Your cart is currently empty!

When Compassion Turned Deadly: Oregon Man’s Fight Against Medieval Disease

Paul Gaylord noticed something wrong with Charlie on a Saturday evening. His smoky grey cat had vanished for two days, roaming somewhere in the rural Oregon terrain at the foot of the Cascade mountains. When Charlie finally appeared on the porch, he couldn’t walk. His face had swollen, and something lodged deep in his throat prevented him from breathing properly. A mouse. Stuck completely in the cat’s mouth.

Gaylord didn’t hesitate. He reached in to pull the rodent free. Charlie, distressed and in pain, bit down on his owner’s finger. After the cat fled under the porch and later emerged in obvious agony, Gaylord made the difficult choice to end Charlie’s suffering. He buried the animal in his yard and went back to his normal routine.

What happened next would change his life forever. An act of kindness toward a dying animal set off a medical nightmare that doctors thought belonged in history books, not modern hospitals.

From Cat Bite to Medical Mystery

Monday morning arrived. Gaylord, a welder from Prineville, headed to work as usual. By mid-morning, something felt terribly wrong. Fever struck without warning. His body temperature climbed fast.

At an emergency care clinic, doctors examined the bite wound and prescribed antibiotics for cat-scratch fever. Standard procedure. Simple diagnosis. Gaylord went home expecting a quick recovery.

He got worse instead. Flu-like symptoms overwhelmed him within days. His skin turned an odd grey color. Pain radiated across his entire body. When delirium set in, his wife Debbie rushed him back to the clinic. Medical staff took one look and called an ambulance. He needed intensive care immediately.

Doctors ran tests and examined his body. What they found under his arms stopped them cold: lymph nodes swollen to the size of lemons. One physician recognized the telltale sign and delivered an impossible diagnosis. Paul Gaylord had contracted bubonic plague.

Racing Against Medieval Disease

“We didn’t even know the plague was around anymore,” said his sister Diana Gaylord. “We thought that was an ancient, ancient disease.”

Most Americans share that belief. Yersinia pestis, the bacterium causing plague, killed between a quarter and a third of Europe’s population during the Middle Ages. Modern medicine has pushed it so far from public consciousness that most people assume it no longer exists.

Yet plague persists in rural areas of the American West. Approximately seven cases occur in the United States each year. Rodents and their fleas carry the disease. Cats and dogs can contract it through contact with infected animals. Humans become victims when bitten by carrier fleas or, as in Gaylord’s case, through direct contact with infected animals.

At 6 am the next morning, medical teams placed Gaylord on a ventilator. An ambulance transferred him to another hospital with better resources. He remembers the ride. After that, nothing.

His body shut down fast. Doctors connected him to full life support. A dialysis machine filtered his blood. His lungs collapsed. At one point, his heart stopped beating entirely.

What made Gaylord’s case extraordinary was the disease progression. Most plague victims develop one form of the illness. Gaylord contracted all three simultaneously: bubonic plague attacked his lymphatic system, pneumonic plague invaded his lungs, and septicaemic plague entered his bloodstream. Medical literature contains few documented cases of anyone surviving all three forms at once.

