Your cart is currently empty!

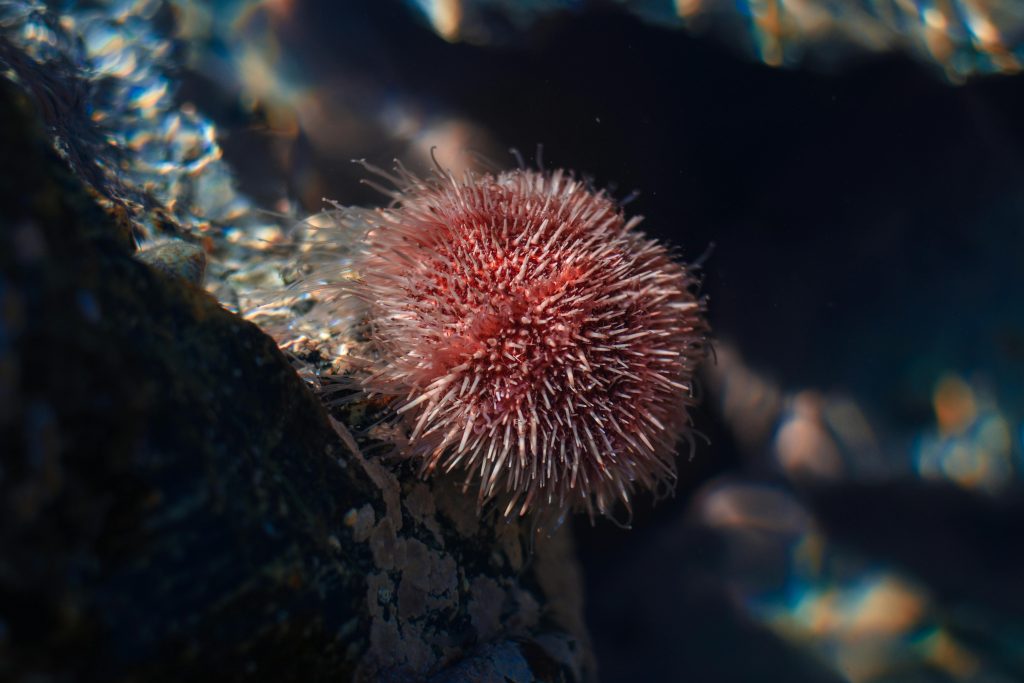

Scientists Uncover the Surprising All Body Brain of Sea Urchins

Sea urchins have long been pictured as simple marine grazers, drifting over rocks and reefs with little more to their biology than a spiny exterior and a slow-moving lifestyle. Yet recent scientific research has brought these quiet ocean dwellers into the spotlight. A series of studies conducted by international teams of developmental biologists and marine researchers has revealed something extraordinary. Sea urchins appear to possess a body-wide nervous system so extensive and sophisticated that some scientists now describe them as all brain.

This revelation challenges long standing assumptions about how nervous systems develop, how evolution shapes sensory abilities and how even seemingly simple creatures can hold unsuspected complexity. It also opens new conversations about the role these animals play in marine ecosystems and what their biology can teach us about environmental change. The following article presents an in depth, neutral and educational exploration of the findings, drawing on multiple recent studies to explain how and why sea urchins defy expectations.

The Transformation From Larva to Adult

One of the most striking aspects of sea urchin biology is the dramatic shift that occurs as they grow from larvae to adults. Sea urchins begin life as small, free swimming larvae that bear little resemblance to the round, spiny creatures that inhabit rocky reefs. These larvae are bilaterally symmetrical. Their bodies can be divided into two mirror image halves, much like humans, fish, insects and countless other animal species.

During metamorphosis, however, the sea urchin undergoes a complete reorganization. The larval form breaks down and is replaced by a radial adult body plan arranged around five repeated segments. This fivefold radial symmetry is a hallmark of echinoderms, the animal group that includes sea stars, brittle stars and sea cucumbers.

For decades, biologists wondered how a single genome could produce two such dramatically different body plans in one lifetime. The larval and adult stages are so distinct that they might almost be mistaken for different species. Recent research on purple sea urchins suggests that many of the answers lie in the reconfiguration of the nervous system during metamorphosis.

When scientists mapped gene activity in young sea urchins shortly after metamorphosis, they found something remarkable. Many genes involved in forming and regulating neurons remained active across development, yet the architecture of the nervous system changed drastically. More than half of all identified cell clusters in the juvenile stage were neurons, indicating a massive expansion of neural tissue.

This finding implies that rather than concentrating their neurons in a single location like a brain, sea urchins distribute them throughout the entire body. The result is a diffuse but highly integrated network that performs many functions typically associated with a centralized brain.

A Body That Functions Like a Head

One of the most surprising discoveries from the recent studies is that sea urchins appear to lack a true trunk region. In most animals, the head and trunk are clearly defined. The head contains the brain and major sensory structures, while the trunk houses internal organs like the stomach, intestines and circulatory systems.

