Your cart is currently empty!

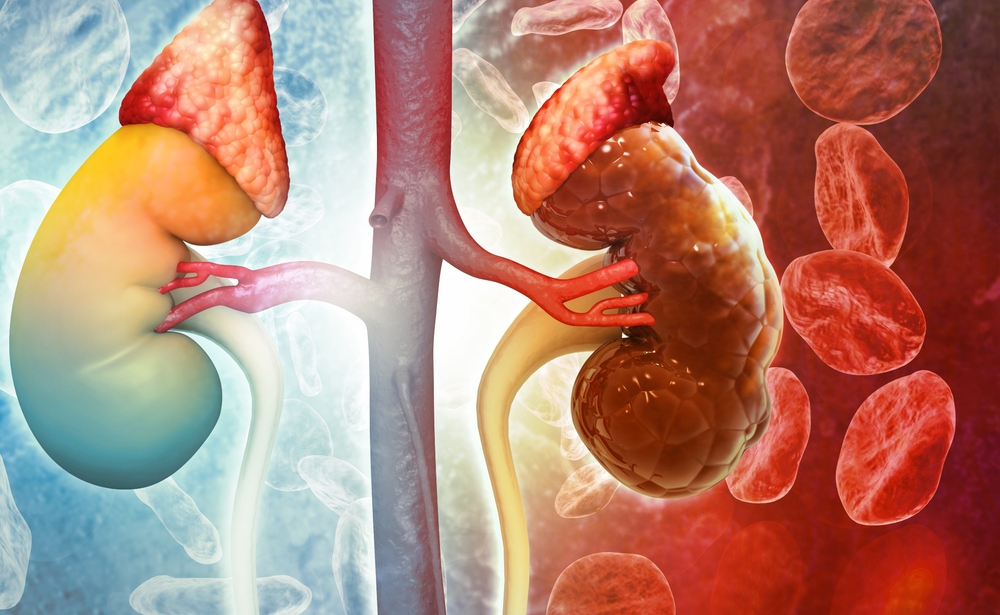

A Wearable Kidney May Finally Free Patients From Hospital Dialysis and Restore Real Independence

Every week, hundreds of thousands of people in the United States are tethered to dialysis machines three times a week, four hours at a stretch just to stay alive. That means countless hours spent in clinics instead of at work, with family, or simply living life on their own terms. For many, the treatment feels like a second job they never asked for, one that comes with punishing side effects and strict rules about what to eat, drink, and do.

Now imagine shrinking that machine down to something no larger than a paperback book or even smaller and making it wearable or implantable, so that it works quietly in the background, just as a healthy kidney would. That vision is inching closer to reality. Scientists are racing to develop a bioartificial kidney that could free patients from hospital dialysis, bypass the shortage of donor organs, and restore something dialysis rarely offers: real independence.

The Burden of Dialysis Today

Dialysis has been a lifeline for people whose kidneys no longer function, but it comes at a steep cost. More than half a million Americans depend on it, usually through hemodialysis performed in hospitals or dialysis centers three times a week. Each session lasts about four hours, which adds up to hundreds of hours per year tethered to a machine. The sheer time commitment is exhausting, but the hidden toll is even greater.

Dialysis is not a perfect substitute for the kidneys’ constant, round-the-clock work. Healthy kidneys filter blood continuously, keeping fluid levels, electrolytes, and waste products in balance. Dialysis, by contrast, works intermittently, so toxins and fluids build up between sessions. Patients often describe feeling drained or unwell after treatment, plagued by nausea, dizziness, or muscle cramps. Between treatments, they must follow strict limits on what they eat and drink to prevent dangerous fluid overload and imbalances in potassium or phosphate that can threaten the heart.

The consequences ripple beyond physical health. Research shows that dialysis patients experience higher rates of depression, social isolation, and unemployment. Even peritoneal dialysis, which allows patients to treat themselves at home, has limitations. It can only be used for a few years before the peritoneal membrane becomes less effective, often forcing patients back to hospital-based care.

Despite its life-saving role, dialysis remains a demanding, imperfect therapy. For many, it feels like survival on borrowed time waiting for a transplant that may never come, while struggling with the daily compromises the treatment demands.

Why Innovation Is Urgently Needed

Kidney transplantation is widely considered the gold standard treatment for end-stage kidney disease, but access is severely limited. In the United States, the median wait time for a transplant is 3.6 years, and only about 20,000 transplants take place annually far fewer than the number of people who need them. Even when a transplant is possible, the challenges don’t end. Patients must take immunosuppressant drugs for life to prevent rejection, exposing them to increased risks of infection, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of patients are left relying on dialysis. Though it sustains life, dialysis cannot fully replicate the kidneys’ continuous regulation of waste, electrolytes, hormones, and blood pressure. This gap between “survival” and “thriving” is what makes kidney failure such a devastating condition. Patients may live longer thanks to dialysis, but the quality of that life is often diminished.

The urgency for new solutions is magnified by the scale of the problem. Kidney disease affects nearly 37 million Americans more than one in seven adults and it causes more deaths than breast cancer or prostate cancer. Around the world, roughly 3 million patients rely on dialysis, and that number is projected to grow as rates of diabetes and hypertension rise. The current system is strained: too few organs, costly treatments, and millions of people locked into a cycle of care that preserves life but often limits living.

