Your cart is currently empty!

Depression and Anxiety Might Be Spread Through Kissing

Most of us understand that intimacy comes with a certain degree of vulnerability—emotionally, certainly, and often physically. We know that kissing can transmit colds or viruses, and we accept those risks as part of human connection. But emerging science is beginning to suggest that what we pass between each other through close contact might go even deeper, touching the very foundations of our mental wellbeing. A new study out of Iran has raised eyebrows with its provocative findings: that depression and anxiety may not only be influenced by emotional proximity, but also by biological exchange—specifically through the oral microbiome.

Researchers studying newlywed couples observed that when one partner was struggling with mental health symptoms, the other often began experiencing similar issues within just a few months. This wasn’t only a matter of shared stress or cohabiting dynamics—it was accompanied by striking changes in the couples’ microbiomes, especially in the mouth, suggesting a potential microbial pathway for emotional influence. While the science is still evolving and far from definitive, the implications challenge long-held assumptions about how mental health functions within relationships—and how much of our inner world may actually be shaped by those closest to us.

The Unseen Intimacy of Microbes—How Kissing May Influence Mental Health

When we think of the risks associated with kissing, infections like colds, mono, or herpes usually come to mind. However, new research suggests we may need to add mental health issues to the list of possible side effects. A study published in Exploratory Research and Hypothesis in Medicine tracked 268 newlywed couples and found that when one partner reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, or insomnia, the other partner—previously without such issues—began experiencing similar symptoms within six months. Alongside these psychological changes, researchers also noted that the couples’ oral microbiomes had begun to converge, with swabs showing increasingly similar bacterial compositions over time. This alignment in microbial profiles points to the possibility that mental health challenges may be more than emotional—they could also be physiological responses shaped by close personal contact.

The mechanism may lie in cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, which is known to disrupt microbial balance in the mouth. Researchers believe that kissing or other forms of intimate oral contact could facilitate the transmission of stress-altered microbes from one person to another. In the study, certain bacterial groups—including Clostridia, Veillonella, Bacillus, and Lachnospiraceae—were more frequently found in couples affected by these shared symptoms.

These particular microbes have been previously associated with inflammation and mood disorders, suggesting a potential biological pathway for the spread of psychological distress. The findings don’t claim that kissing directly causes mental health problems, but they do indicate that our microbiomes may act as an underrecognized medium through which emotional states and stress-related conditions are partially shared.

The impact appeared especially pronounced among women in the study, whose clinical mental health scores changed significantly in correlation with their partners’ conditions. Their oral bacterial makeup also showed a distinct shift toward the stress-altered profile of their spouse. While the study did not control for all lifestyle factors—such as diet, exercise, or pre-existing conditions—it raises compelling questions about how much of our emotional wellbeing is influenced by those closest to us, not just emotionally but biologically. Intimacy may come with more than shared affection or stress—it may include microbial exchanges that subtly affect mental health in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Why Correlation Is Not Causation

The findings from the study might seem to draw a straight line between sharing microbes and sharing moods, but this is where we need to introduce one of the most important rules in science: correlation is not causation. Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one is responsible for the other. For example, sales of ice cream and the number of people swimming at the beach both go up in the summer, but we wouldn’t say that buying ice cream causes people to go swimming. A third factor—the warm weather—is the real cause of both.

When we apply this lens to the study, the idea that bacteria are the primary culprit begins to look much less certain. There are far more established and scientifically grounded explanations for why a couple’s mental health might synchronize.

First, there is the powerful phenomenon of emotional contagion. Humans are social creatures, hardwired to be attuned to the feelings of those around them, especially their romantic partners. When you live with someone who is struggling with depression, you are intimately exposed to their emotional state. Through empathy, mimicry of their nonverbal cues, and shared daily experiences, it’s a well-documented psychological principle that their feelings can influence your own. The healthy partner’s increased anxiety isn’t necessarily a sign of a microbial infection, but rather a deeply human response to the stress and sadness of a loved one.

Second, the couples in the study were newlyweds, a factor that introduces a host of shared life stressors. The first year of marriage is a period of immense change and adjustment. Merging finances, households, and daily habits is inherently stressful, and this shared pressure alone could easily lead to a convergence of mood. Furthermore, couples who live together eat together. A shared diet is one of the most significant factors in shaping a person’s microbiome. So, the fact that their oral bacteria became more similar is less surprising when you consider they were likely sharing the same meals, snacks, and lifestyle for six months. The microbial shift, in this light, looks less like a cause of distress and more like a biological reflection of a shared life.

The Real Link Between Our Mouths and Our Minds

While the theory of “catching” depression via kissing is shaky, it touches upon a legitimate and fascinating field of science: the connection between our mouths and our minds. Our mouths are home to a vast ecosystem of trillions of bacteria, second only in diversity to our gut. For a long time, we thought this oral microbiome only affected things like cavities and gum disease, but we now know its influence extends throughout the body.

