Your cart is currently empty!

Scientists Capture the Smallest Slice of Time Ever Measured

Time is something humans instinctively feel they understand because it structures every part of daily life. We wake up according to clocks, plan our futures in years, and measure our achievements by hours worked or moments remembered. Because of this familiarity, it is easy to assume that time itself is a simple concept that merely flows forward at a steady pace. Yet beneath this everyday experience lies a reality that behaves in ways completely detached from human intuition. For centuries, scientists believed that while time could theoretically be divided into ever smaller pieces, there would always be a practical limit to what could actually be measured. The deeper layers of time were thought to exist only in theory, far beyond the reach of observation.

That assumption has now been overturned in remarkable fashion. Scientists have successfully measured the shortest unit of time ever recorded by capturing the moment it takes for a particle of light to cross a single hydrogen molecule. This was not a conceptual exercise or a mathematical approximation, but a real physical event measured directly using advanced experimental tools. The result does more than set a scientific record. It reveals new information about how light interacts with matter and shows that even within a single molecule, events unfold in a precise sequence rather than all at once. In doing so, the discovery pushes human understanding deeper into the fundamental mechanics of the universe than ever before.

A Measurement at the Edge of Reality

The time measured in this experiment was 247 zeptoseconds, a number so small that it challenges comprehension even when carefully explained. A zeptosecond is a trillionth of a billionth of a second, written as a decimal point followed by twenty zeros and then a one. In the time it takes a human eye to blink, an unfathomable number of zeptoseconds have already passed. Each one exists so briefly that it disappears almost as soon as it comes into being, making the idea of measuring it seem almost impossible.

What makes this measurement extraordinary is that it represents the shortest span of time ever directly observed and calculated through an experimental process. This was not inferred indirectly or extrapolated from theory, but tied to a real event occurring inside a molecule. The researchers were able to associate the measurement with a physical interaction, grounding it firmly in observable reality rather than abstract mathematics. That distinction is critical because it demonstrates that even the most fleeting moments can be captured with the right tools.

For decades, physicists suspected that events occurring at this scale were effectively invisible, hidden beneath layers of uncertainty and technological limitation. Achieving this level of precision shows that those barriers were not fundamental laws of nature, but challenges waiting to be overcome. As measurement techniques continue to improve, the boundary between what is theoretically possible and what is experimentally observable continues to shrink.

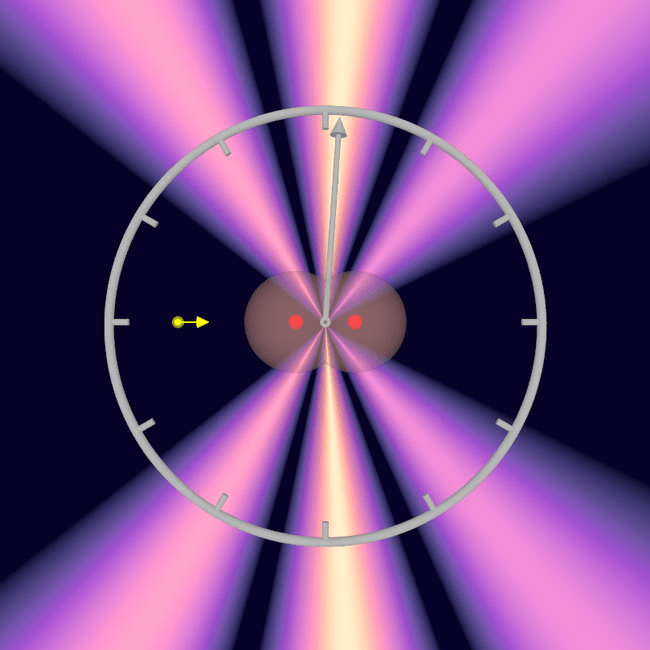

Image Credit: Sven Grundmann, Goethe University Frankfurt

How Scientists Reached the Zeptosecond Frontier

The ability to measure time at this scale did not emerge suddenly. It is the result of decades of incremental progress in experimental physics. In 1999, Nobel Prize winning research first succeeded in measuring events occurring in femtoseconds, which are millionths of a billionth of a second. That breakthrough allowed scientists to observe chemical reactions as they happened, fundamentally changing how chemistry and materials science were understood.

As laser technology and detection methods improved, researchers pushed further. By 2016, scientists had managed to measure time intervals as short as 850 zeptoseconds, a feat that already seemed close to the edge of experimental feasibility. At the time, many believed that further progress would be extremely difficult due to the limitations of existing instruments.

