

Despite its striking appearance and evolutionary significance, B. lulai faces an uncertain future. Scientists estimate the species occupies roughly 8 square kilometers of suitable habitat. That’s a remarkably small world for any animal.

Currently, researchers propose classifying B. lulai as “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List. No obvious population declines have been observed, and immediate threats appear limited. But scientists caution against complacency.

“Although Brachycephalus lulai sp. nov. is currently classified as Least Concern, this status is based on the absence of observed ongoing decline and the apparent lack of plausible future threats. Nevertheless, it is essential to continue systematically monitoring this scenario,” the authors wrote.

Surrounding mountains already face pressure from multiple sources. Grassland fires set by humans can spread into adjacent forests. Cattle grazing degrades vegetation and creates erosion. Invasive pine trees alter native plant communities. Roads fragment habitat, and tourism trails can damage sensitive ecosystems if not properly managed.

For species with extremely limited ranges, even localized disturbances can prove catastrophic. A single fire, disease outbreak, or development project could eliminate a significant portion of available habitat.

A Refuge Without Requiring Land Purchase

Researchers have proposed a practical solution. Rather than recommending protected areas that would require government acquisition of private land, a costly and politically complicated process, they suggest creating a Refúgio de Vida Silvestre, or Wildlife Refuge.

Under Brazilian law, this type of conservation unit allows land to remain in private hands while still receiving formal protection. Property owners can continue living on and using their land, provided activities remain compatible with conservation goals.

“The new species is found close to other endemic and threatened anurans, justifying a proposition for the Refúgio de Vida Silvestre Serra do Quiriri, a specific type of Integral Protection Conservation Unit that would not necessitate expropriation of land by the government. This unit would help ensure both the maintenance and potential improvement of the conservation status of these species,” researchers concluded.

Such a refuge would protect not only B. lulai but also its relatives, B. auroguttatus and B. quiririensis, along with other threatened amphibians in the region. Coordinated management could address fire risk, regulate grazing intensity, control invasive species, and guide tourism development.

What One Tiny Frog Means for Conservation

Naming a species after a political leader generates attention, but symbolic gestures alone cannot save endangered wildlife. Long-term protection requires enforcement, community support, and sustained funding. None of these comes easily.

Still, discoveries like B. lulai carry weight beyond their immediate scientific value. Each new species reminds us how much remains unknown about life on Earth. If something as brightly colored as an orange frog can escape detection until 2025, what else might be hiding in remote mountain forests?

Brazil’s Atlantic Forest once covered a vast stretch of the country’s eastern coast. Today, roughly one-fifth of that original forest survives, scattered in fragments of varying sizes. Many of these remnants harbor species found nowhere else on the planet, creatures that evolved in isolation and depend on specific local conditions.

Protecting these fragments means protecting evolutionary history. Millions of years of adaptation, diversification, and survival are encoded in the genes of animals like B. lulai. When a species disappears, that history vanishes with it.

For now, a tiny orange frog continues calling from the misty slopes of Serra do Quiriri. Whether future generations will hear that call depends on decisions made today. Scientists have done their part by documenting what exists and explaining why it matters. What happens next falls to the rest of us.