Your cart is currently empty!

Scientists Discover Microplastics in Clouds Are Actively Altering Weather Patterns

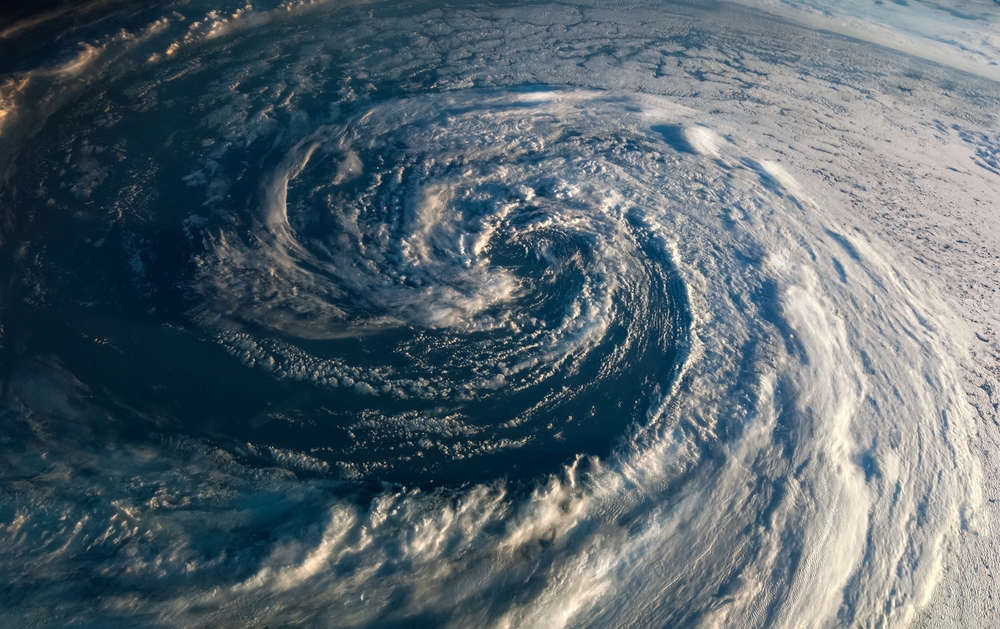

From the depths of the Mariana Trench to the peaks of Mount Everest, plastic pollution has been documented in almost every corner of the planet. Yet, a new frontier has emerged that is far more elusive than land or sea: the atmosphere. Recent research suggests that microscopic plastic particles are no longer just passive litter; they have infiltrated the clouds themselves. This discovery raises unsettling questions about how human debris might be silently rewriting the rules of the weather systems we depend on every day.

The Pervasive Reach of Microplastics

Microplastics have infiltrated nearly every ecosystem on Earth. These tiny particles, smaller than five millimeters, have been discovered in the deepest ocean trenches, atop the highest mountain peaks, and even within human organs. A recent study led by scientists at Pennsylvania State University suggests these synthetic intruders have reached another critical domain: the atmosphere. The research reveals that microplastics are actively influencing cloud formation and could potentially alter global weather patterns.

The study focuses on the ability of microplastics to function as ice nucleating particles. In natural settings, microscopic aerosols such as dust or bacteria usually serve as the foundation for ice crystals to form within clouds. However, this research demonstrates that plastic fragments can perform the same function. Miriam Freedman, a professor of chemistry at Penn State and senior author of the study, highlighted the significance of this finding. She noted that while scientists have found microplastics everywhere over the past two decades, this discovery connects them directly to the climate system. According to Freedman, it is now clear that these particles can trigger the process of cloud formation, necessitating a deeper understanding of their atmospheric interactions.

Testing Common Plastics in the Lab

To understand how these particles behave in the sky, the researchers took their work to the lab. They tested four common types of plastics found in everyday items, including materials often used for grocery bags, packaging, and bottles. The team placed these microscopic bits of plastic into small water droplets and slowly lowered the temperature to see when they would turn to ice.

In a pure environment without any dust or dirt, water droplets in the atmosphere can stay liquid at temperatures far below freezing. Typically, a clean water droplet will not freeze until it reaches about minus 38 degrees Celsius. However, the experiment showed that adding plastic changed this natural rule. The droplets containing microplastics froze at much warmer temperatures, specifically between minus 22 and minus 28 degrees Celsius.

Heidi Busse, the study’s lead author, explained that ice usually needs a solid object to latch onto to start forming. “Any kind of defect in the water droplet, whether that’s dust, bacteria, or microplastics, can give ice something to form… around,” Busse said. By introducing these tiny plastic pieces, the water found a structure to cling to, causing it to freeze much earlier than it would have on its own.

