Your cart is currently empty!

Dolphins Found with Alzheimer’s-Like Brain Damage Spark Urgent Warning for Humans

When scientists discovered dolphins stranded along Florida’s coastlines, they expected the usual signs of environmental distress, perhaps the aftermath of pollution or changing ocean temperatures. What they uncovered, however, has stunned researchers and sparked a wider alarm. Inside the brains of these dolphins were signs of neurological decay strikingly similar to Alzheimer’s disease in humans. The discovery, born from meticulous scientific investigation, has raised profound questions about what our oceans are telling us and what it could mean for human health. These dolphins, once symbols of intelligence and vitality, are now harbingers of something deeply unsettling taking place beneath the waves.

Dolphins as Sentinels of a Changing Ocean

For decades, dolphins have been regarded as sentinels of marine health, living indicators that reflect the condition of the ecosystems they inhabit. When dolphins begin to suffer, it often signals widespread ecological imbalance. Along Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, an estuary famed for its biodiversity but increasingly scarred by agricultural runoff and rising water temperatures, scientists began noticing a heartbreaking pattern. Dolphins were washing ashore, disoriented and sick, their once-lively movements replaced by confusion and distress. Beneath the surface of these tranquil waters lay an unfolding ecological crisis.

Researchers from the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine and the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute began to study the phenomenon in detail. Their investigations revealed extremely high concentrations of toxins produced by cyanobacteria, a type of blue-green algae that thrives in nutrient-rich, warm waters. The discovery connected the dolphins’ neurological damage to a type of toxin capable of attacking brain tissue. The similarities between the dolphins’ brains and those of humans suffering from Alzheimer’s disease were too significant to ignore. The findings shook both the marine science and medical communities, prompting urgent discussions about how environmental toxins might also affect human neurological health.

This wasn’t merely an isolated case of marine poisoning. The dolphins’ condition spoke to a larger truth about the human impact on the planet. Pollution, climate change, and agricultural runoff have transformed once-healthy ecosystems into reservoirs of invisible poison. These dolphins, often called “canaries of the sea,” may well be the first visible victims of a process that could soon reach far beyond the water’s edge.

The Toxin Behind the Brain Damage

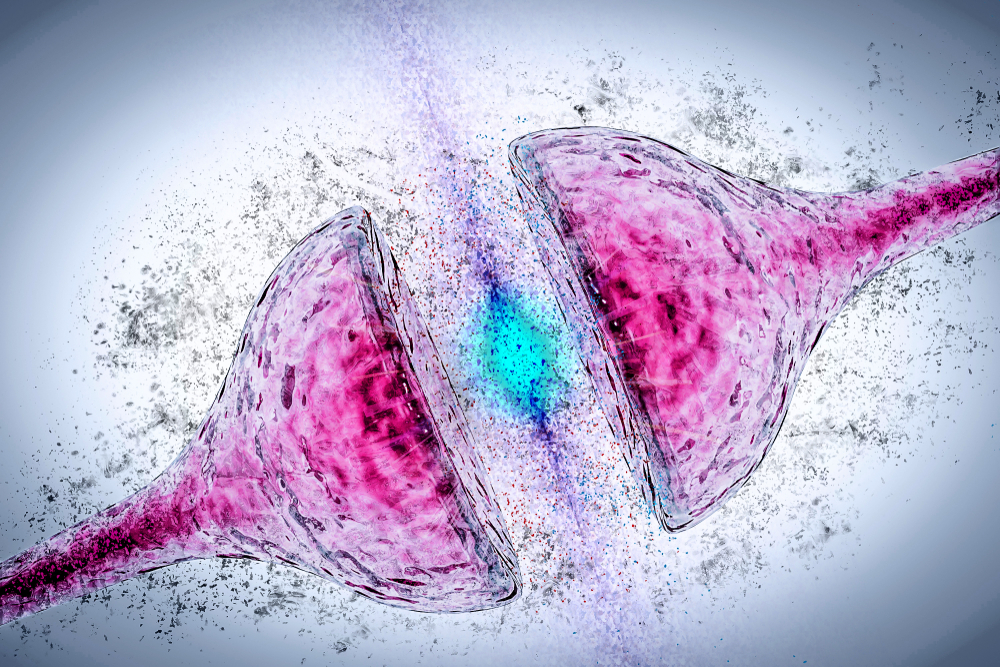

At the center of this discovery is a group of compounds produced by cyanobacteria, particularly a neurotoxin known as beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine, or BMAA. Alongside related toxins such as 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (2,4-DAB) and N-2-aminoethylglycine (AEG), BMAA can be devastating to nerve cells. These substances form during algal blooms, which are massive outbreaks of cyanobacteria that turn rivers, lakes, and coastlines a luminous green. What might look from afar like harmless discoloration of the water is in fact a chemical assault that can destroy entire food chains.

When dolphins swim through these waters or feed on contaminated fish, they absorb high concentrations of these toxins. Researchers examining dolphins stranded along Florida’s coast found that animals exposed during peak bloom periods had up to 2,900 times more 2,4-DAB in their brains than those stranded at other times of year. Under the microscope, the results were deeply troubling. The dolphins’ brains showed sticky amyloid plaques, misfolded tau proteins, and tangled neural fibers — the very same biological signatures that define Alzheimer’s disease in humans.

