Your cart is currently empty!

The Methuselah Star Seemingly Predates the Universe, Creating a Major Cosmic Paradox

We intuitively understand that a house cannot be older than the foundation it sits on, yet the cosmos seems to be hiding a contradiction that defies this basic logic. Just 190 light-years away, a star nicknamed “Methuselah” is displaying an age that mathematically exceeds the lifespan of the universe itself. This silent, speeding neighbor in the Milky Way has become one of astronomy’s most frustrating riddles, forcing experts to decide if we are misreading the stars or if the history of everything we know needs to be rewritten.

The Cosmic Chronology Paradox

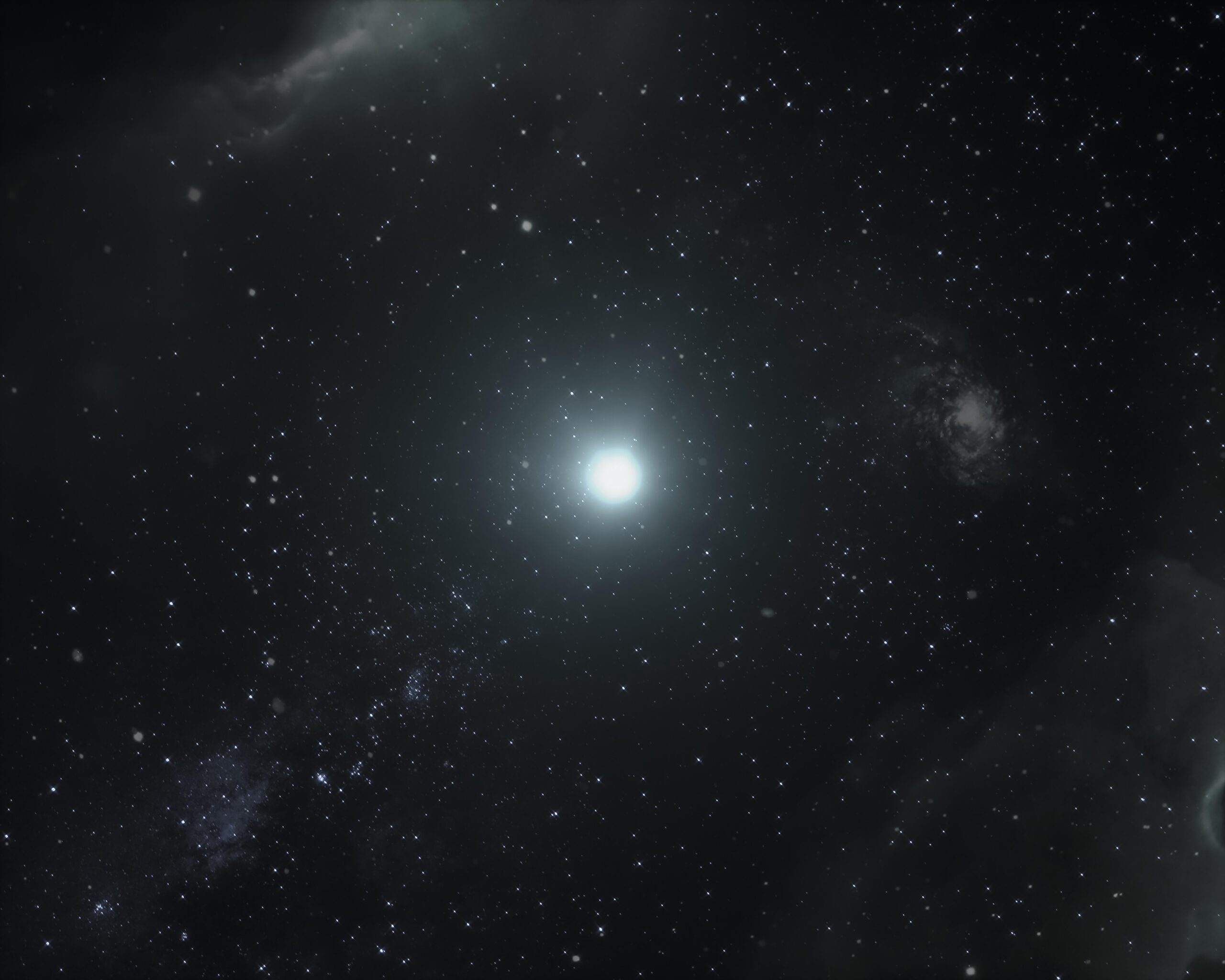

Imagine discovering an antique coin that is dated years before the mint itself was built. This is essentially the puzzle astronomers face with a star officially named HD 140283, but better known as the “Methuselah star.” Located just 190 light-years away in the constellation Libra, this star is speeding across our sky at 800,000 mph. While it might look like a standard point of light to the naked eye, it represents a massive scientific mystery.

Through decades of careful study, scientists have determined that our universe is approximately 13.8 billion years old. This number is considered solid, based on precise data from the Big Bang. However, early observations of Methuselah suggested it was a staggering 16 billion years old. Even after Pennsylvania State University astronomer Howard Bond and his team refined the data, the calculation came out to 14.46 billion years.

This created a confusing situation where a single star appeared to be older than the universe in which it resides. The star is composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, lacking the iron found in younger stars like our sun, which confirms it is incredibly ancient. As Howard Bond noted, the clash between the age of the star and the age of the cosmos was “a serious discrepancy.” This paradox forced experts to ask a difficult question: is our understanding of the star wrong, or is the universe actually older than we think?

