Your cart is currently empty!

The Mystery Behind Spider Silk’s Strength Is Finally Solved

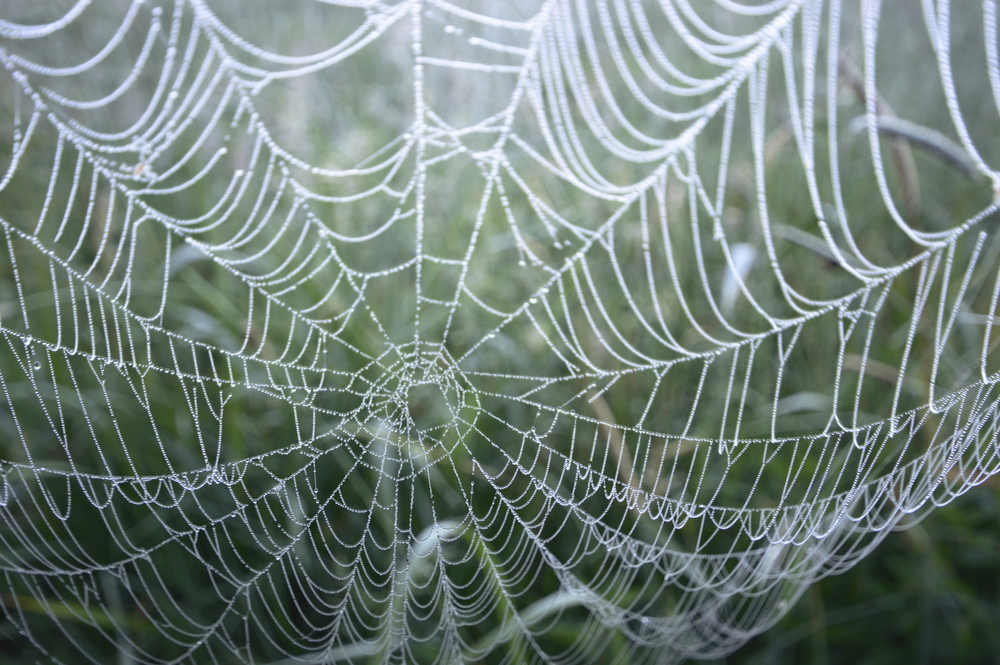

Spider webs might look fragile when they catch the light in the early morning, but their beauty hides one of the most advanced materials ever discovered in nature. For years, scientists have marveled at the fact that spider dragline silk is stronger than steel for its weight and tougher than Kevlar, the material used in bulletproof vests. Engineers have attempted to copy it, chemists have tried to decode it, and material scientists have studied it under powerful microscopes, yet the exact reason behind its remarkable balance of strength and flexibility remained elusive.

Now, researchers say they have finally identified the tiny chemical attractions that allow spider silk to perform its famous balancing act. By understanding what holds the material together at the molecular level, scientists believe they are closer to designing a new generation of high performance, sustainable fibers that could be used in aircraft components, protective clothing, medical implants, and even soft robotics. Unexpectedly, the same discovery may also offer insight into neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s, showing that the secrets woven into a spider’s web could extend far beyond materials science.

The Material That Outperforms Steel

Spider dragline silk is not just strong in a laboratory sense. Pound for pound, it outperforms steel in tensile strength while remaining lightweight and flexible. It can stretch significantly before breaking and absorb enormous amounts of energy without snapping, a combination that engineers typically struggle to achieve in synthetic materials. Most strong materials are rigid and brittle. Most flexible materials sacrifice strength. Spider silk somehow achieves both.

Spiders rely on this extraordinary fiber to construct the structural framework of their webs and to suspend themselves in midair. Every leap, every drop, and every tension bearing strand depends on silk that can withstand sudden forces and sustained loads. If it were to fail easily, spiders would not survive. Evolution has refined this material over millions of years into something remarkably efficient and resilient.

For decades, scientists have tried to replicate spider silk artificially. The challenge has never been recognizing its performance. The challenge has been understanding exactly how nature produces such an exceptional fiber under ordinary environmental conditions without extreme heat, toxic chemicals, or energy intensive processing.

Inside the Spider’s Silk Gland

The story of spider silk begins inside a spider’s silk gland, where proteins are stored in a dense liquid form known as “silk dope.” These proteins are long chains built from amino acids, and in their liquid state they are packed together in a highly concentrated solution. At this stage, the material does not yet resemble a solid fiber. It behaves more like a thick biological fluid.