This is why the search for alternatives wearable devices, implantable bioreactors, or entirely new approaches is not just about convenience. It is about transforming kidney care from a stopgap measure into a pathway toward independence, dignity, and better health outcomes.

The Promise of a Wearable or Implantable Artificial Kidney

Imagine replacing the hours spent each week in a dialysis chair with a device that works silently and continuously, just like a healthy kidney. That vision is what drives researchers developing wearable and implantable artificial kidneys. These technologies aim to replicate the kidneys’ core functions filtering toxins, balancing fluids and electrolytes, and regulating blood pressure without the need for constant hospital visits.

One of the most ambitious efforts is The Kidney Project, a collaboration between scientists at UC San Francisco and Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Their bioartificial kidney combines two components: a filter to remove waste from the blood and a bioreactor filled with human kidney cells that carry out vital regulatory functions. The device has already passed an important milestone surviving inside pigs for a week while performing kidney-like tasks without triggering immune rejection. “We are focused on safely replicating the key functions of a kidney,” said Dr. Shuvo Roy, the project’s technical director. “The bioartificial kidney will make treatment for kidney disease more effective and also much more tolerable and comfortable.”

Wearable devices are also advancing. In 2016, a portable “wearable artificial kidney” weighing about 5 kilograms allowed patients to move freely during 24-hour treatment sessions, showing encouraging results in toxin removal. More recently, companies like AWAK Pte Ltd have tested lighter devices for peritoneal dialysis, achieving clinically significant reductions in urea and creatinine while patients carried on daily life. These trials demonstrate the potential for smaller, more mobile dialysis systems that extend freedom and flexibility.

What makes both approaches extraordinary is not just the engineering, but the promise of restoring independence. Instead of planning life around dialysis sessions, patients could live, travel, and work with far fewer constraints. For families, it could mean fewer emergencies, less financial strain, and more normalcy. For healthcare systems, it offers a chance to ease the enormous costs of in-center dialysis, which in the U.S. alone consumes billions of dollars each year.

How the Technology Works

At its core, the challenge of building a wearable or implantable kidney is deceptively simple: mimic what healthy kidneys do automatically, 24 hours a day. The reality, however, is far more complicated. Kidneys aren’t just filters; they are sophisticated regulators that maintain the body’s chemical balance, control blood pressure, and even release hormones. Any artificial device must handle both the mechanical task of cleaning blood and the biological finesse of keeping the body in balance.

The most advanced designs combine two key systems. First is a filtration unit that removes waste products and excess water from the blood. Second is a bioreactor, filled with living kidney cells, that performs critical functions such as balancing salts, managing fluid levels, and producing regulatory hormones. To protect these cells from attack by the body’s immune system, researchers use ultra-thin silicon membranes that allow nutrients and oxygen to pass through while blocking immune cells. This shield means the device could operate without the need for lifelong immunosuppressant drugs a major improvement over traditional transplants.

Waste management is another technical frontier. Of all the toxins that kidneys normally clear, urea presents the biggest obstacle. It is produced in large quantities every day and is notoriously difficult to remove efficiently. Scientists are experimenting with several methods, from enzymes that break urea into other compounds, to electrochemical systems that decompose it into harmless gases, to advanced sorbents that can trap it. Each approach has strengths and limitations enzymes risk producing toxic byproducts, electrochemical methods must avoid generating harmful chemicals, and sorbents often struggle with low efficiency. The search for the most practical, safe, and miniaturized solution continues.

What’s Next for Patients

The artificial kidney is no longer just an idea on the horizon it is entering the crucial stage where science meets patient reality. Early successes in animal studies and small human trials show the concept works, but the road from prototype to widespread use is long and carefully regulated. Devices must undergo extended testing to prove they can operate safely for months at a time without complications, and they must clear rigorous review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration before patients can benefit.

Encouragingly, momentum is building. The Kidney Project recently received a $650,000 KidneyX prize, a joint initiative of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, designed to accelerate breakthroughs in kidney care. Pilot trials of wearable dialysis devices have also given patients a taste of what life could look like with more freedom and mobility. These milestones signal not just scientific progress but a growing recognition that kidney failure demands bold new solutions.

For patients and families, the potential impact is enormous. Instead of organizing their lives around dialysis schedules, they could travel, work, and socialize with fewer restrictions. The risk of cardiovascular complications, hospitalizations, and treatment-related exhaustion could diminish, improving both survival and quality of life. For healthcare systems, a shift toward wearable or implantable kidneys could ease the financial burden of in-center dialysis, which currently costs billions annually in the United States alone.

Restoring Freedom, One Kidney at a Time

For decades, dialysis has been a necessary compromise prolonging life but rarely restoring the independence and vitality patients long for. The promise of wearable and implantable artificial kidneys changes that equation. It suggests a future where treatment doesn’t dictate daily life, where patients can move, work, and dream without being tethered to a machine or bound by hospital schedules.

The science is still in progress, and hurdles remain. Yet the breakthroughs achieved so far signal a profound shift in how we think about kidney failure: not as a condition to be endured, but as one that can be managed with dignity and autonomy. Achieving this future will require continued investment in research, sustained support from policymakers, and a collective push to prioritize kidney health on a global scale.

For the millions living with kidney disease today and the millions more at risk tomorrow these innovations are more than medical marvels. They are a chance to return to ordinary life, free from the constraints of dialysis, with a treatment that quietly restores what illness has taken away: independence.