Your cart is currently empty!

Indonesian Cave Discovery Rewrites the History of Art

For years, visitors walked through a limestone cave on a small Indonesian island, captivated by scenes of animals, boats, and human figures painted thousands of years ago. Few realized that something far older was watching them from the walls, so faint it blended almost seamlessly into the stone itself.

What looked like nothing more than a natural discoloration has now been identified as the oldest known example of cave art ever discovered. A single hand stencil, created at least 67,800 years ago, is forcing scientists to rethink when humans first began expressing themselves symbolically and where the roots of art truly lie.

This discovery, published in the journal Nature, is not just about an ancient handprint. It is about human imagination, migration, and the surprising places where our earliest creative instincts emerged.

A Cave Hiding a Secret in Plain Sight

The discovery comes from Liang Metanduno, a limestone cave on the island of Muna in Indonesia’s Southeast Sulawesi province. The cave has long been known to archaeologists and tourists alike. Its walls are decorated with paintings of chickens, boats, and mounted warriors believed to be only a few thousand years old.

In 2015, Indonesian archaeologist Adhi Agus Oktaviana noticed something unusual while studying the cave’s interior. Beneath the more recent paintings, he spotted faint red shapes that did not look natural. They appeared to be hand stencils, but they were so faded that they had escaped notice for decades.

According to researchers, these markings were easy to miss. Mineral deposits had formed over the artwork, dulling its color and blurring its outlines. Without careful inspection, the handprint could easily be mistaken for a stain or shadow in the rock.

That moment of curiosity would eventually lead to one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the century.

How Scientists Dated a Nearly Invisible Handprint

Dating ancient rock art is notoriously difficult. Unlike charcoal drawings found in Europe, many paintings in Southeast Asia were made with ochre, a mineral pigment that cannot be carbon dated.

To determine the age of the hand stencil, researchers used uranium series dating. This method analyzes tiny amounts of uranium in calcium carbonate deposits that formed on top of the artwork. Because these mineral layers accumulated after the painting was created, they provide a minimum age for the art beneath them.

The results were staggering. The hand stencil was found to be at least 67,800 years old, making it older than any previously dated cave art anywhere in the world.

Some scientists caution that the technique provides a minimum age rather than an exact creation date. The hand could be even older, but researchers cannot yet determine how much earlier it was made.

Despite this uncertainty, independent experts have described the dating as sound and the implications as extraordinary.

A Hand That Looks More Like a Claw

At first glance, the artwork appears simple. It shows the outline of a human hand created by blowing pigment around fingers pressed against the cave wall. But a closer look reveals something unusual.

The fingers appear elongated and sharply pointed, almost claw-like in shape. This feature is not common in hand stencils from other parts of the world, but it does appear in other cave art found in Sulawesi.

Researchers believe this was a deliberate artistic choice rather than an accident. Some suggest the artist may have altered the position of their fingers or retouched the image to transform a human hand into something more animal-like.

Why they did this remains a mystery. One theory is that it reflects early beliefs about human-animal relationships, identity, or transformation. Others caution that erosion or pigment flow could explain the shape, though many experts believe the modification was intentional.

Regardless of interpretation, the hand stencil shows a level of creativity that challenges old assumptions about early human cognition.