When a spider begins to spin its web, that liquid is drawn out and transformed into a solid strand. Scientists have known that before the silk hardens, the proteins first gather into liquid like droplets through a process called phase separation. However, the precise molecular steps that connect this early clustering to the final strength of the silk have remained unclear.

The transformation from liquid to solid happens smoothly and rapidly inside the spider’s body. It is a finely tuned process that converts disordered proteins into highly organized structures capable of bearing significant mechanical stress. Understanding how this reorganization occurs has been one of the central puzzles in materials science.

The Tiny Molecular Interactions That Change Everything

In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by researchers from King’s College London and San Diego State University, scientists identified the specific molecular interactions that drive silk formation. Their work revealed that two amino acids, arginine and tyrosine, interact in a way that acts like reversible molecular “stickers,” holding the proteins together as they assemble.

These subtle chemical attractions, known as cation–π interactions, trigger the initial clustering of silk proteins during the liquid phase. Crucially, the same interactions remain active as the silk fiber forms, helping to create the complex nanostructure responsible for its exceptional mechanical performance. Rather than disappearing once the fiber solidifies, they continue guiding how the material organizes at the smallest scales.

Chris Lorenz, Professor of Computational Materials Science at King’s College London, explained the broader significance of the discovery. “The potential applications are vast — lightweight protective clothing, airplane components, biodegradable medical implants, and even soft robotics could benefit from fibres engineered using these natural principles,” he said. He also noted, “This study provides an atomistic-level explanation of how disordered proteins assemble into highly ordered, high-performance structures.”

A Surprisingly Sophisticated Natural Process

One of the most striking aspects of the research was how chemically sophisticated spider silk turned out to be. Many people imagine silk as a simple natural fiber, but at the molecular level it relies on highly specific interactions between amino acids that must occur at the right time and in the right arrangement. The process is precise, controlled, and far more intricate than it appears.

Gregory Holland, an SDSU professor of physical and analytical chemistry who led the US side of the study, admitted the findings challenged assumptions. “What surprised us was that silk — something we usually think of as a beautifully simple natural fiber — actually relies on a very sophisticated molecular trick,” Holland said. “The same kinds of interactions we discovered are used in neurotransmitter receptors and hormone signaling.”

Those comments highlight a deeper realization. The chemistry that allows spiders to spin incredibly strong threads is not isolated to arachnids. Similar molecular principles are at work throughout living systems, including within the human body. That overlap hints at implications that extend beyond engineering.

What Spider Silk Reveals About Alzheimer’s

The researchers also pointed out that the way silk proteins undergo phase separation and then form β-sheet rich structures mirrors mechanisms observed in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. In these diseases, proteins in the brain can misfold, cluster, and reorganize into rigid aggregates that disrupt normal cellular function. The structural similarities are difficult to ignore.

Holland explained the connection more directly. “The way silk proteins undergo phase separation and then form β-sheet–rich structures mirrors mechanisms we see in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s,” he said. “Studying silk gives us a clean, evolutionarily-optimized system to understand how phase separation and β-sheet formation can be controlled.”

In spider silk, the process is tightly regulated and produces a beneficial material with extraordinary properties. In disease, similar structural transitions become harmful. By studying silk as a controlled model system, scientists may gain insight into how to better manage or prevent problematic protein aggregation in human health.

Engineering the Future With Nature’s Blueprint

Rather than attempting to copy spider silk molecule for molecule, researchers are increasingly focused on understanding the fundamental design principles behind it. The discovery of these reversible molecular interactions provides a rulebook that engineers can adapt to create new materials with similar performance characteristics without needing to replicate the exact biological system.

Potential applications span multiple industries. Lightweight protective clothing could become stronger and more comfortable. Aerospace components could be built from materials that reduce overall weight while maintaining structural integrity. Biodegradable medical implants and sutures could combine durability with compatibility inside the human body.

The larger lesson is that evolution has already solved engineering challenges that continue to test modern science. By decoding how simple amino acids interact to form complex, high performance structures, researchers are not just learning how to make stronger fibers. They are learning how to design materials that are efficient, adaptable, and sustainable.

Spider silk may look delicate when stretched between two branches, but its molecular architecture tells a different story. Hidden within those nearly invisible threads is a blueprint that could shape the future of materials science and deepen our understanding of the human brain. Sometimes the most transformative discoveries are woven into places we have overlooked for centuries.