Your cart is currently empty!

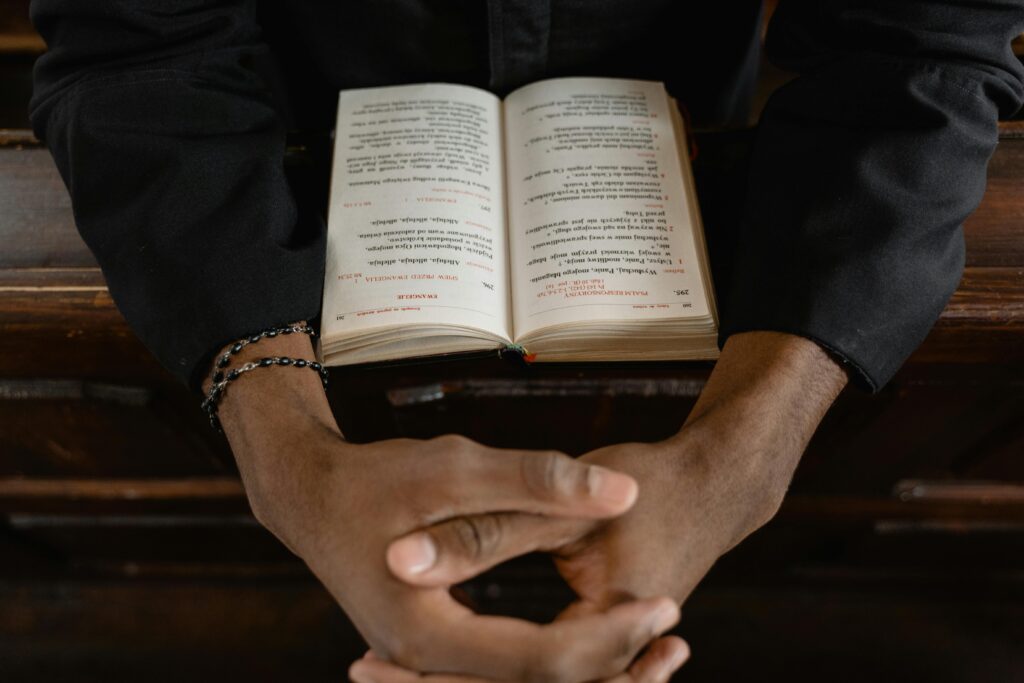

The Teen Who Brought Faith Online and Became a Saint

Carlo Acutis died aged 15, but the fervour around his life and death has made him a global phenomenon: a teenager in jeans and Nike trainers who loved computers, cooked for the homeless, and built an online “museum” of Eucharistic miracles. The story that led to the Vatican’s decision to canonise him two medically inexplicable recoveries attributed to prayers made to him after his death reads like a collision between the ancient rituals of the Church and the viral instincts of the digital age. Pilgrims now queue at his glass tomb in Assisi. His relics travel to churches, and teenagers pose for photos with cardboard cut-outs of his face. The narrative is at once deeply religious and unmistakably contemporary, asking: what does sanctity look like when it wears sneakers and tweets?

Behind the spectacle are human families, doctors, theologians and a Vatican bureaucracy that treats miracles like forensic evidence. Carlo was born in 1991 in London but grew up in Milan, the son of largely secular parents who watched their child choose a life steeped in prayer, charity and a fascination with technology. Diagnosed with leukemia in 2006, Carlo’s short life was marked by intense devotion and small acts of generosity. After his death, reports of sudden recoveries a Brazilian child who could suddenly digest food and a Costa Rican student who recovered from severe head trauma were forwarded to the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints. The dicastery’s secretive medical board, after reviewing scans, medical charts and testimonies, declared both recoveries inexplicable. Those votes cleared Carlo’s path to sainthood, and the Vatican moved with surprising speed. The result: a modern myth stitched from relics, livestreams and two instances of healing that medical panels could not fully explain.

From A Suburban Laptop To A Saint’s Tomb

Carlo’s life reads like a short film script: a bright, slightly introverted boy who loved computers and soccer, who studied catechism and learned to balance homework with daily Mass. He created a website cataloguing Eucharistic miracles accounts where the bread and wine of Communion were said to manifest extraordinary signs and styled it as a digital museum. That project made him a curiosity in church circles: here was a young person who used pixels and servers to spread stories of the sacred. Friends and teachers recalled a kid who, despite living in relative privilege, regularly donated his pocket money and cooked food for the homeless. His mother, Antonia Salzano, and those who knew him emphasise that his faith was not showy; it was practical and focused on small acts of care. When he died in 2006 after a sudden deterioration from leukemia, those habits of devotion and the digital archive he left behind set the stage for a posthumous cult of devotion.

The mechanics of Catholic sainthood are juridical and intensely procedural. After death, a candidate’s life is scrutinised by a postulator who gathers testimonies, examines writings, and compiles a positio, a thick dossier that argues the case. The Dicastery for the Causes of Saints, a Vatican office with its own doctors and theologians, oversees the investigation. Crucially, the Church still requires evidence of supernatural intercession in the form of medically inexplicable healings: one miracle for beatification, a second to move from ‘blessed’ to ‘saint’. For Carlo, those two events, the Brazilian boy’s pancreatic recovery and the Italian student’s neurological restoration, came with clinical records, scans and witness statements. That kind of documentation is what makes modern canonisations feel more like legal adjudication of wonder than spontaneous popular acclaim.

