Your cart is currently empty!

Scientists Find a New Organelle That Evolved Billions of Years After Mitochondria

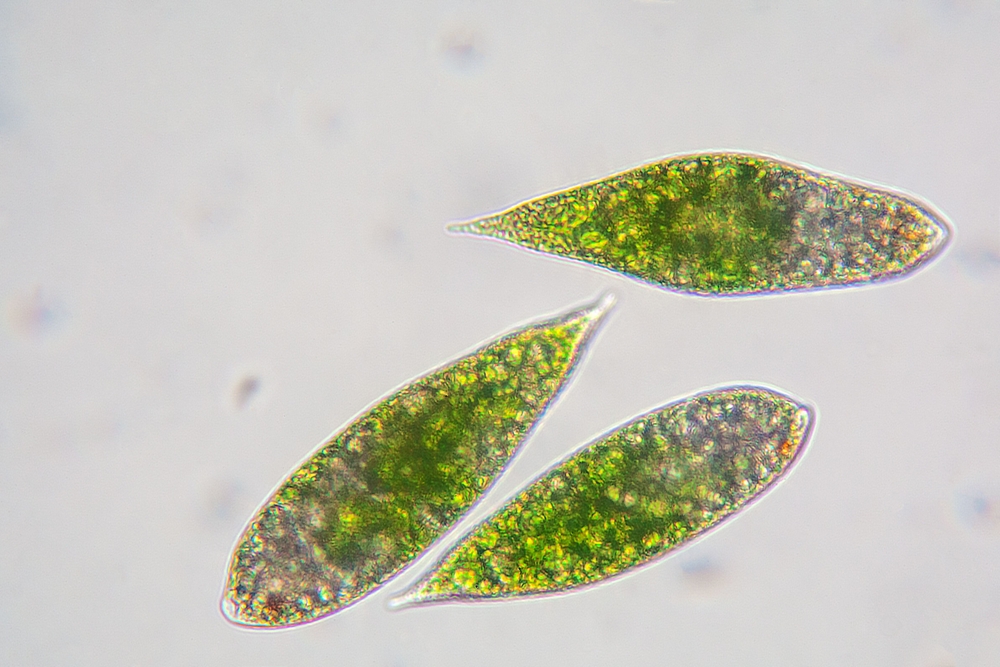

It is one of the most established rules in biology that complex life cannot pull nitrogen from the air on its own. That superpower was supposed to belong exclusively to simple bacteria, while plants and animals were forced to rely on them for survival. But a tiny marine alga found in the ocean has just shattered this assumption. Hidden inside its cells is a rare evolutionary anomaly that scientists haven’t seen in over a billion years, proving that nature is still capable of rewriting its own history.

A Rare Evolutionary Event

For a long time, biology textbooks taught a simple rule about how life sustains itself. The rule was that only bacteria could pull nitrogen from the air and turn it into food. Complex life forms, including plants and animals, cannot do this on their own. They usually rely on bacteria living in the soil or roots to perform this vital task for them.

Recent findings from the University of California, Santa Cruz have changed everything. Scientists found a marine alga that has its own special machinery to fix nitrogen. They call this new cell part the “nitroplast.”

This discovery is a massive deal because such an event is incredibly rare. It occurs when a large cell swallows a smaller microbe but does not digest it. Instead, the microbe becomes a permanent part of the cell, functioning like an organ does in the human body.

This specific type of evolutionary merger has only happened three other times in Earth’s history. It is the same process that created mitochondria, the energy centers in our cells, over a billion years ago. While mitochondria are ancient, this new nitrogen-fixing nitroplast is much younger. It likely evolved only about 100 million years ago.

The Decades-Long Hunt for a Mystery Microbe

This breakthrough did not happen overnight. It was the result of a scientific scavenger hunt that spanned nearly 30 years and crossed oceans. The story began in 1998, when marine scientist Jonathan Zehr found a short, mysterious snippet of DNA in seawater from the Pacific Ocean.

The DNA clearly belonged to a nitrogen-fixing bacterium, which the team labeled UCYN-A. However, they could not find the organism itself. For years, UCYN-A remained a “ghost” in the data. Scientists knew it existed and was important, but they could not see it or study it in a lab.

The turning point came from the work of Kyoko Hagino, a paleontologist in Japan. She was fascinated by a specific marine alga called Braarudosphaera bigelowii. While Zehr was hunting for the bacteria, Hagino was trying to grow this alga in culture tanks, a notoriously difficult task.

Hagino spent more than a decade on this project. She conducted over 300 sampling expeditions to the coastal waters of Japan to collect specimens. Her dedication finally paid off when she successfully grew the alga in her lab. This achievement allowed researchers to combine their efforts. They discovered that the mysterious UCYN-A bacteria were actually living inside Hagino’s algae, setting the stage for their confirmation that these two life forms had merged into one.

Signs of Synchronicity: The Path to Becoming an Organelle

Scientists faced a difficult question: was this microbe just a helpful guest living inside the alga, or had it truly become part of the alga’s body? To find the answer, the research team had to look deep inside the cell’s machinery.

The first clue was synchronization. The team observed that the microbe and the alga grow and divide at the exact same pace. When the alga replicates, the microbe replicates with it. This is a classic behavior of organelles, similar to how mitochondria divide along with the rest of a cell.

The strongest proof, however, came from analyzing proteins. Over millions of years, true organelles lose their own DNA. They stop making everything they need to survive and start relying on the main cell to do the work for them.

The researchers discovered that the nitroplast has done exactly that. It has “thrown away” much of its own genetic instructions. Instead, the alga manufactures specific proteins and ships them into the nitroplast to keep it running. Tyler Coale explained that the alga adds a special label to these proteins, like a shipping address, telling the cell to deliver them directly to the nitroplast.

Visual evidence supported this as well. Using powerful X-ray imaging, the team saw the alga’s mitochondria physically wrapping around the nitroplast. It appeared as though the cell was hugging the new organelle to feed it energy directly. This level of physical and chemical integration confirmed that UCYN-A is no longer an independent bacteria, but a fully integrated part of the host.

A New Hope for Greener Farming

This discovery offers a potential solution to a massive problem in agriculture. To feed the world, farmers rely heavily on artificial fertilizers to give crops the nitrogen they need. Making these fertilizers requires a massive industrial process called the Haber-Bosch process. While it helps grow food for billions of people, it also pumps huge amounts of carbon dioxide into the air.

The nitroplast provides a blueprint for a cleaner way. Nature has shown that it is possible for a complex cell to house its own nitrogen factory. If scientists can crack the code of how this alga maintains its nitroplast, they might be able to teach crops to do the same thing.

Tyler Coale points out that this system gives us a new way to look at nitrogen fixation. It might provide the key to engineering self-sustaining crops in the future. Imagine wheat or corn that grows without needing tons of chemical fertilizer. This would drastically lower pollution and help secure our food supply. It turns out the ocean held the secret to better farming all along.

The Ocean Holds the Key

Finding the nitroplast is not just another scientific footnote. It is a discovery that will rewrite textbooks around the world. For over a century, we believed that only bacteria could fix nitrogen on their own. Now we know that complex life found a way to break that rule.

This finding reminds us that evolution is not just ancient history. It is a creative process that never stops. The merger between this alga and its microbe guest happened relatively recently in geological time. It shows us that nature is constantly experimenting and finding new ways to survive.

As researchers continue to study this tiny marine organism, we may find even more secrets hidden in our oceans. The nitroplast offers a glimpse into the biological machinery that sustains our planet. It turns out that the answers to some of our biggest challenges, from sustainable farming to understanding our own origins, might be floating in a drop of seawater.