In sea urchins, however, scientists found that genes typically associated with head development in vertebrates are active throughout most of the body. Genes associated with trunk structures appear to be restricted to internal organs such as the digestive system and the water vascular system, a distinctive echinoderm feature used for movement and feeding.

This unusual genetic pattern has led researchers to propose that the entire external body of the sea urchin is essentially head like. If so much of the organism shares developmental similarities with head regions in other animals, it makes sense that its neurons would be widespread rather than concentrated.

This idea reframes how scientists think about echinoderm anatomy. Instead of viewing sea urchins as animals with no head, they can be considered animals that are almost entirely head. Their nervous system follows this same pattern, permeating nearly every region of their anatomy and allowing the creature to sense and respond to the environment in ways that were previously overlooked.

Mapping An All Body Brain

Understanding how such a nervous system functions required detailed investigation of sea urchin cells. Researchers used advanced single cell and gene expression analyses to create cellular atlases of newly metamorphosed sea urchins. These atlases map which genes are active within individual cells, making it possible to identify different cell types and their potential functions.

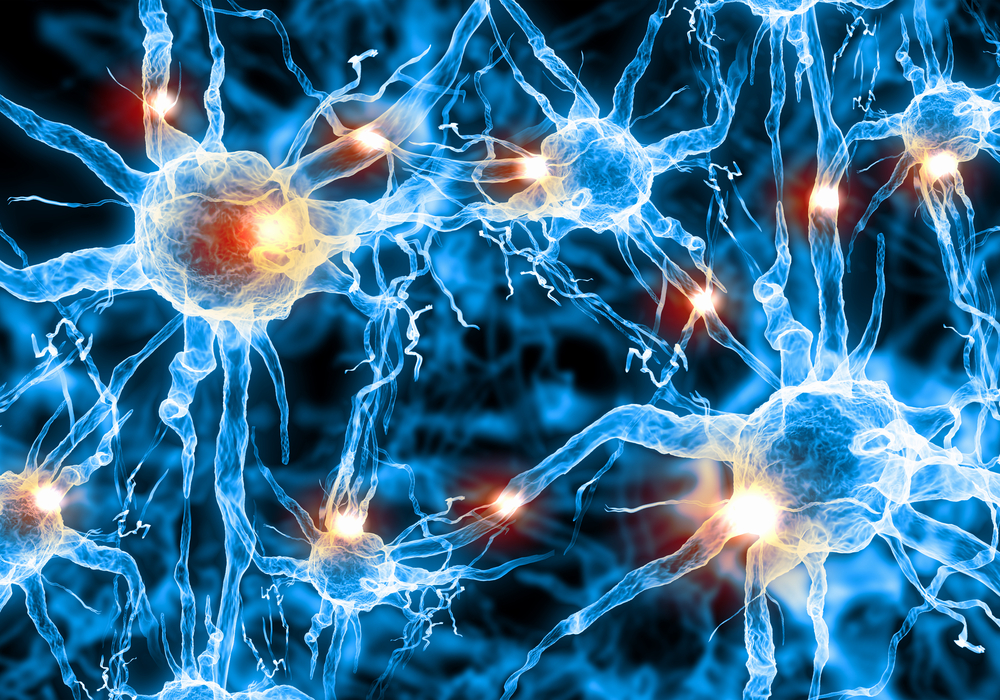

The results were surprising. Instead of a simple nerve net, which had been the traditional assumption for echinoderms, the maps revealed a diverse and highly specialized nervous system. Hundreds of unique neuron types were identified throughout the body. Some expressed genes unique to echinoderms, while others expressed genes found in vertebrate central nervous systems. This suggests deep evolutionary connections between the neural architectures of sea urchins and those of animals with centralized brains.

Even more intriguing was the discovery that many of the neurons expressed familiar neurotransmitters. These included dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, histamine, glutamate and GABA. In vertebrates, these chemicals play a role in mood regulation, coordination, sensory processing and learning. Their presence in sea urchins raises interesting questions about how these animals process information and interact with their environment.

The neurons appear to form an integrated network that covers the entire body. While sea urchins do not possess a brain in the conventional sense, this network functions in a coordinated manner similar to a distributed brain. Instead of a single control center directing responses, neural activity may flow through the entire organism.

Seeing Without Eyes

Another major revelation from recent research is the presence of widespread light sensing cells throughout the sea urchin body. Sea urchins do not have traditional eyes. Yet scientists have long known that they can respond to light, move toward or away from it and adjust their behavior based on environmental brightness.

The new cell mapping studies provide a clearer picture of how this works. Researchers identified numerous photoreceptor cells scattered across the body surface. These cells express opsins, proteins that detect light and convert it into electrical signals. Some cells contained multiple types of opsins, including melanopsin and Go opsin. In humans, melanopsin plays a role in regulating sleep cycles and is found in certain retinal cells.

