Your cart is currently empty!

The Geological Secrets Making Greenland Earth’s Most Coveted Island

Somewhere between Iceland and Canada, a massive island holds secrets that could reshape our planet’s future. Most people picture Greenland as an endless expanse of ice and snow, a frozen wilderness at the edge of the world. Few realize what lies beneath that pristine white surface. Fewer still understand why governments, scientists, and mining companies have turned their attention toward one of Earth’s most remote places with increasing urgency.

Jonathan Paul, an associate professor in Earth Science at Royal Holloway, University of London, recently pulled back the curtain on Greenland’s hidden wealth. What he revealed reads like a geological thriller, complete with billion-year-old mysteries, buried treasures, and a modern dilemma that pits our clean energy ambitions against the very environment we hope to protect.

An Island Built on Four Billion Years of History

Greenland earned its title as Earth’s largest island, stretching across more than 2.1 million square kilometers. Yet ice blankets roughly 80 percent of that territory. Only a fraction of its surface, an area nearly double the size of Britain, remains ice-free. What scientists have found in those exposed regions hints at something extraordinary hiding beneath the frozen interior.

Some of the oldest rocks on our planet call Greenland home. Near Nuuk, the capital, formations date back nearly 3.8 billion years, placing them among the most ancient geological features known to science. Truck-sized lumps of native iron, not from meteorites but formed within Earth itself, dot certain regions. Diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes emerged in the 1970s, though the brutal logistics of Arctic mining have kept them largely untouched.

For researchers who study Earth’s deep history, Greenland represents something rare and valuable. According to Paul, the island offers an unusually complete record of how natural resources form. “Geologically speaking, it is highly unusual (and exciting for geologists like me) for one area to have experienced all three key ways that natural resources, from oil and gas to REEs and gems, are generated,” he explains.

How Mountains, Oceans, and Volcanoes Created Hidden Wealth

Understanding Greenland’s riches requires a journey through geological time. Natural resources emerge from three primary processes, and Greenland experienced each one during its long history.

Mountain building came first. Over billions of years, massive compressive forces squeezed and fractured Greenland’s crust during prolonged periods of tectonic activity. As the land buckled and broke, minerals found pathways through the newly formed faults and fractures. Gold settled into these cracks. Rubies followed. Graphite, now essential for lithium battery production, accumulated in deposits that remain largely unexplored compared to those in China and South Korea.

Rifting arrived next, bringing a different kind of wealth. When continental crust relaxes and stretches apart, sedimentary basins form in the resulting depressions. Greenland’s most significant rifting event began just over 200 million years ago, when the Atlantic Ocean started forming during the Jurassic Period. Sedimentary basins like Jameson Land now hold what geologists believe could rival Norway’s hydrocarbon-rich continental shelf. Estimates from the US Geological Survey suggest that onshore northeast Greenland, including areas still buried under ice, contains around 31 billion barrels of oil-equivalent in hydrocarbons. For perspective, that figure matches the entire proven crude oil reserves of the United States.

Lead, copper, iron, and zinc also appear in these sedimentary formations. Small-scale mining operations have worked some deposits since 1780, though commercial exploration has remained limited by prohibitive costs.

Volcanic activity added the final layer of mineral wealth. While Iceland, Greenland’s neighbor, sits directly atop a volcanic hotspot, Greenland’s own volcanic history left lasting gifts. Rare earth elements, including niobium, tantalum, and ytterbium, accumulated in igneous rock layers formed by ancient eruptions. Warm hydrothermal waters circulating near volcanic intrusions carried these valuable elements upward, depositing them in concentrations that modern industry desperately needs.

Rare Earths and the Clean Energy Equation

Among Greenland’s buried treasures, rare earth elements generate the most excitement and controversy. Modern technology depends on these materials in ways most consumers never consider. Wind turbines require them. Electric vehicle motors cannot function without them. Nuclear reactors use magnets containing rare earths to operate in high-temperature environments.

Two elements stand out for their importance and scarcity. Dysprosium and neodymium rank among the most economically valuable yet difficult-to-source rare earth elements on the planet. Greenland may hold sub-ice reserves of these materials sufficient to satisfy more than a quarter of predicted future global demand. Combined estimates approach nearly 40 million tonnes.

Known deposits like Kvanefield in southern Greenland could reshape global rare earth markets if developed. Yet similar deposits almost certainly exist in the island’s central rocky core, still buried and undiscovered beneath kilometers of ice. Given how scarce these elements remain worldwide, even modest Greenland production could send ripples through supply chains that currently depend heavily on a handful of producing nations.

A Paradox Written in Melting Ice

Climate change has created a troubling paradox for Greenland and the world. An area equivalent to Albania has melted away since 1995, and scientists expect the trend to accelerate unless global carbon emissions decline sharply. As ice retreats, previously inaccessible resources become available for extraction.