Rethinking Where Art Began

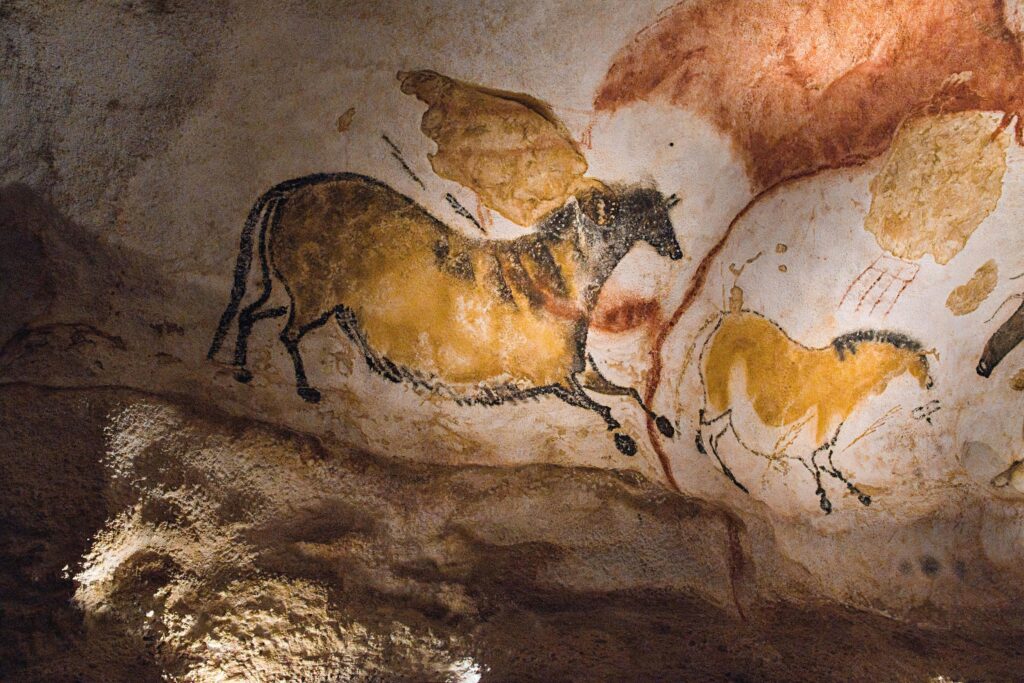

For much of the last century, Europe was seen as the birthplace of symbolic human culture. Cave paintings in France and Spain, dating back 30,000 to 40,000 years, were considered evidence of the moment when humans became truly artistic.

Discoveries in Indonesia over the past decade have steadily dismantled that narrative. Earlier studies in Sulawesi revealed paintings of human-animal hybrids and hunting scenes dating back more than 50,000 years.

The newly dated hand stencil pushes that timeline even further into the past. It suggests that humans were creating symbolic art tens of thousands of years before similar works appeared in Europe.

This does not mean Europe was unimportant in the history of art. Instead, it shows that creativity emerged in multiple regions and was likely already well established before humans spread across the globe.

A Long Tradition, Not a Single Moment

One of the most striking aspects of the Liang Metanduno discovery is what it reveals about continuity.

The cave was not decorated during a brief burst of creativity. Evidence suggests it was used repeatedly over tens of thousands of years. Art was produced there during the Ice Age, stopped during periods of environmental change, and resumed thousands of years later by early farming communities.

This long sequence shows that symbolic expression was not an isolated innovation. It was a cultural tradition passed down through generations, adapted and reimagined as societies changed.

Such continuity challenges the idea that art suddenly appeared as a revolutionary leap in human behavior. Instead, it points to creativity as a fundamental and enduring part of being human.

Who Made the World’s Oldest Cave Art

The researchers behind the study believe the hand stencil was most likely created by Homo sapiens. The complexity of the finger shapes and the timing of modern human arrival in the region support this conclusion.

However, they do not rule out other possibilities. Neanderthals are known to have made hand stencils in Europe, and another ancient human group known as Denisovans once lived in parts of Asia.

Because human remains from this period are rare in Sulawesi, rock art remains one of the few clues available to identify who lived there tens of thousands of years ago.

The debate highlights how much remains unknown about early human populations in Southeast Asia.

A Clue to Humanity’s Epic Migration

The implications of the discovery extend far beyond art history.

Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests modern humans reached the ancient landmass of Sahul, which combined Australia and New Guinea, around 65,000 years ago. Getting there required deliberate ocean crossings, representing some of the earliest known seafaring journeys.

Sulawesi sits along a proposed northern migration route into Sahul. The presence of sophisticated cave art dating back nearly 68,000 years provides strong evidence that modern humans were living along this corridor during that time.

This supports the idea that the artists who left their handprint on the cave wall may have been ancestors of Indigenous Australians.

Challenging Eurocentric Ideas of Intelligence

For decades, limited dating technology made it difficult to accurately assess the age of ochre-based rock art outside Europe. As a result, early human intelligence was often framed through a European lens.

New dating techniques are now revealing a much broader picture. They show that people living in Southeast Asia possessed advanced cognitive abilities long before similar evidence appears in Europe.

These early artists were capable of imagination, symbolism, and possibly storytelling. They altered images, combined human and animal traits, and marked places with meaning.

Such findings challenge outdated notions of where and when modern human behavior emerged.

Why the Discovery Matters Today

Beyond its scientific significance, the hand stencil invites reflection on what it means to be human.

Across tens of thousands of years, separated by oceans, climate shifts, and technological revolutions, people have felt the urge to leave marks behind. A simple hand pressed against stone becomes a declaration of presence, identity, and connection.

The fact that this image survived, hidden beneath layers of time, reminds us how fragile and precious our shared history is.

How Much More is Still Undiscovered

Large parts of Indonesia and neighboring islands remain archaeologically unexplored. Dense forests, remote terrain, and limited funding mean many caves have never been systematically studied.

If one of the world’s most important artworks could hide in plain sight at a popular tourist site, researchers believe many more discoveries may still be waiting.

Future finds could push the timeline of human creativity even further back, reshaping our understanding of where culture began.

A Hand Reaching Across Time

The faint red outline in Liang Metanduno is easy to overlook. Yet it carries a message that has traveled nearly 70,000 years.

It tells a story of humans who imagined, experimented, and expressed themselves long before written language or recorded history. It suggests that creativity was not a luxury of settled societies, but a core part of survival and identity.

As scientists continue to explore the caves of Indonesia, one thing is already clear. The story of human creativity is older, richer, and far more geographically diverse than we ever imagined.

And it all began, quietly, with a hand pressed against stone.