The distributed nature of these photoreceptors suggests that sea urchins can sense light direction and intensity across their entire bodies. Instead of gathering visual information in a centralized organ like an eye, the sea urchin may interpret environmental light at multiple points simultaneously.

This system may help sea urchins detect predators, navigate rocky reefs or identify safe hiding spots. Because the photoreceptors are integrated into the all body brain, it is possible that light cues influence neural activity throughout the animal. Scientists are still exploring how this integration works and what behaviors it supports.

Implications For Nervous System Evolution

The discovery of the sea urchin all body brain has sparked new discussions about how nervous systems may have evolved. Many evolutionary models suggest that nervous systems tend to become centralized over time. Animals with complex behaviors often rely on a brain to coordinate sensory input and motor responses.

Sea urchins challenge this pattern. They demonstrate that a distributed nervous system can achieve high levels of complexity without forming a single central organ. This raises the possibility that early animals may have had similar body wide neural networks before brains evolved in certain lineages.

If distributed nervous systems were more common in ancient species, then sea urchins may provide a window into early evolutionary stages. Their neural architecture could represent an alternative strategy for processing information, one that relies on coordination across many neural centers rather than a single control hub.

This discovery may also lead scientists to reconsider what it means for an animal to be intelligent or perceptive. Complex processing does not require a centralized brain. Instead, it may emerge from networks where communication flows in multiple directions. Such systems could offer resilience and flexibility, especially in unpredictable environments.

The Role of Sea Urchins in Marine Ecosystems

Although the focus of recent research has been on nervous systems, these findings also highlight the importance of sea urchins within their ecosystems. Sea urchins play vital roles in shaping marine habitats, particularly those involving kelp forests and rocky reefs.

By grazing on algae, sea urchins help control algal growth and can influence the distribution of seaweed species. In balanced ecosystems, this grazing maintains biodiversity and prevents algae from overtaking entire areas. However, when sea urchin populations grow too large, they may overconsume kelp, resulting in what scientists call urchin barrens. These barren zones lack the structural complexity that kelp forests provide, reducing habitat for many marine species.

Understanding how sea urchins sense their environment could help researchers predict changes in their behavior or population dynamics. Climate change affects sea urchin habitats by altering ocean temperatures, acidity and food availability. These shifts may have subtle effects on their nervous system, development and reproductive success. If light plays a major role in sea urchin behavior, then changes in water clarity caused by pollution or sediment disturbances could indirectly influence population trends.

For conservationists and marine managers, this information may prove valuable. Improved knowledge of sea urchin biology can support efforts to protect kelp forests, regulate fisheries and maintain healthy marine ecosystems.

How Light Sensing Shapes Behavior

The discovery that sea urchins possess body wide photoreceptors sheds new light on how they interact with their surroundings. Researchers have observed that sea urchins can move away from bright light or seek shaded areas. Their distributed sensory system might allow them to detect shadows cast by predators or changes in light that signal approaching danger.

Because their nervous system integrates sensory information across the body, sea urchins may process environmental cues in a decentralized way. Instead of sending information to a brain for interpretation, local responses could occur wherever photoreceptors are active. This makes sense for an animal that lacks a distinct head and moves using tube feet spread around its body.

Environmental changes that affect light levels or water clarity could alter how sea urchins navigate and feed. For example, increased sedimentation from coastal development can reduce light penetration. Shifts in water quality might interfere with the signals detected by photoreceptors. Understanding these connections may offer clues about how sea urchins adapt to changing habitats.

A Broader Perspective on Marine Life

One of the most important lessons from the sea urchin research is the reminder that even common, seemingly simple animals may hold extraordinary biological secrets. Marine species often evolve unique adaptations in response to the challenges of underwater environments. These adaptations can provide insight into how life develops, diversifies and thrives.

Sea urchins may become a case study for how organisms use distributed systems to process information. Their biology also highlights the value of studying lesser known marine creatures, not only to understand them better but to broaden scientific perspectives on evolution and ecology.

Environmental changes are impacting oceans around the world. By learning more about the sensory systems and neural architectures of species like sea urchins, scientists gain tools to better predict how marine ecosystems will respond to future pressures.

Appreciating the Complexity Beneath the Surface

The revelation that sea urchins are essentially all brain represents a major shift in how scientists understand nervous system evolution and echinoderm biology. Once thought to possess only a simple nerve net, sea urchins now appear to have an extensive, integrated nervous system capable of sophisticated processing.

Their transformation from bilaterally symmetrical larvae to radially symmetrical adults showcases the remarkable adaptability of their genetic programs. Their body wide neural network and widespread photoreceptors reveal new dimensions of sensory awareness previously unrecognized in these creatures.

As research continues, sea urchins may offer key insights into how distributed nervous systems function, how sensory information can be processed without centralized organs and how animals adapt to diverse environments. These findings encourage a more appreciative view of marine life and remind us that even familiar species may hold surprises that deepen our understanding of the natural world.

By examining creatures like sea urchins with curiosity and care, science continues to uncover the hidden complexities of life beneath the ocean surface.