Your cart is currently empty!

The Invisible Light of Life and Why It Disappears at Death

Life has always been entwined with the imagery of light. From the fireflies that dance in the night sky to the fiery ball of energy that powers our days, light has symbolized warmth, growth, and vitality for as long as humans have sought metaphors to describe existence. Yet, as science has now confirmed, this connection is more than poetic. Every living being from the smallest bacteria to towering trees and from mice in laboratory cages to humans going about their daily lives emits an invisible radiance.

Known as ultra‑weak photon emission (UPE), this light is so faint that no unaided eye could ever perceive it. Still, it is real, measurable, and universal. Researchers equipped with ultra‑sensitive cameras have captured this glow flickering within cells as they carry out their metabolic duties, only to watch it fade to darkness after death. What you see is neither mysticism nor metaphor. It is simply the physics and chemistry of life showing themselves as light.

The implications of this discovery ripple outward in fascinating ways. At its most profound, it reshapes our understanding of what it means to be alive. Vitality, it turns out, is literally luminous. But the implications are not just philosophical. Scientists envision a future in which this subtle glow becomes a powerful diagnostic tool for medicine, a beacon of crop health for farmers, and a real‑time stress monitor for ecosystems under threat from climate change. That convergence of science, environmental monitoring, and human reflection makes the study of UPE a crossroads of disciplines. It is both a fresh lens through which to view the fragility of life and a practical tool with potential to help us protect it. To appreciate its full significance, we need to explore what UPE actually is, how it has been measured, what the experiments reveal, and what it may mean for the future of medicine, agriculture, and our stewardship of the planet.

What Is UPE (Ultra‑Weak Photon Emission)?

UPE is not to be confused with bioluminescence, the dramatic visible glow that lights up the bodies of fireflies, deep‑sea fish, or glow‑worms. Unlike those evolutionary special effects, UPE is extraordinarily so faint that researchers estimate it amounts to only 10 to 1,000 photons per square centimeter per second. For perspective, a simple household light bulb emits billions of photons in that same span of time. The reason we cannot see UPE with the naked eye is that it falls far below the threshold of our visual system. Yet invisibility does not mean nonexistence. Sensitive cameras designed to count individual photons in total darkness can reveal the shimmer that accompanies the activity of living cells.

The source of UPE lies in oxidative metabolism, the same process by which our cells generate energy. Within the mitochondria, the tiny organelles often described as a cellular power plant, sugars and oxygen are combined to produce ATP, the molecule that fuels everything from muscle contraction to thought. But like any combustion engine, metabolism produces byproducts.

One of these is reactive oxygen species (ROS), chemically reactive molecules that can excite electrons into unstable, high‑energy states. When those electrons fall back to stability, they release energy in the form of photons, the basic units of light. Multiply these microscopic sparks across the billions of cells in a body, and you get a constant shimmer of light too weak for eyes but bright enough for sensitive detectors. In that sense, every living creature is a quiet constellation.

Scientists isolate this glow by placing organisms in shielded enclosures that eliminate ambient light. Cameras like EMCCD and CCD systems are cooled to minimize thermal noise and tuned to capture faint bursts of photons. What emerges in those conditions is an astonishing sight: images of living mice glowing faintly around their organs, or plant leaves shining brighter at the site of a cut or chemical injury. These experiments confirm that UPE is not random static but an authentic signal of metabolic processes in motion.

