Your cart is currently empty!

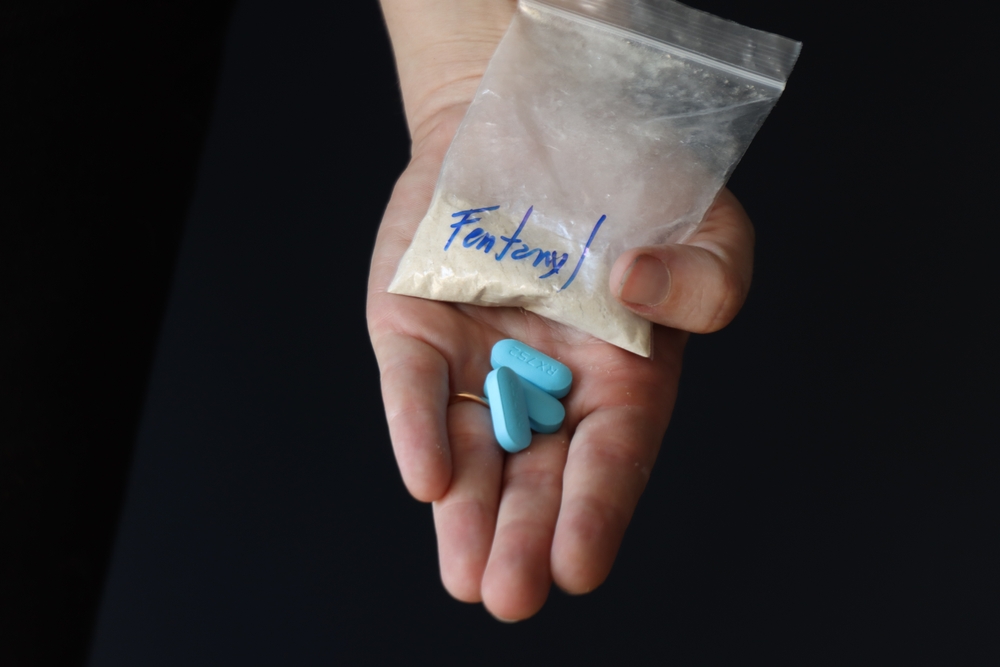

Fentanyl Now Shares a Label with Nuclear Bombs and Nerve Gas

Few executive orders have stretched legal definitions quite like the one President Donald Trump signed on December 15, 2025. With a stroke of his pen, a synthetic opioid joined the ranks of nuclear warheads, nerve gas, and biological agents. Fentanyl, a painkiller used in hospitals worldwide, now carries a label once reserved for weapons capable of annihilating entire cities.

How did a drug end up in the same category as anthrax and sarin gas? And what happens next?

Answers to those questions reveal a collision between public health realities, grieving families, legal boundaries, and military power. Some see the move as long overdue recognition of a crisis that has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans. Others see political theater dressed up as policy. Both sides agree on one thing: nothing about fentanyl will ever look the same.

An Oval Office Announcement

Standing before servicemembers tasked with patrolling the southern border, Trump framed fentanyl as an existential threat to American life. His executive order described the drug as “closer to a chemical weapon than a narcotic,” noting that just two milligrams can kill. An amount equivalent to 10 or 15 grains of table salt separates survival from death.

“We’re formally classifying fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction, which is what it is,” Trump declared. “They’re trying to drug out our country.”

His order blamed Mexican cartels and foreign criminal networks for flooding American streets with the synthetic opioid. It pointed to China as the source of precursor chemicals. And it opened doors for agencies across the federal government to treat drug trafficking as something closer to warfare.

Numbers Behind the Crisis

Trump justified the designation by claiming that 200,000 to 300,000 Americans die annually from fentanyl. Reality paints a different picture, though still a grim one.

Synthetic opioids killed roughly 75,000 people in 2022, when overall drug deaths peaked at about 110,000. By April 2025, annual deaths from synthetic opioids other than methadone had fallen to approximately 42,000. Public health officials credit increased access to overdose reversal medications, expanded addiction treatment, and law enforcement pressure on suppliers for the decline.

A White House spokeswoman pushed back against any suggestion that falling numbers diminish the crisis. Any American death is one too many, she argued, and families who have lost loved ones would agree. President Trump remains committed to fighting illicit fentanyl through every available channel, she said, including its designation as a weapon of mass destruction.

What Federal Agencies Must Do

Beyond rhetoric, the executive order sets specific mandates in motion. Attorney General offices must pursue criminal investigations and prosecutions against trafficking networks with renewed intensity. Sentencing enhancements and variances give prosecutors additional leverage against defendants.

State Department and Treasury officials received instructions to target financial institutions and assets connected to fentanyl production and distribution. Anyone supporting the manufacture or sale of illicit fentanyl and its precursor chemicals now faces potential sanctions.

Perhaps most significantly, the Defense Department must assess whether military resources should flow toward federal law enforcement efforts. Homeland Security received orders to identify threat networks using intelligence tools normally reserved for countering weapons proliferation.

Does Fentanyl Fit the Definition?

Federal law defines weapons of mass destruction as explosives, toxic chemicals, biological agents, or radioactive devices designed to kill large numbers of people. Nuclear bombs fit. Nerve gas fits. Anthrax fits. Fentanyl presents a more complicated case.