How Hubble Solved the Puzzle

To tackle this chronological impossibility, astronomers turned to the Hubble Space Telescope for a closer look. Between 2003 and 2011, Howard Bond and his team utilized Hubble’s Fine Guidance Sensors to measure the star’s distance with unprecedented precision. They relied on a technique called parallax, which observes the shift in a star’s position when viewed six months apart from opposite sides of Earth’s orbit.

Pinpointing the exact distance was vital because it allowed the team to determine the star’s true brightness, or luminosity. As Bond explained, the brighter the intrinsic luminosity, the younger the star actually is.

Beyond distance, the team re-evaluated the star’s internal chemistry. They discovered that Methuselah possessed a higher ratio of oxygen to iron than previously predicted. Furthermore, they updated their models to account for helium diffusing deeper into the star’s core, a process that leaves less hydrogen to burn and effectively speeds up the aging process. These chemical realities meant the star was burning through its life cycle faster than early estimates assumed, suggesting it was not quite as ancient as it first appeared.

These precise adjustments lowered the age estimate to approximately 14.27 billion years. While this figure still sits slightly above the universe’s age, the calculation comes with a margin of error of about 800 million years. This “uncertainty” creates an overlap where the star’s age and the universe’s history finally align.

Physicist Robert Matthews noted that while the best-supported age of the star initially conflicts with the cosmos, the error bars resolve the clash. The star is likely just an extreme senior citizen born very shortly after the Big Bang, rather than a visitor from a time before time.

A New Twist in the Timeline

Just as astronomers felt relieved that the star fits within the universe’s timeline, a new problem emerged. The issue might not be the star at all, but rather how we calculate the age of the universe itself. The accepted age of 13.8 billion years relies heavily on data from the Planck space telescope, which measures ancient radiation left over from the Big Bang. This calculation assumes the universe is expanding at a specific rate.

However, recent studies indicate the universe might be expanding about 10% faster than previously believed. Nobel laureate Adam Riess notes a distinct mismatch between measurements taken from the early universe and observations of nearby galaxies today. This discrepancy is known as the “Hubble Tension.” If the cosmos is indeed expanding faster than the Planck data suggests, it means the universe reached its current size more quickly and is therefore younger than we thought.

A faster expansion rate could drop the universe’s age to 12.7 billion years, while some 2019 calculations suggested it could be as young as 11.4 billion years. If these younger estimates are correct, the Methuselah star is once again mathematically impossible. It would effectively be older than the universe by billions of years, instantly reigniting the paradox that scientists thought they had solved. The mystery has evolved from a question about a single star into a debate about the fundamental physics of reality.

The Dark Energy Variable

The conflict between the age of the Methuselah star and the universe suggests that scientists might be missing a crucial component of the cosmic picture. Physicist Robert Matthews believes the answer lies in greater cosmological refinement. He argues that the discrepancy likely stems from a mix of observational errors and significant gaps in our theory of how the universe evolves.

The primary suspect in this mystery is dark energy. This invisible force makes up about 68% of the universe and is responsible for driving its expansion. Current calculations assume that dark energy has remained constant throughout history. However, if the strength of this force has changed over billions of years, the estimated age of the universe would shift dramatically. Matthews suggests that a “time variation in dark energy” could explain why the universe appears younger than the stars within it.

We also have to consider the overall ingredients of the cosmos. Besides dark energy, the universe consists of about 27% dark matter and less than 5% normal matter. Since the vast majority of the universe is made of invisible substances that physicists are still trying to understand, our standard model of cosmology may be incomplete. This paradox might not be a mistake, but rather a clue pointing toward new physics that we have yet to discover.

Measuring Ripples in Space-Time

To finally settle the debate between the age of the star and the expansion of the universe, astronomers are moving beyond traditional light telescopes. They are turning their attention to gravitational waves. These are ripples in the fabric of space and time caused by massive cosmic events, such as the collision of dead stars. Unlike previous methods that rely on observing light or cosmic radiation, gravitational waves offer a fresh way to measure cosmic distances and expansion rates directly.

Stephen Feeney, an astrophysicist at the Flatiron Institute, suggests that a major breakthrough using this technology could occur within the next decade. The strategy involves analyzing the aftermath of neutron star collisions. By measuring both the visible light and the gravitational waves emitted during these violent smash-ups, scientists hope to calculate exactly how fast these objects are moving away from Earth. This third, independent method could finally tell us which expansion rate is correct without the biases of previous techniques.

Simultaneously, the James Webb Space Telescope is peering deeper into the past than ever before. One of its primary objectives is to locate other ancient, metal-poor stars similar to Methuselah. Finding more of these stellar relics would provide a larger sample size, helping astronomers determine if HD 140283 is a unique anomaly or part of a common population of early stars. These combined technological leaps aim to finally sync our cosmic clocks.

The Gift of Uncertainty

We tend to think of science as a collection of fixed facts, a finished encyclopedia where we can look up the exact age of everything around us. But the “Methuselah star” disrupts that comfort. Its refusal to fit neatly into our timeline is actually a gift. If every observation perfectly matched our expectations, we would have no reason to build the next telescope or question our assumptions about how gravity works. The confusion this star creates is exactly what drives progress.

This paradox highlights a fundamental truth about exploration: being wrong is often more useful than being right. The discrepancy forces astrophysicists to break down their own theories and rebuild them stronger, potentially leading to the discovery of entirely new physics. Whether the answer lies in misunderstood dark energy or a flaw in how we measure light, the search itself pushes the boundaries of human knowledge.

For the rest of us, there is something deeply grounding about a universe that refuses to be easily categorized. Despite our advanced satellites and supercomputers, the cosmos still holds cards it has not played yet. The mystery of HD 140283 is not just a math problem. It is an invitation to keep looking up, reminding us that we are still very much in the early chapters of understanding our place in the stars.