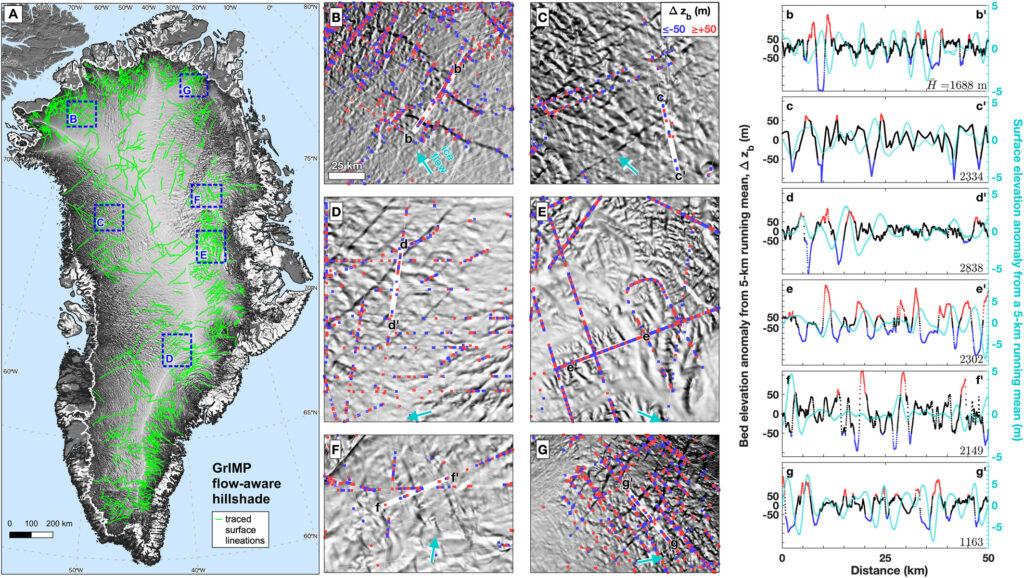

Advanced survey techniques now allow researchers to peer beneath the remaining ice cover with increasing precision. Ground-penetrating radar can map bedrock topography through up to two kilometers of frozen barrier, offering clues about potential mineral resources hiding below. Progress in prospecting under ice remains slow, however, and sustainable extraction will prove even harder to achieve.

Despite the island’s potential, actual mining operations have remained surprisingly modest. A 2020 study on Arctic mining in Greenland noted this gap between promise and reality. “Mining activities have so far been limited in Greenland, considering the potential. A relatively weak record of mining activity appears to contrast with the metal endowment and existence of numerous mineral occurrences and several world-class mineral deposits.”

Remoteness explains part of the disconnect. No roads connect Greenland’s towns and settlements, forcing reliance on helicopters, boats, and aircraft for transportation. Harsh Arctic conditions multiply costs and complications. Any mining operation must supply its own energy, water, and communication infrastructure from scratch.

Extraction Versus Protection

Greenland now faces a question that extends far beyond its shores. Paul frames the dilemma with uncomfortable clarity. “Should Greenland’s increasingly available resource wealth be extracted with gusto, in order to sustain and enhance the energy transition?”

Both answers carry consequences. Mining Greenland’s resources could accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels by supplying materials essential for batteries, turbines, and electric motors. Yet extraction would add to the environmental pressures already transforming Greenland and affecting communities worldwide. Pristine landscapes would bear scars from industrial activity. Ice melt contributing to rising sea levels could threaten the very coastal settlements where Greenland’s population lives.

Currently, strict legal frameworks dating from the 1970s govern all mining and resource extraction activities. Greenland’s government maintains heavy regulation over the industry, requiring extensive environmental assessments and community consultations before projects advance. Social license to operate generally remains favorable among residents, with surveys showing a majority support for mining development.

International interest may test these regulatory structures in the coming years. American attention toward Greenland has intensified, and pressure to loosen controls or grant new exploration licenses could grow. Denmark, which retains authority over foreign affairs and defense matters, navigates a delicate balance between Greenland’s increasing autonomy and broader geopolitical considerations.

Frozen Fortunes Hang in the Balance

Greenland stands at a crossroads where ancient geology meets modern ambition. Beneath its ice sheet lie materials that could power a cleaner future, locked away by the very frozen barrier that climate change now steadily removes. Each year of melting ice reveals new possibilities while raising fresh questions about cost and consequence.

For geologists like Paul, Greenland offers a laboratory unlike anywhere else on Earth. For policymakers, it presents choices with global implications. For the roughly 56,000 people who call Greenland home, it represents both opportunity and uncertainty as outside interest in their island grows.

What happens next depends on decisions made in Nuuk, Copenhagen, Washington, and boardrooms around the world. Greenland’s resources will not remain hidden forever. Ice continues melting. Technology continues to improve. Demand for rare earths and critical minerals continues climbing.

Whether Greenland’s buried wealth helps solve the climate crisis or deepens it may ultimately depend on how carefully humans approach the dilemma that ice and geology have created together over four billion years.