From Microscopic Ice to Major Storms

The ability of these tiny particles to create ice has significant consequences for how clouds behave and how weather develops. When microplastics enter the atmosphere, they do not just sit there; they actively change the recipe for rain. The study suggests that this interference could disrupt standard precipitation patterns, potentially leading to more intense weather events.

Miriam Freedman, who is also affiliated with Penn State’s Department of Meteorology and Atmospheric Science, noted that these particles could alter the timing and intensity of rainfall. In an environment polluted with extra aerosols like microplastics, the water in a cloud must spread out across many more particles. This process creates a high number of very small droplets instead of fewer, larger ones.

Because these smaller droplets are not heavy enough to fall to the ground immediately, the cloud holds onto its moisture for a longer period. The water continues to accumulate overhead rather than releasing gently over time. Freedman explained that this delay results in a specific weather outcome. “Because droplets only rain once they get large enough, you collect more total water in the cloud before the droplets are large enough to fall and, as a result, you get heavier rainfall when it comes.” This implies that microplastic pollution could lead to a cycle of holding patterns followed by heavier, more sudden downpours.

Altering the Atmosphere’s Thermostat

The influence of microplastics extends beyond local rainstorms; it touches the delicate balance of Earth’s climate control system. Clouds play a dual role in regulating planetary temperature. Generally, they act as shields that reflect solar radiation away from the Earth, keeping the surface cool. However, certain clouds at specific altitudes can trap heat emitted from the ground, acting like a blanket and contributing to warming.

Miriam Freedman explained that the specific ratio of liquid water to ice within a cloud helps determine whether it will cool the atmosphere or trap heat. This balance is particularly relevant for “mixed-phase” clouds, which contain a combination of liquid and frozen water. These include common formations such as the puffy cumulus clouds, blanket-like stratus clouds, and the dark nimbus clouds seen during storms. As microplastics accumulate in the sky, they potentially alter this liquid-to-ice ratio, meaning human-made pollution is likely already influencing global temperatures in complex ways.

While modeling the exact long-term outcome remains difficult, the potential shift in how clouds handle light and heat is significant. The introduction of these particles changes the physical properties of the clouds themselves. “We can think about this on many different levels, not just in terms of more powerful storms but also through changes in light scattering, which could have a much larger impact on our climate,” said Busse. This suggests that the microscopic debris floating above us could be tweaking the planet’s thermostat in ways scientists are just beginning to grasp.

How Nature Changes the Plastic

Once microplastics enter the atmosphere, they do not remain static. They are constantly exposed to natural forces such as ultraviolet sunlight, ozone, and atmospheric acids. The researchers investigated how this process, known as environmental aging, alters the way these particles interact with water and ice over time.

To simulate the journey a piece of plastic might take through the sky, the team exposed the test particles to light and chemicals similar to those found in the atmosphere. They discovered that this weathering process significantly changes a particle’s behavior. For three of the plastics tested (LDPE, PP, and PET), exposure to the elements generally reduced their ability to form ice. As these plastics degraded, they became less effective at serving as a nucleus for ice crystals.

However, the results for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) told a different story. The aging process caused physical changes to the surface of the PVC particles that actually increased their potential to form ice. This variation suggests that the impact of microplastic pollution is dynamic rather than fixed. As these particles float through the air and weather over time, their influence on cloud formation evolves. This unpredictability adds another layer of complexity for scientists trying to model the future of our climate, as the behavior of a plastic particle today may differ from its behavior after weeks or months in the sky.

The Price of Convenience

This study forces a hard look at what happens after we throw something away. We tend to think of plastic pollution as something that sits on the ground or floats in the ocean. But knowing these particles are high above us, acting as seeds for ice and rain, changes the stakes completely. It means the waste we generate is not just dirtying the planet; it is actively messing with the weather.

Heidi Busse points out that the “full lifecycle” of these everyday items is likely altering the clouds themselves. This suggests that the convenience of single-use plastic comes with a much higher price tag than previously thought—one paid for in heavier storms and unpredictable climates.

The message here is urgent. We cannot simply recycle our way out of this if the material itself is capable of rewriting atmospheric rules. Reducing plastic consumption is no longer just about saving marine life or cleaning up parks. It is about stopping a man-made variable from destabilizing the skies. If we want a predictable climate, we have to stop feeding the atmosphere the very materials that disrupt it.

Source:

- Wang, Y., Okochi, H., Tani, Y., Hayami, H., Minami, Y., Katsumi, N., Takeuchi, M., Sorimachi, A., Fujii, Y., Kajino, M., Adachi, K., Ishihara, Y., Iwamoto, Y., & Niida, Y. (2023). Airborne hydrophilic microplastics in cloud water at high altitudes and their role in cloud formation. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 21(6), 3055–3062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01626-x