Dr. David Davis from the University of Miami emphasized the broader implications of the findings. He explained that dolphins are considered environmental sentinels, meaning their health often mirrors human exposure to toxins in shared environments. If these toxins are damaging dolphins’ brains, it stands to reason that humans, who drink, swim, and fish in the same waters, may also be at risk. The discovery underscored how profoundly intertwined our fates are with the natural world.

A Mirror to Human Vulnerability

The alarming truth is that the same toxins poisoning dolphins are present in waters used daily by humans. In Florida and other coastal regions, exposure to cyanobacteria can occur through swimming, fishing, or simply breathing air near affected waterways. Cyanobacterial blooms release airborne particles that can travel inland, settling invisibly into lungs and water supplies. In Miami-Dade County, where Alzheimer’s disease now has the highest prevalence in the nation, scientists are asking whether there could be a connection between long-term exposure to these toxins and the rise in neurodegenerative disease.

Researchers caution that Alzheimer’s disease has many causes, including genetics, age, and lifestyle, but they increasingly suspect environmental triggers play a larger role than once thought. In Guam, scientists studying populations who consumed food contaminated with cyanobacterial toxins found similar patterns of brain degeneration. Laboratory studies have reinforced these observations, showing that prolonged exposure to BMAA can produce the same kind of brain lesions and memory impairment seen in Alzheimer’s patients. This growing body of evidence points to an unsettling conclusion — that the damage visible in dolphins may mirror what is happening, more quietly, within us.

The problem is further complicated by the way these toxins persist in nature. Once they enter the food chain, they tend to accumulate, concentrating as they move from smaller organisms to larger predators. Dolphins, being at the top of their food web, experience the highest exposure levels. Humans, too, may be accumulating small but meaningful doses over time through seafood consumption and water exposure. The dolphins’ suffering, then, may represent a grim preview of the long-term consequences of our environmental neglect.

Climate Change and the Rise of Toxic Blooms

Cyanobacterial blooms are not a new phenomenon, but climate change has supercharged their spread and intensity. Warmer ocean temperatures, heavier rainfall, and nutrient-rich runoff from agriculture and industry create the perfect conditions for these toxic organisms to thrive. In Florida, water released from Lake Okeechobee into surrounding rivers and lagoons regularly carries high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, feeding massive algal blooms that stretch for miles. These outbreaks turn the water an eerie green and suffocate marine life beneath mats of thick, oxygen-depleting slime.

For dolphins and other marine animals, the consequences are devastating. These intelligent creatures depend on echolocation to navigate and hunt, but neurotoxins disrupt their ability to process sound and spatial awareness. Many of the stranded dolphins were found disoriented, swimming in circles or beaching themselves in confusion. Their decline is not an isolated tragedy — it is part of a broader ecological breakdown. Each bloom is a symptom of a larger imbalance caused by warming seas, over-fertilized lands, and human disregard for natural systems.

The human toll is harder to see but no less real. People living near bloom-prone waters report respiratory problems, skin irritation, and headaches during heavy bloom seasons. More worrying are the potential long-term neurological effects of chronic exposure. Scientists warn that if current trends continue, the frequency and toxicity of cyanobacterial blooms will keep increasing, turning more coastal regions into zones of hidden danger. The crisis unfolding in Florida’s lagoons could be a glimpse of what’s to come for coastlines worldwide.

How Toxins Climb the Food Chain

In nature, toxins rarely stay where they start. Once cyanobacterial compounds enter a water system, they are absorbed by microscopic organisms and small fish. Larger fish eat those smaller ones, and predators like dolphins consume them in turn. This process, called bioaccumulation, concentrates toxins at the top of the food web, where they cause the greatest harm. Dolphins, apex predators of their environment, are the unfortunate endpoint of this chain, bearing the cumulative burden of years of exposure.

Humans are part of the same chain, consuming seafood harvested from affected areas. While regulatory agencies test for certain contaminants, cyanobacterial neurotoxins remain under-monitored, and their slow, subtle effects make them difficult to detect. The potential for long-term harm remains largely unquantified. This gap in understanding highlights a troubling truth: environmental damage is rarely contained. What begins in the water inevitably reaches the dinner table, the lungs, and the bloodstream. The health of the oceans is the health of humanity.

Preventing further harm requires collective effort. Scientists advocate for agricultural reform, improved wastewater treatment, and restoration of wetlands that naturally filter runoff. Individuals can also take small but meaningful actions, such as supporting environmental initiatives, avoiding contact with water during visible blooms, and staying informed about local water quality. Solutions exist, but they require both political will and public awareness to be put into action.

The Dolphins’ Warning

The dolphins of Florida’s Indian River Lagoon have become unwilling messengers, their suffering a direct reflection of humanity’s disregard for environmental balance. Their brains, scarred by toxins we helped create, tell a story of interconnection — one that spans from microscopic algae to human cognition. These findings serve as a reminder that the boundaries between human and ecological health are porous and fragile. When we contaminate the ocean, we are not poisoning some distant, separate world. We are, in essence, poisoning ourselves.

The lesson is both urgent and profound. Protecting our waters is no longer just an act of environmentalism; it is a matter of human survival and mental health. The dolphins’ plight challenges us to reconsider how we treat the planet and the invisible threads that bind all life together. If we listen closely, their message is clear: the health of the sea reflects the health of our minds, and to heal one, we must heal the other.