The Miracles: Close Readings And Open Questions

The first reported recovery occurred in Brazil: a toddler named Matheus Vianna suffered from annular pancreas, a congenital condition that made digestion nearly impossible and forced him to rely on liquids and supplements. Family accounts say that after a priest touched a relic of Carlo’s, a piece of his clothing to the child and prayers were said, the boy began to eat and gained weight rapidly. Medical follow-ups, according to Vatican files, showed structural improvements that treating physicians could not explain. The dicastery’s medical board, after requesting and reviewing further documentation, concluded there was no satisfactory scientific explanation for the change. That determination allowed Carlo to be beatified.

The second case is similarly wrenching. A young woman named Valeria suffered catastrophic head trauma in Italy, requiring emergency neurosurgery and showing signs that the prognosis was grim. Her mother prayed at Carlo’s tomb in Assisi; soon after, medical reports recorded a dramatic, lasting recovery that baffled attending specialists. The dicastery’s panel again found the outcome to be without current medical explanation, and the Vatican accepted it as a miracle. These decisions do not claim to prove supernatural causation; canon law instead treats miracles as signs of intercession when no natural explanation appears within the scope of contemporary medical knowledge. Skeptics point to the complexity of medicine and the occasional limits of documentation; believers point to the timing and suddenness of recoveries as suggestive of something beyond clinical probability.

Saints Are Mirrors Of Their Age

Canonisation is both a spiritual declaration and a form of cultural signalling. Historically, saints have reflected what a church and a society value. Medieval saints reflected the struggles of both peasants and nobles, while martyrs embodied political boundaries and confessional identities. Today, the Vatican faced a pastoral problem of how to be heard by younger generations who increasingly live their social lives online. Carlo’s profile, a millennial-born teen who loved computers and used them to extend devotion, offered an attractive bridge. Nicknames like “God’s influencer” and “the patron saint of the internet” are media shorthand, but they point to a substantive appeal: Carlo looks like someone from whose life contemporary young people might borrow language and models for practice.

That selection is strategic and organic at once. The dicastery’s work is not supposed to be marketing, yet the Church is aware that elevating figures who resonate with particular demographics can reanimate devotional life. Carlo’s canonisation thus functions as both pastoral outreach and a cultural mirror. It demonstrates a Church that is aware of social media’s symbolic power and eager to show that holiness can coexist with digital fluency. The irony is delicious: an institution often accused of being archaic using the story of a teenager who made a website to reach the wired generation.

Pilgrimage, Relics And The Economics Of Devotion

After beatification and canonisation, relics frequently travel; the translation of a fragment of a saint’s body or an item of clothing invites direct veneration. Carlo’s relics, pieces of his clothing, a preserved heart fragment in earlier reports, and the silicone mask that helps present his visage to pilgrims became focal points for people seeking tangible contact with the sacred. The Church frames relic veneration as sacramental: objects that, by association with a holy life, become aids to prayer. For parishioners, touching a relic and offering petitions is deeply meaningful. For scholars and critics, relic tours can look like organized pilgrimages that boost attendance and donations to churches.

There are practical and ethical consequences. Shrines draw tourism; Assisi’s sanctuary recorded surges of visitors, and local economies benefit. But the process of documenting miracles which demands medical records privileges those with access to clinical resources. When investigations depend on CT scans and specialist testimony, communities without such infrastructure face obstacles to having their claims reviewed. That asymmetry raises questions about whose experiences of the sacred are legitimized in a formal way. Meanwhile, the postcard imagery of a teen saint in sneakers is potent PR: it makes for arresting photographs that travel well on social media, furthering the saint’s symbolic reach.

Medicine, Mystery And The Limits Of Proof

The dicastery’s medical board operates in a tension between faith and scientific scrutiny. Doctors examine charts, imaging and timelines and ask whether any known medical or surgical intervention could explain a recovery. If no explanation is found in current medical literature and documentation withstands scrutiny, the board may vote to recognise the incidence as inexplicable. That framing differs from an ontological claim of a supernatural cause. It is a negative conclusion that no current natural cause fits the evidence.

This process sits uneasily with scientific framings, which typically hold that unexplained phenomena should be investigated further rather than called miraculous. Medical historians note that what appears inexplicable in one era can become explicable in another; antibiotics or imaging advances have demystified prior medical mysteries. Nonetheless, believers often find meaning in the experience of unexpected recovery and the sanctifying frame the Church provides. For grieving families, the label “miracle” can be a form of narrative closure and a source of comfort. For scientists and skeptics, it is a call to better documentation and continued inquiry.

The Human Cost And Consolation Of Sainthood

Canonisation is an institutional seal on narratives that ordinary people carry in their hearts. The families at the centre of Carlo’s miracles, who testify to sudden recoveries that their doctors could not explain, have been transformed into public voices of gratitude and devotion. Pilgrims who travel to Assisi to kneel before Carlo’s glass tomb bring petitions for illness, bereavement and life-direction. For them, the saint is not an abstract theological object but a present, intercessory figure.

At the same time, the process can be emotionally costly. Postulators and guilds marshal resources, collect testimony and sometimes deal with skepticism from clinicians or community members. The grind of producing a position, coordinating expert testimony and navigating Vatican bureaucracy can be arduous. Yet the payoff recognition, a feast day, global devotion is, for supporters, worth the effort. And for the Church, saints become part of the liturgical calendar, models for imitation and anchors for devotional life.

Legacy of a Millennial Saint

Carlo Acutis’s canonisation blends the ancient with the contemporary, the forensic with the metaphysical. A teenager who uploaded miracles to a website has now become a focal point for pilgrimage, prayer and debate. His story forces us to ask how institutions adapt to cultural change and how people continue to seek the sacred in a world saturated with information and imagery. Some may see Carlo’s sainthood as divinely ordained, others as institutionally useful, and still others as sociologically revealing. In every case, his life and legacy show that humans continue to draw meaning from brief, luminous lives.