Your cart is currently empty!

Scientists Just Found a New Way for Gears to Work Without Touching and It Could Change How Machines Are Built

Many of the mechanisms that support modern life operate out of sight and out of mind. We trust them because they have worked for generations, and that familiarity creates a quiet confidence that their design is settled. Over time, usefulness turns into assumption, and assumption turns into habit, leaving little room to wonder whether these systems could function differently.

Now, some researchers are returning to one of these long standing designs with a different mindset. Instead of focusing on improvement, they are questioning necessity, looking closely at what was chosen long ago and why it stayed unchanged. Their work invites a broader reflection on how progress happens and whether innovation sometimes begins not with adding more, but with asking what we no longer need, so which ideas have we accepted simply because they have always been there?

When Early Ingenuity Met Its Limits

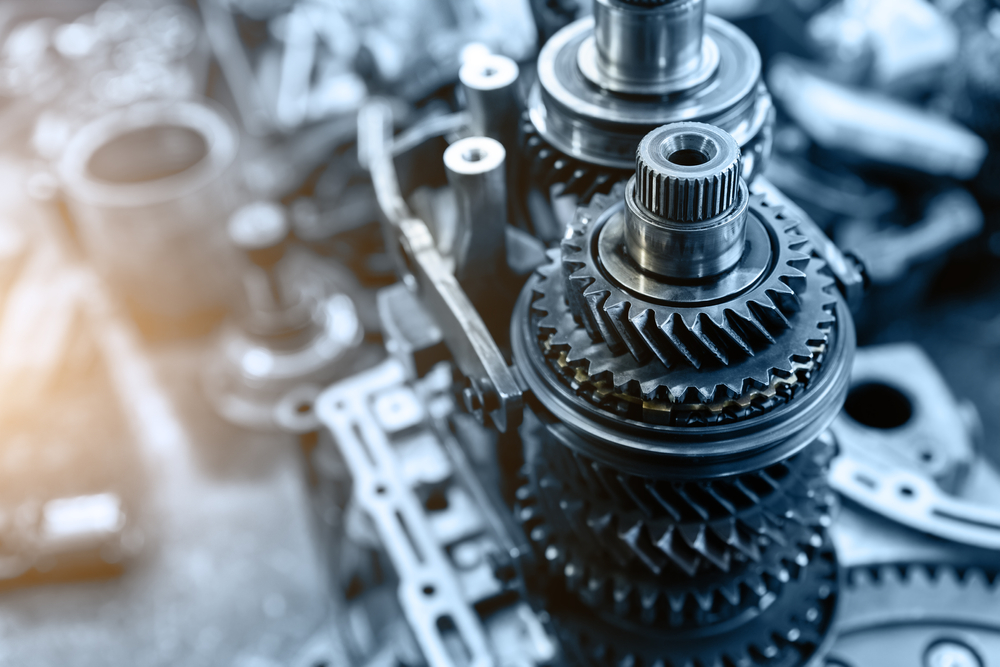

Long before modern engineering textbooks existed, people were already solving complex mechanical problems by closely observing the natural world. In China around the third century BCE, engineers built what is considered the first differential gear system to power the south pointing chariot, a vehicle designed to keep its directional pointer steady no matter how the wheels turned. In ancient Greece, a very different but equally sophisticated device took shape in the Antikythera Mechanism, an intricate network of gears used to predict astronomical events. Even today, researchers continue to study it to understand how such precision was achieved with the tools available at the time. These machines show that early engineers were careful thinkers who understood motion, balance, and cause and effect at a deep level.

At the same time, these designs shared a common limitation that persisted across centuries. Traditional gears depend on solid contact between teeth, and that contact only works well when alignment is maintained with extreme precision. Over time, real world conditions interfere with that precision. Materials expand with heat, surfaces change with repeated use, and lubricants break down or shift away from contact points. Each small change affects how smoothly motion is transferred, and over long periods those effects add up to noise, energy loss, and wear. Because of this sensitivity, gear based systems require careful manufacturing, regular maintenance, and protective measures to remain reliable, especially in environments exposed to dust, moisture, or temperature changes.

Engineers have historically addressed these challenges by adding housings, lubrication systems, and tighter tolerances, improving performance while increasing complexity and cost. As machines shrink in size, these tradeoffs become even more difficult to manage, since minor imperfections can dominate behavior. Rather than reflecting a failure of early design, this limitation highlights a physical boundary tied to constant contact between moving parts, one that has quietly shaped how mechanical systems evolve.

Letting Liquid Do the Work

Rather than refining traditional gears, researchers at New York University took a step back and reconsidered how motion itself might be transferred. Their study, published in Physical Review Letters, examined whether rotation could move from one object to another without solid parts touching. The idea centered on using fluid motion as the connecting force, shifting attention away from mechanical contact and toward how liquids behave when set in motion.

To explore this, the team led by Jun Zhang, with Leif Ristroph and doctoral researcher Jesse Etan Smith, placed two identical cylindrical rotors into a thick glycerol water mixture. One rotor was powered by a motor, while the other was left unpowered and allowed to respond only to the movement of the surrounding liquid. Small air bubbles were introduced into the mixture so the researchers could observe how the fluid carried motion through the space between the rotors. This setup made it possible to track how rotation was transmitted without relying on interlocking parts.