Traditional weapons of mass destruction kill indiscriminately and on a massive scale in single events. Fentanyl deaths happen one by one, often among people who knowingly consume illicit drugs, though many victims believe they are taking something else entirely. Unlike nuclear warheads or weaponized pathogens, fentanyl serves legitimate medical purposes as a painkiller after surgeries and during acute care.

Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution sees the designation as plausible given the staggering death toll. Victims often do not know they have consumed fentanyl, he noted, which introduces an element of indiscriminate harm.

Other experts reject the classification outright. Brendan R. Green, a University of Cincinnati political scientist who specializes in military and nuclear policy, offered a blunt assessment. Given the historical use of the term, he said, “it is not even close to reasonable to call fentanyl a weapon of mass destruction.”

Mark Cancian of the Center for Strategic and International Studies pointed out that Congress had ISIS and al-Qaida in mind when writing laws about weapons of mass destruction. Lawmakers were not thinking about drug cartels, no matter how deadly their products.

One Historical Precedent

Only one documented case exists of fentanyl being deployed as a weapon of war.

In October 2002, Russian military forces pumped a fentanyl-based gas into a Moscow theater where Chechen rebels held hundreds of hostages. More than 100 people died from the agent and from inadequate medical response. Rebels and innocent hostages alike perished.

Trump’s executive order mentions the potential for weaponizing fentanyl as one justification for its new classification. Critics argue that building a national strategy around a single incident from more than two decades ago makes for shaky policy foundations. Regina LaBelle, director of the Addiction and Public Policy Initiative at Georgetown University Law Center, wrote in 2022 that devising an entire approach based on one attack is not sound policymaking.

Grieving Parents Find Validation

For families who have buried children after fentanyl poisoning, the designation offers something beyond policy implications. It offers recognition.

Gregory Swan co-founded Fentanyl Fathers after losing his own child. He visited the Oval Office with other parents earlier in December when Trump signed a bill reauthorizing funding for addiction treatment. Swan mentioned the weapon of mass destruction to Trump during the meeting. The president loved it.

Many parents in the room reject the term overdose for their children’s deaths. They believe their sons and daughters were poisoned, often by drug dealers who laced other substances with fentanyl without warning. The new classification aligns government language with their grief.

“The government is agreeing with these parents, that their children’s murders need to be avenged,” Swan said. “They’re not playing nice in the sandbox anymore.”

In 2022, a bipartisan group of 18 state attorneys general urged the Biden administration to declare fentanyl a weapon of mass destruction. They argued that waiting for a terrorist group to weaponize the drug echoed the reasoning failures that preceded September 11, 2001. Trump finally delivered what those officials requested.

Military Strikes Already Underway

Since early September, the Trump administration has conducted more than 20 strikes on suspected drug vessels in the Caribbean and Pacific waters. More than 80 people have died in these operations.

Most targeted boats carried cocaine rather than fentanyl, according to administration officials. Legal scholars question whether blowing vessels out of the water is lawful when authorities have not confirmed cargo or demonstrated that lethal force was necessary. Stopping the boats, seizing drugs, and questioning those aboard remains an alternative.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll found broad opposition to deadly strikes on suspected drug boats. About one-fifth of Republicans disagreed with the military campaign, joining larger numbers of Democrats and independents.

Threats Against Sovereign Nations

Trump has repeatedly threatened military action on land against Venezuela, Colombia, and Mexico. A sweeping strategy document published last week declared that reasserting American dominance in Latin America would be a foreign policy priority.

Mexico remains the largest source of U.S.-bound illicit fentanyl. Chinese companies supply most precursor chemicals. Venezuela has faced administrative criticism despite weak evidence linking that country to fentanyl trafficking specifically.

International law sets clear boundaries around the use of force. An actual or imminent armed attack against a nation justifies a military response. Drug trafficking, however deadly its consequences, does not meet that standard.

Anthony Clark Arend, a Georgetown University professor specializing in international law, was direct in his assessment. Bringing drugs to sell in America, as horrible as it may be, does not constitute an armed attack under any reasonable reading of those words.

Public Health Worries

Emergency room physicians fear the weapon of mass destruction label will frighten patients away from legitimate fentanyl use.

Ryan Marino, an assistant professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University, sees fentanyl as one of the safest and easiest-to-dose pain medications available. Patients already skeptical of opioids may refuse appropriate pain management because they believe they are being given a true weapon.

The executive order applies only to illicit fentanyl produced and distributed in violation of controlled substance laws. Medical fentanyl administered in hospitals and clinics remains legal and unchanged. Whether that distinction reaches public consciousness is another matter.

Will Deaths Actually Decline?

States and federal agencies have already increased penalties and investigations targeting fentanyl traffickers in recent years. Prosecutors possess extensive tools for dismantling drug organizations. Treatment programs have expanded. Naloxone access has grown.

Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University, called the executive order the “latest episode in drug policy theatrics.” Existing law enforcement, interdiction, and prosecutorial resources are already substantial, he argued.

Whether a new classification changes outcomes on American streets remains uncertain. Critics see symbolism without substance. Supporters see a president willing to fight with every weapon available. Families who have lost children see acknowledgment of their pain.

What happens next depends on how agencies interpret their mandates, how courts evaluate legal boundaries, and whether foreign governments respond to pressure. Fentanyl has a new label. Whether that label saves lives is a question only time can answer.