What The Experiments Actually Showed

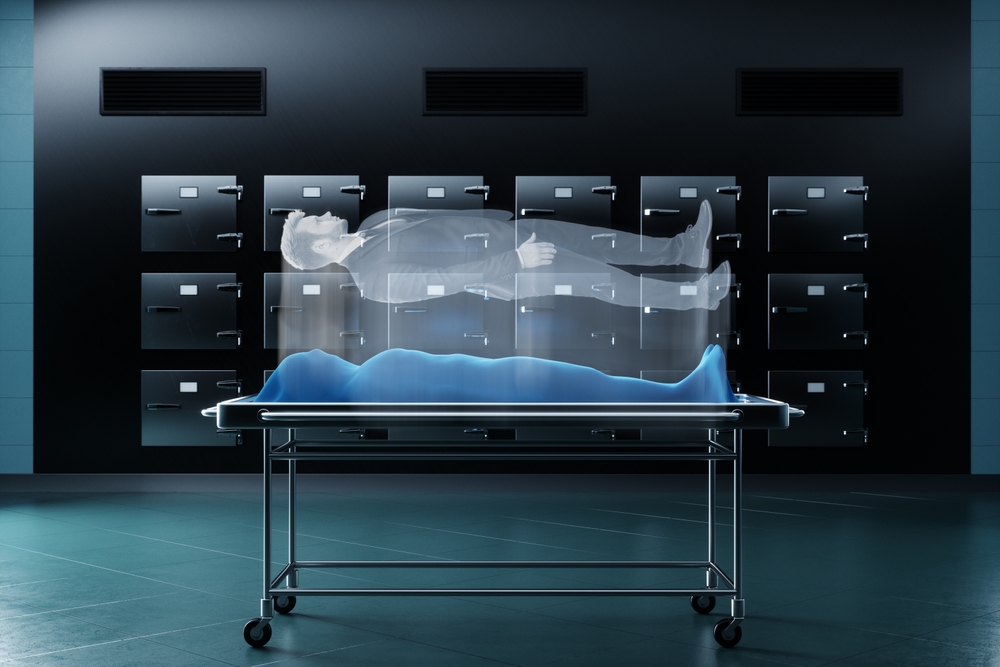

The most compelling evidence comes from controlled experiments comparing living and recently deceased organisms. In one set of studies, researchers placed mice in light‑sealed boxes equipped with photon‑sensitive cameras. While alive, the mice displayed steady emission, with hotspots visible around metabolically active regions such as the paws, skin, and internal organs. After humane euthanasia, however, a dramatic shift occurred. Over the course of thirty to sixty minutes, photon emissions plummeted. Bright regions dulled, scattered points vanished, and eventually the entire glow extinguished. Importantly, researchers maintained the bodies at living temperature to rule out heat radiation as a cause. The decline in light corresponded not to cooling but to the cessation of metabolism. In simple terms, the glow marked life, and its disappearance marked death.

Plants displayed equally revealing patterns. When researchers cut into leaves, exposed them to chemicals, or subjected them to heat stress, photon emissions intensified dramatically at the site of damage. These flashes corresponded to surges in ROS production, a kind of cellular alarm system that plants deploy under duress. In some cases, numbing agents such as benzocaine caused even more photon release than harsher chemical treatments, suggesting that plants respond in complex and not entirely predictable ways. The unifying pattern, however, was clear: healthy tissues glowed faintly, stressed tissues glowed brighter, and dead tissues faded to black.

Such consistency across species underscores the universality of UPE. Whether in animals or plants, the glow is not optional or accidental; it is an intrinsic feature of metabolism. That universality raises tantalizing possibilities. If the glow is tied directly to oxidative processes, then monitoring it could reveal the health and stress status of any living organism. Scientists are only beginning to chart the map of these emissions, but the early contours are already striking.

Why This Matters For Climate, Agriculture, And Ecology

At first glance, UPE may seem like a laboratory curiosity, something scientists get excited about because it looks cool on a screen in the dark. But the practical implications reach far beyond the lab, especially for agriculture and environmental science. The fact that UPE intensifies under stress means it can serve as an early‑warning indicator. In agriculture, farmers spend enormous effort trying to detect plant stress before it damages yield. By the time leaves visibly yellow or wilt, the underlying damage is often already significant. UPE could change that timeline. Because photon emissions increase immediately when oxidative stress rises, farmers might one day use sensors to detect problems hours or days before visible symptoms appear.

Imagine drone swarms flying over large fields at night, scanning for faint photon emissions invisible to humans. Stressed patches could be identified in real time, allowing targeted irrigation, nutrient application, or pest control. Such precision farming would not only improve yields but also reduce unnecessary chemical use, lowering agriculture’s environmental footprint. In a world facing climate change, where droughts, pests, and heat waves threaten food security, early stress detection could be transformative.

Beyond farming, UPE could help ecologists monitor ecosystem health. Forests under heat stress, coral reefs suffering from bleaching events, or wetlands exposed to pollutants may all display altered emission patterns before outward collapse becomes obvious. Just as satellites track chlorophyll fluorescence to assess photosynthetic activity on a planetary scale, future sensors might track biophoton emissions to identify ecosystems in distress. In conservation, where time is always short, that early glimpse into hidden stress could guide interventions.

The potential doesn’t end with plants. Animals, too, emit photon signals linked to stress and metabolism. Monitoring livestock for signs of illness, or even wildlife populations in the field, could one day be possible using UPE technology. In each case, the invisible glow becomes not just a curiosity but a real tool for managing health and sustainability at multiple scales.