The results pointed to a new way of thinking about gears. As Zhang explained in a press statement, “We invented new types of gears that engage by spinning up fluid rather than interlocking teeth,” adding that the system revealed “new capabilities for controlling the rotation speed and even direction.” By relying on flow instead of contact, the experiment challenged long held assumptions about how mechanical motion must work and opened the door to designs that operate under entirely different constraints.

When Flow Changes the Rules of Motion

As researchers adjusted how the fluid based system operated, they noticed that motion did not follow a single fixed pattern. When the two rotors were placed close together and moved at lower speeds, the liquid trapped between them behaved much like the teeth of a conventional gear. That confined flow pushed the passive rotor to turn in the opposite direction of the driven one, matching what engineers would normally expect from interlocking parts. Under these conditions, fluid acted as a temporary mechanical link, even though no solid contact was involved.

The behavior shifted as soon as spacing or speed changed. When the rotors were placed farther apart or rotated more quickly, the fluid no longer stayed confined between them. Instead, it swept around the outer surface of the passive rotor, pulling it into motion in the same direction as the active one, similar to how a belt transfers motion between pulleys. This flexibility is one of the system’s defining features. As Leif Ristroph explained, “Regular gears have to be carefully designed so their teeth mesh just right, and any defect, incorrect spacing, or bit of grit causes them to jam. Fluid gears are free of all these problems, and the speed and even direction can be changed in ways not possible with mechanical gears.” What mattered was not how the system had behaved before, but the conditions in that moment, which reliably determined the outcome.

The reason for these reversals lies in how fluid forces compete around the passive rotor. Liquid moving along the inner side pushes rotation one way, while flow sweeping around the outer side pushes the other. Which influence dominates depends on spacing and speed. As Jun Zhang explained in an interview, “At very small gaps, the inner shear region shrinks, letting outer flow dominate and causing same direction rotation. At intermediate gaps, inner shear regains control, restoring counterrotation. At larger distances, the overall flow pattern reorganizes again, flipping the outcome once more.” Faster rotation amplifies these effects by increasing inertia, causing fluid to spiral outward instead of looping tightly. Together, these findings show that motion in fluid driven systems is shaped by context, with small changes producing predictable but very different results.

Why Reliability Matters More Than Precision

One of the quieter takeaways from this research is how it challenges the way engineers usually define reliability. Traditional mechanical systems are often judged by how precisely they can be built and maintained. Success depends on keeping parts aligned within narrow limits, which works well in controlled settings but becomes harder to sustain in real world conditions. Dust, temperature changes, vibration, and long term use all introduce variation that precision alone cannot fully eliminate.

The fluid based approach shifts that balance. Instead of depending on exact positioning, performance depends on broader conditions such as spacing and speed, which can be adjusted without physical wear. That difference matters because many systems fail not due to sudden breakdowns, but because small imperfections accumulate over time. Designs that tolerate variation tend to degrade more gradually and predictably, rather than abruptly.

This perspective helps explain why the research has drawn attention beyond a single experiment. It highlights a design philosophy that values stability through flexibility rather than control through rigidity. In fields where machines must operate for long periods with limited oversight, such as remote infrastructure or sealed devices, this distinction can be more important than achieving perfect mechanical precision from the start.

How This Could Change Long Term Maintenance

Another aspect of this research that has received less attention is how it reframes the idea of maintenance. Traditional mechanical systems are built with the expectation that parts will wear down. Regular inspection, lubrication, and replacement are treated as unavoidable costs of operation. Over time, maintenance becomes a defining factor in how long a machine remains useful, especially in settings where access is limited or downtime is expensive.

By removing direct contact between moving parts, fluid driven systems change that equation. Without surfaces grinding against each other, the primary sources of wear shift away from physical damage and toward controllable operating conditions. Instead of replacing worn components, adjustments can be made by altering speed, spacing, or fluid properties. This does not eliminate maintenance, but it changes its nature from reactive repair to ongoing regulation.

That distinction matters for systems expected to run continuously or in environments where intervention is difficult. Machines that fail gradually and predictably are easier to manage than those that depend on precise parts staying intact. In this sense, the research points toward designs that prioritize longevity and stability over short term performance, offering a different way to think about how machines age and how their care is planned over time.

When Old Assumptions Finally Give Way

What makes this research stand out is not just the technical achievement, but the shift in perspective it represents. For centuries, gears have been built around the idea that solid contact is unavoidable, and entire systems have evolved to manage the consequences of that choice. By showing that motion can be guided through fluid instead, researchers have demonstrated how deeply held assumptions can quietly shape progress, even when better alternatives are possible.

The story of fluid driven gears is ultimately about paying attention. It is about noticing where designs struggle, understanding why they fail, and being willing to rethink fundamentals rather than endlessly refining them. As this work shows, meaningful advances often emerge not from adding more complexity, but from questioning what was once considered essential.