Your cart is currently empty!

Heartbreaking Footage Shows Two Orcas Left Trapped in Enclosure in Abandoned Marine Park Months After Closing

They are among the most intelligent and emotionally complex animals on the planet—known to form tight-knit family bonds, mourn their dead, and travel vast ocean distances in tightly synchronized pods. Yet today, two orcas, a mother and her son, spend their lives circling the confines of a concrete tank, cut off not only from the sea but from the very instincts that define their species.

This isn’t a scene from decades past when marine parks thrived on applause and spectacle. This is happening now, in 2025, behind the shuttered gates of Marineland Antibes in the south of France. The park closed months ago, its dolphin and whale shows outlawed by a national ban. But Wikie and Keijo—the country’s last two captive orcas—were left behind.

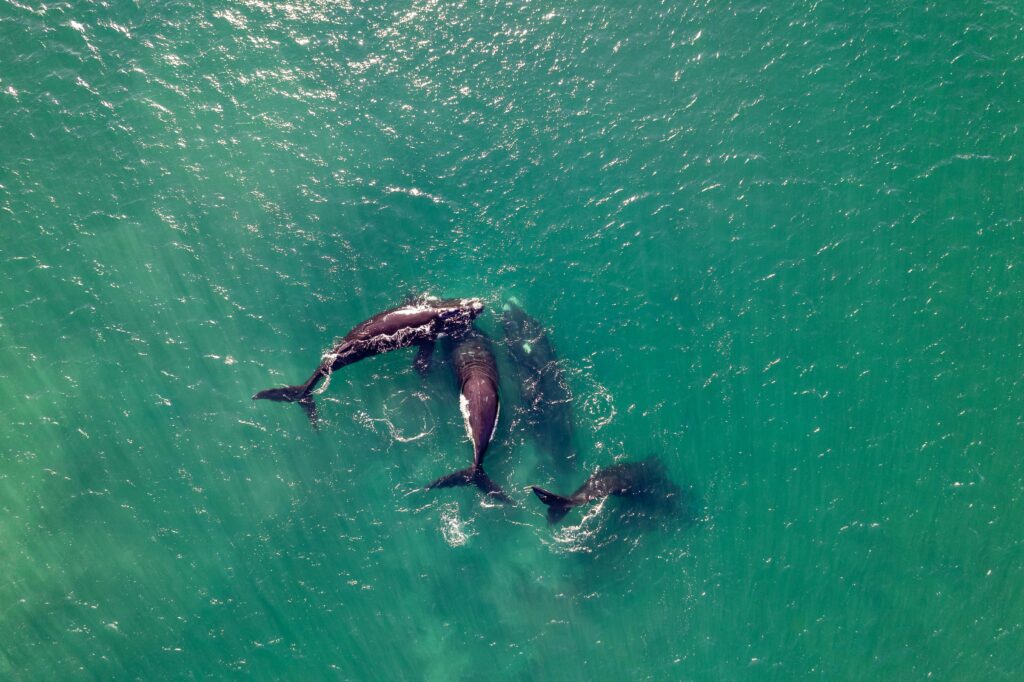

As drone footage surfaces showing the pair swimming aimlessly in algae-streaked enclosures, surrounded by rusting infrastructure and silence, one question hangs heavily in the air: how long can they wait?

Their story is not just about abandonment. It’s about a growing global divide between the ethics of animal captivity and the slow machinery of bureaucracy. It’s about responsibility—who holds it, and who is failing to act.

What the Footage Reveals

The drone footage is as haunting as it is revealing: two orcas—Wikie, 23, and her 11-year-old son Keijo—circle slowly in murky, algae-covered tanks. There is no audience, no trainers, no noise—just the soundless footage of massive, intelligent creatures suspended in limbo. Filmed above the abandoned Marineland Antibes in May 2025, the video has stirred a wave of public outrage and renewed scrutiny of marine mammal captivity in Europe.

Once the pride of France’s largest marine park, Wikie and Keijo are now its most visible remnants—symbols of an outdated industry caught between legislative reform and logistical paralysis. The facility closed its doors to the public in January after a 2021 law banning cetacean performances took full effect. But while human visitors were ushered out, the animals remained behind.

Captured from above, the footage shows water stained green from algae growth clinging to the sides of the tanks. Activist group TideBreakers, who released the video, described the enclosures as “crumbling” and “decrepit,” warning that leaving the orcas in these conditions could lead to illness or even death. Alongside the orcas, twelve dolphins remain confined in similarly deteriorating spaces.

The park’s management insists that appearances are misleading. In statements to the press, they claim the tanks are maintained and the algae is a seasonal phenomenon caused by warming seawater, not harmful to the animals and regularly cleaned. Roughly 50 staff members reportedly continue to care for the marine life daily. Yet for many experts and animal advocates, these assurances feel insufficient against the stark visuals and lack of a concrete relocation plan.