27 Days Fighting Death

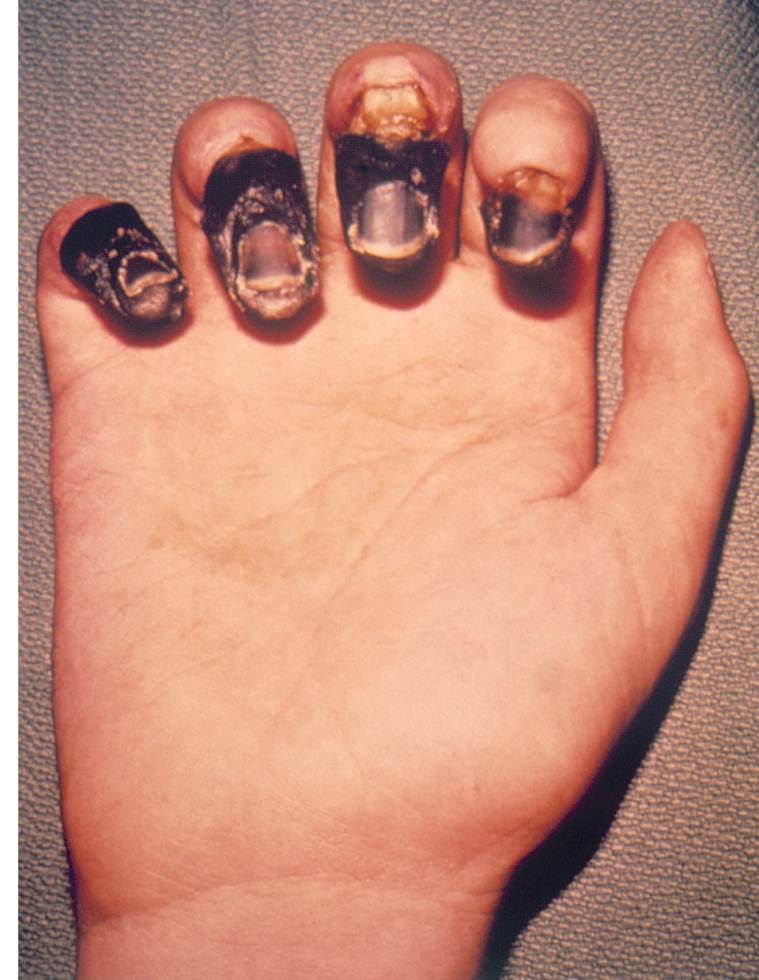

Gaylord slipped into a coma. Days passed. His hands and feet began swelling. As the infection killed cells throughout his extremities, his skin darkened to the color of charcoal. Medical staff watched his fingers and toes die slowly.

His family gathered. After weeks of deterioration, doctors prepared them for the worst. Debbie received the news no spouse wants to hear: they should prepare to say goodbye. A hospital chaplain baptized the unconscious patient. Jake, their son, flew in from Austin, Texas, for a final farewell.

Hours after the family gathered, something changed. Doctors returned with unexpected news. Paul had improved. Against all odds, his body began fighting back.

Waking Up Missing Pieces

When Gaylord finally opened his eyes after 27 days, one thought consumed him: thirst. Extreme, overwhelming thirst. Doctors had performed a tracheotomy and fed him intravenously throughout the coma. He couldn’t drink for days after waking.

“I had collapsed lungs, my heart stopped and my hands and feet turned black. Technically, I shouldn’t be here,” Gaylord later recalled.

Medical staff gradually helped him understand what had happened to his body. Recovery shocked everyone. Doctors had planned to discuss ending life support the day before he woke. His kidneys had failed during the crisis, and staff expected lifetime dialysis. Instead, he needed just one treatment. His internal organs healed completely.

His extremities told a different story. Gaylord spent six weeks at home, living with dead tissue still attached to his body. Doctors needed time to determine which parts might heal before performing amputations. Medical teams initially recommended removing his hands and feet entirely at the wrists and ankles. Gaylord refused. He wanted to keep as much as possible.

Surgeons eventually removed all his fingers but preserved his hands and partial thumbs. All toes on his left foot came off. About a third of his right foot disappeared. Looking at his withered, blackened hands in photos, he faced a hard reality about his future.

How Charlie Brought Home the Black Death

After Gaylord’s diagnosis, the Centers for Disease Control and local health departments launched an investigation. Teams searched his property for dead rodents or signs of plague. Nothing turned up in or around the house.

Officials ordered Charlie’s body exhumed. Samples went to a laboratory in North Carolina for testing. Results confirmed what doctors suspected: the cat had carried plague bacteria. Charlie had picked up infected fleas during his two-day absence, probably from contact with burrowing rodents like mice or squirrels. When Gaylord reached into the dying cat’s mouth, bacteria entered through the bite wound.

Other animals in the area underwent testing. None showed signs of infection. Charlie appeared to be an isolated case, a random intersection of infected wildlife, a wandering pet, and a compassionate owner trying to help.

Building Life After Losing Fingers

Recovery extends beyond physical healing. Gaylord faces ongoing challenges. His immune system, weakened by the illness and months of intensive treatment, remains vulnerable. Yet his living situation poses risks. His manufactured home has a leaky roof, a moldy bathroom, and mice running through it. For someone who nearly died from a rodent-borne disease, these conditions create dangerous exposure.

His family started raising money for safer housing. Medical bills and lost income from his welding career compound their financial stress. At 15 hours a day before his illness, Gaylord’s work ethic had defined his life. Now retired from welding, he struggles with what comes next.

He found one outlet: knife-making. Despite losing his fingers, he can still work in his workshop as a hobby, crafting hunting knives. Small victories matter when rebuilding a life.

Plague in Modern America

Paul Gaylord’s survival makes medical history. Few documented cases exist of anyone contracting all three plague forms simultaneously and living to tell the story. His experience serves as a reminder that diseases from history books still exist in modern America.

Plague bacteria live in rural areas throughout the Western states. Wildlife populations carry it naturally. Most years bring fewer than ten human cases nationwide. People who live in rural regions, especially those with outdoor cats, face the highest risk.

Early recognition saves lives. Symptoms include sudden fever, chills, body aches, and swollen lymph nodes. Anyone developing these symptoms after contact with rodents, dead animals, or animals that hunt rodents should seek immediate medical attention. Doctors can treat plague successfully with antibiotics, but only if they catch it early.

Gaylord wants people to learn from his experience. Rather than dwelling on what he lost, he focuses on awareness. Knowing symptoms and recognizing warning signs gives others a better chance of survival if the unthinkable happens.

One moment of compassion, one attempt to save a suffering animal, nearly cost him everything. Yet looking back, Gaylord maintains a positive outlook. He survived against impossible odds. He adapted to his new physical limitations. He found ways to keep his hands busy and his mind active.

Some days are harder than others. But every day above ground counts as a victory when you’ve beaten a disease that once wiped out a third of Europe.