The new measurement represents a significant leap beyond those earlier achievements. By reducing the measurable interval to 247 zeptoseconds, scientists crossed from observing atomic motion into directly observing the movement of light itself. This shift marks an important moment in physics, as it brings phenomena once confined to theoretical discussion into the realm of direct measurement.

Why Hydrogen Was the Perfect Choice

To observe such an incredibly brief event, researchers needed a system that was as simple and predictable as possible. They chose a hydrogen molecule, which consists of two protons and two electrons. This simplicity makes hydrogen ideal for experiments that require extreme precision, as it minimizes variables that could complicate the results.

More complex molecules introduce additional interactions that can obscure subtle timing differences. Hydrogen, by contrast, allows scientists to model interactions with a high degree of accuracy. In an experiment where every fraction of a zeptosecond matters, having such a clean and well understood system is essential.

The goal was to measure how long it takes for a photon, a particle of light, to travel from one hydrogen atom to the other within the same molecule. That distance is unimaginably small, yet the experiment showed that even across this tiny span, time still unfolds in a measurable and orderly way.

Using X Rays to Track Light Inside a Molecule

To capture this ultrafast journey, researchers fired X-rays at hydrogen molecules using a powerful particle accelerator. The energy of the X-rays was carefully calibrated so that a single photon would interact with the molecule in a controlled and measurable way. This precise tuning was essential for isolating the event scientists wanted to observe.

When the photon struck the molecule, it knocked out one electron and then the other. The process was compared to a pebble skipping across water, with the photon briefly interacting with each part of the molecule in sequence. These interactions happened at extraordinary speed, but they left behind a measurable signature.

That signature took the form of overlapping electron waves that created an interference pattern. This pattern contained detailed information about the timing of the interactions, allowing researchers to reconstruct the path of the photon as it moved through the molecule.

Decoding the Interference Pattern

To analyze these interactions, scientists used an extremely sensitive reaction microscope capable of recording ultrafast atomic events. The instrument captured both the interference pattern and the precise position and orientation of the hydrogen molecule throughout the interaction, providing a complete picture of what occurred.

Because the spatial orientation of the molecule was known, the researchers could calculate the tiny delay between when the photon reached the first hydrogen atom and when it reached the second. As one of the study’s authors explained, “Since we knew the spatial orientation of the hydrogen molecule, we used the interference of the two electron waves to precisely calculate when the photon reached the first and when it reached the second hydrogen atom.”

The resulting measurement was 247 zeptoseconds, with slight variation depending on the exact distance between the atoms at that moment. This effectively captured the speed of light operating within the molecule itself, a remarkable achievement that turns an abstract constant into a directly measured process.

What the Discovery Reveals About Light and Matter

One of the most important findings from this experiment is that light does not influence an entire molecule simultaneously. Instead, its effects spread through the molecule at the speed of light, creating measurable delays even within an extremely small system. This challenges simplified assumptions about how molecules respond to electromagnetic radiation.

As the lead researcher stated, “We observed for the first time that the electron shell in a molecule does not react to light everywhere at the same time.” This delay occurs because information inside the molecule spreads at a finite speed, rather than instantaneously.

The result reinforces a fundamental principle of physics, that causality applies at every scale of reality. Even within a single molecule, events happen in sequence, governed by the same physical laws that shape the larger universe.

Why Measuring Time This Short Matters

At first glance, measuring zeptoseconds may seem disconnected from everyday life, but its implications are far reaching. Understanding how light and matter interact at such short timescales is essential for refining quantum theory and improving experimental methods across many scientific fields.

The techniques developed for this experiment could eventually allow scientists to observe electron motion in complex molecules, study energy transfer in biological systems, or design faster electronic and photonic technologies. Each advance in time resolution opens new doors for discovery.

History shows that breakthroughs in measurement often lead to applications that were not originally anticipated. What begins as a record breaking scientific achievement can later become the foundation for technologies that reshape society.

Looking Into an Invisible World of Time

This achievement serves as a reminder of how much of reality operates beyond human perception. Beneath the steady flow of seconds that structure daily life lies a world where events unfold in intervals so small they were once thought impossible to observe.

Each improvement in measurement technology expands not only scientific knowledge but human perspective. It shows that the universe remains understandable even at scales that challenge imagination, governed by precise laws waiting to be uncovered.

By measuring the shortest unit of time ever recorded, scientists have demonstrated that no moment is truly beyond reach. In doing so, they have opened the door to exploring even deeper layers of time that may still lie ahead.