The footage doesn’t show abuse in the traditional sense—it shows abandonment. No enrichment activities. No interaction. Just two beings with nowhere to go, locked in a purgatory of stagnant water and bureaucratic inertia. It’s a view into what happens when progress is made on paper, but the animals at the center of the issue are left waiting for the rest of the world to catch up.

How Did We Get Here?

Founded in 1970, Marineland Antibes was for decades a centerpiece of marine entertainment in Europe. Located on the picturesque French Riviera, it drew millions of visitors eager to witness dolphins, sea lions, and orcas leap and perform in tightly choreographed shows. For years, Wikie and Keijo were star attractions. Wikie, notably, made headlines in 2018 when researchers successfully trained her to mimic human words, including “hello” and “bye bye”—a controversial study that reignited debates around the ethics of using such intelligent animals in captivity.

But behind the curtain of entertainment, public sentiment was shifting. Documentaries like Blackfish and growing awareness of cetacean intelligence prompted international calls for reform. In response, the French government took a definitive stance. In November 2021, France passed a law banning the use of dolphins and whales in live performances, marking a significant turning point. While widely praised by animal welfare advocates, the law left marine parks with a dilemma: what to do with the animals already in their care.

For Marineland Antibes, the decision was closure. By January 2025, the park ceased operations entirely. Yet while the shows ended, the lives they depended on did not. The orcas and dolphins remained, and the park’s responsibility to them continued.

The government’s intention was to find alternative, welfare-centered homes for these animals—ideally within Europe. But as facilities turned out to be inadequate or unwilling, progress stalled. Relocation efforts to a zoo in Japan were blocked by the French Ministry for Ecology. A later plan to transfer the orcas to Loro Parque in Spain, which already houses four orcas, was vetoed by Spanish authorities who deemed the facility too small and potentially unsafe. With each failed attempt, the urgency deepened.

The Human Responsibility: Bureaucracy, Ethics, and Inaction

Behind every stalled relocation, every rejected proposal, and every passing week that Wikie and Keijo remain in their tanks lies a deeper truth: this is not just a logistical failure—it’s a moral one.

Despite Marineland’s official closure, responsibility for the orcas’ welfare did not vanish with its ticket sales. Legally and ethically, the duty to ensure their humane treatment remains intact. Yet the path toward that goal has been consistently obstructed by a tangled web of government preferences, inter-agency delays, and competing visions of what constitutes “appropriate” care.

French authorities, particularly the Ministry for Ecology, have repeatedly stated their preference for a European-based sanctuary. In theory, this would reduce the stress of international transport and keep the orcas within more familiar environmental parameters. In practice, however, no such facility in Europe has met the minimum standards required for orca care—or been willing to take them in. An early plan to relocate the pair to Loro Parque in Tenerife was scrapped after a Spanish scientific panel found the facility lacking in space, depth, and safety. A potential move to a Japanese zoo was similarly blocked by the French government, citing inadequate welfare standards.

All the while, offers from sanctuaries with proven readiness—particularly the Whale Sanctuary Project (WSP) in Nova Scotia, Canada—have been largely ignored or rejected. Lori Marino, president of the WSP, has been vocal about their preparedness. Her team has completed environmental studies, secured a site lease from the Canadian government, and has staff with decades of experience, including key figures involved in the rescue and care of Keiko, the orca made famous in Free Willy. Still, the French government has not responded to the group’s most recent outreach.

“It’s the only option left,” Marino emphasized, underscoring that while Wikie and Keijo cannot be released into the wild due to their lifelong captivity, a natural seaside sanctuary would vastly improve their quality of life. There, they would no longer perform, breed on command, or swim in sterile tanks, but instead live in a semi-wild setting that respects their autonomy and intelligence.

Meanwhile, animal advocacy groups—from Sea Shepherd to Earth Island Institute—have voiced growing frustration. David Phillips of the International Marine Mammal Project praised the Spanish government’s decision to block a move to Loro Parque, but warned that continued delays leave the orcas vulnerable to declining mental and physical health. “Orcas don’t belong in concrete tanks,” he stated bluntly. “They belong in the ocean.”

Even Marineland’s current management has begun sounding the alarm. In a recent public statement, the park called for “the extreme urgency of transferring the animals to an operational destination,” warning that Wikie and Keijo “must leave now” for their own welfare.

This is no longer about choosing between good options. It is about choosing to act at all. The bureaucratic stalemate has real consequences—not for institutions, but for living, feeling beings whose lives continue to play out in slow, circular laps around the same concrete walls.

The Best Way Forward: Sanctuary in Nova Scotia

Among the few proposals still standing, one offers a clear, concrete path forward: the Whale Sanctuary Project (WSP) in Port Hilford Bay, Nova Scotia. More than just a concept, this site represents the most advanced and viable sanctuary ready to receive Wikie and Keijo—if the French government is willing to approve it.