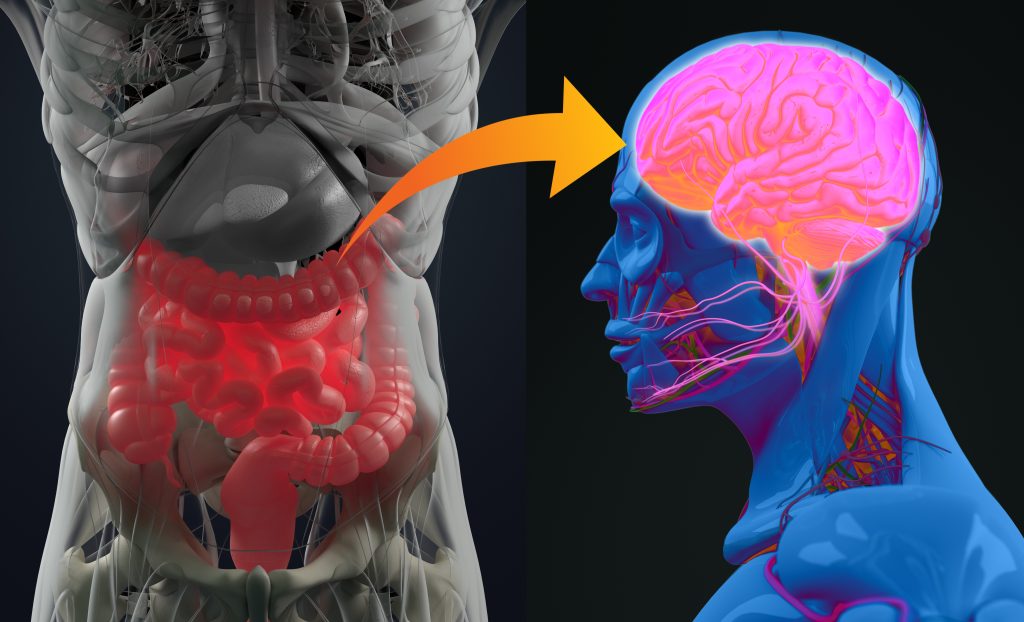

This connection is often called the “oral-brain axis.” The logic is that an imbalance in our oral bacteria, particularly from issues like gum disease, can allow harmful microbes and their inflammatory byproducts to enter the bloodstream. This can create a low-grade, chronic inflammation throughout the body that may eventually impact the brain, a process that has been linked to conditions like depression and anxiety. So, the idea that our oral health can influence our mood is not far-fetched at all.

However, when we look closer at the specific bacteria implicated in the kissing study, the simple narrative of “bad bacteria” being transmitted falls apart. The study reported an increase in four types of bacteria. While some have been associated with inflammation, one of them, Bacillus, stands out for a very different reason. The Bacillus family includes many species that are widely known and sold as beneficial probiotics. In fact, certain strains are considered “psychobiotics” because studies have shown they can help reduce anxiety and depression-like behaviors.

This is a major scientific contradiction. The fact that a well-known beneficial, anxiety-reducing bacterium was found to increase alongside the supposedly “bad” ones undermines the idea that a specific “depressive signature” was being transmitted. It’s much more likely that the study simply captured a general ecological shift in the couples’ mouths—a change driven by a shared diet and stress levels, not the targeted transmission of a mental illness.

Don’t Fear the Kiss: The Proven Power of Physical Affection

Perhaps the greatest irony in this entire discussion is that the very act being painted as a potential risk—kissing—is one of the most well-documented stress relievers available to us. While the theory of microbial transmission is speculative and rests on a single, flawed study, the science on the positive power of physical affection is vast, robust, and conclusive.

When we engage in acts of intimacy like kissing, hugging, and holding hands, our brains respond by releasing a cascade of beneficial chemicals. Levels of oxytocin, often called the “bonding hormone,” rise, fostering feelings of trust, comfort, and connection. At the same time, these actions are known to actively lower cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone.

This creates a direct physiological paradox: for the kissing theory to be true, the supposed negative effect of the transferred bacteria would have to be powerful enough to completely overwhelm the proven, cortisol-lowering benefits of the kiss itself—a highly improbable scenario.

This isn’t just a feel-good theory; it’s a cornerstone of public health wisdom. Major global health bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), consistently emphasize that strong social support, close relationships, and interpersonal connection are among the most powerful protective factors against the development of depression and anxiety. Campaigns like the WHO’s “Depression: let’s talk” highlight that turning toward a trusted person—not away from them—is a critical first step on the path to recovery.

The sensationalist narrative takes the very things known to be an antidote to mental distress—intimacy, affection, and partnership—and attempts to reframe them as the cause. The established science tells us the opposite is true: connection heals.

Shifting from Fear to Mutual Support

The fact that a couple’s moods and even their biology begin to mirror each other over time shouldn’t be a source of fear. Instead, we can see it as profound proof of how deeply our lives are intertwined with those we love. The converging microbes are not a sign of a transmitted illness, but a biological signature of a shared life—shared meals, a shared home, and shared experiences. The synchronizing moods are not evidence of a pathogen, but of empathy, compassion, and the natural human response to a partner’s struggle.

This brings us to the real takeaway, and it is the exact opposite of the one the headlines suggest. Rather than fearing intimacy, we should embrace it as our most powerful tool. The knowledge that our partner’s well-being is so closely linked to our own is not a warning to create distance, but a call to draw closer.

If your partner is struggling, the answer is not to pull away in fear. It is to lean in with support. It is to foster open and honest conversations about mental health, to tackle challenges as a team, and to see their struggle not as a threat to your own health, but as a shared journey that requires your empathy. In times of distress, a loving partner’s touch isn’t a risk to be managed; it is a fundamental part of the healing process. The data is clear: connection is the cure, not the cause.