Medical And Scientific Applications

One potential application is in organ transplantation. Surgeons must often make rapid judgments about whether a donor organ is viable. If UPE measurements could reveal which tissues are still actively metabolizing, it might reduce the risk of transplant failure. Another possibility lies in pharmacology: testing how cells react to new drugs by monitoring photon emissions could provide early insights into efficacy and toxicity, complementing traditional assays.

The speculative frontier is neuroscience. The brain is the most energy‑hungry organ in the human body, consuming about 20 percent of our oxygen intake. Neurons constantly generate reactive oxygen species as they fire and communicate. Some scientists propose that biophotons might even play a role in brain signaling, forming a kind of light‑based communication network layered atop electrochemical signals. This is far from proven, but if true, it would open extraordinary questions about the role of light in consciousness itself.

Yet even without veering into speculation, the diagnostic promise of UPE is immense. A non‑invasive scan that could track oxidative stress in real time would revolutionize medicine. But getting from laboratory prototypes to everyday clinical use requires surmounting steep hurdles.

Technical And Practical Hurdles

The first obstacle is sensitivity. Photon emissions from living tissues are staggeringly faint. Distinguishing them from background noise whether infrared heat from the body, stray ambient light, or even detector artifacts requires sophisticated isolation. Current experiments rely on complete darkness and expensive, delicate cameras. Scaling that technology into portable devices for hospitals, farms, or field stations is no small feat.

Cost is another challenge. EMCCD cameras, cooling systems, and shielded enclosures are prohibitively expensive for widespread use. Miniaturizing this equipment while keeping noise low will require engineering breakthroughs. Then there is interpretation. Elevated photon emissions signal oxidative stress, but stress can arise from many different sources. A sudden burst could mean a pathogen, physical injury, or normal immune activation. Without careful calibration, UPE data risks being ambiguous.

The temporal dynamics of emissions add another layer of complexity. In mice, photon emissions decline gradually after death rather than vanishing instantly. In plants, stress responses unfold over minutes or hours. For UPE to be useful in practice, researchers will need to build models that translate emission curves into actionable insights. For farmers, that means knowing when to water, fertilize, or treat for pests. For doctors, it means distinguishing between harmless metabolic fluctuations and dangerous disease processes.

How Researchers And Technologists Can Move This Field Forward

To unlock the full potential of UPE, researchers must tackle both technological and conceptual challenges. On the technological side, the development of cheaper, portable single‑photon detectors is essential. Imagine handheld devices or drone‑mounted sensors capable of scanning fields without the need for laboratory‑level shielding. Innovations in photonics, nanotechnology, and signal processing could make that feasible within decades.

Equally important are large datasets. At present, most studies involve small sample sizes and highly controlled conditions. To translate UPE into practical tools, scientists will need vast collections of emission data paired with metadata about environmental conditions, health status, and physiological markers. That data will allow machine learning systems to distinguish between, say, emissions from drought stress and emissions from pest infestation. Standardized protocols across laboratories will also help ensure consistency and comparability.

Applied projects are the final step. Small‑scale pilot programs using UPE sensors in greenhouses, vineyards, or forest plots could provide proof of concept in real‑world conditions. Conservationists might use them to monitor endangered plants, while hospitals could test them as supplements to existing diagnostic scans. Each pilot expands the field’s credibility and practical relevance, moving UPE closer to becoming more than a laboratory curiosity.

A Flicker Of Wonder, A Spark Of Utility

The discovery that living organisms emit ultra‑weak photon emissions is one of those scientific findings that blurs the line between the poetic and the empirical. It tells us something profound: life is luminous, even if that light is too faint for our eyes. It also offers something practical. Researchers see it as a potential tool for detecting stress and disease early in plants, animals, and humans. Between those poles lies a field of research brimming with promise but grounded in hard challenges.

For climate science and ecology, UPE could one day provide early signals of ecosystems under threat, helping us act before damage becomes irreversible. For medicine, it may open new windows into non‑invasive diagnosis. And for philosophy and culture, it offers a striking reminder that the metaphors humans have used for millennia sometimes rest on physical realities waiting to be revealed.

What remains now is not to mystify the glow but to harness it. If we succeed, the faint photons flickering within every living cell may help us understand, preserve, and honor life in ways both practical and profound. The glow may vanish at death, but its discovery could illuminate the way we live and the way we care for our planet.