The WSP is not another marine park or aquarium. It is a purpose-built seaside sanctuary designed to provide formerly captive whales with a more natural, enriched environment. While full release into the wild isn’t possible for Wikie and Keijo—both born and raised in captivity—Port Hilford offers a semi-wild coastal refuge with expansive space, natural seawater, and the opportunity for autonomy. Crucially, the orcas would never again be required to perform or breed.

Lori Marino, a neuroscientist and president of the Whale Sanctuary Project, has stressed that the sanctuary has already completed critical groundwork: environmental impact studies, site assessments, and water quality surveys have all been carried out. The project also holds a lease from Canada’s Department of Natural Resources, ensuring legal readiness. “If you don’t even have a site, you’re years away from being a viable sanctuary,” Marino told the BBC. “We have a site. We are ready.”

The sanctuary’s leadership includes figures who played key roles in the story of Keiko—the orca who inspired Free Willy. Both Charles Vinick and Jeff Foster, who helped rehabilitate and rehome Keiko, now lend their expertise to WSP. While Keiko’s return to the wild was unique and ultimately bittersweet—he died of pneumonia after rejoining wild pods in Norway—it proved that better alternatives to permanent concrete captivity exist.

What makes the Nova Scotia sanctuary even more compelling is the widespread expert and public support behind it. Last October, renowned conservationists Dr. Jane Goodall, Dr. Sylvia Earle, and Jean-Michel Cousteau co-signed a letter urging the French government to approve the relocation of Wikie and Keijo to Port Hilford. Their endorsement was not symbolic; it signaled a broader scientific consensus on the ethical imperative to move these animals to more humane conditions.

Despite this, the French Ministry for Ecology has yet to respond to the WSP’s renewed proposal. Previous applications were dismissed on the grounds of “ecological concerns,” though specifics remain vague. Meanwhile, no European sanctuary has materialized. Time continues to pass—and with it, the opportunity to provide Wikie and Keijo with a life that, while not wild, could finally be dignified.

What’s at Stake: The Cost of Delay

Every day that Wikie and Keijo remain in their stagnant tanks, the cost isn’t just symbolic—it’s physiological, psychological, and irreversible.

Orcas are highly intelligent, emotionally complex beings with lifespans comparable to humans. In the wild, they swim up to 100 miles a day, communicate through sophisticated vocalizations, and live in tight-knit family units across generations. In captivity, however, that reality is stripped away. What remains are sterile tanks, manufactured schedules, and, eventually, stress-related illness.

For Wikie and Keijo—both born into human care—the wild is not an option. But nor is indefinite confinement. Marine mammal experts and former trainers have long warned of the toll that life in a concrete enclosure takes: dental damage from gnawing on tank walls, dorsal fin collapse from inactivity and shallow depth, and significant cognitive distress from a lack of stimulation. Prolonged isolation and environmental monotony can trigger anxiety, aggression, and depression. Orcas have even been documented displaying self-harm and repetitive behaviors under such conditions.

Activist group TideBreakers, whose aerial footage reignited public concern, put it starkly: “Should the two orcas fall ill, they will likely be euthanized or succumb to the deteriorating environment.” The longer the delay, the higher the risk of long-term or permanent harm.

Then there’s the broader cost—what it says about our responsibility toward the animals we’ve bred, displayed, and now no longer have use for. Laws have changed, but the lives those laws were meant to protect remain in a holding pattern. The ban on cetacean shows in France was a moral decision, but moral decisions require follow-through. To celebrate a law while neglecting its consequences is to undo its purpose.

Experts estimate that Wikie and Keijo could live for decades longer under proper care. But time is not a neutral factor. The longer they remain in this limbo, the harder it becomes to relocate them safely, to rehabilitate them into new environments, or to undo the damage already done.

What We Owe Them Now

Wikie and Keijo were born into captivity—shaped by a world that treated marine mammals as exhibits rather than individuals. They didn’t choose this life, nor can they survive in the wild. But that doesn’t mean they must remain forgotten, circling endlessly in a tank that was never built for a lifetime.

The world is watching, and not just because of drone footage or viral headlines. This moment matters because it encapsulates a larger reckoning: how we treat the beings we once used for entertainment when their roles have expired. Do we merely acknowledge our past mistakes, or do we correct them?

The tools are there. The sanctuary is ready. The science is clear. What’s missing is the will.

Animal welfare isn’t only about prevention of cruelty—it’s about the presence of compassion. And compassion, in this case, means making the hard, expensive, and urgent choice to relocate Wikie and Keijo to a place where they can live out their lives with dignity. Not because they can be rewilded, but because they are still alive—and that still means something.

The longer their tanks remain full but their futures empty, the louder the silence becomes. But silence, as we know, can be broken. The question now is: will we listen, and act—before it’s too late?