Your cart is currently empty!

Where Does Oil Actually Come From? The Answer Isn’t Dinosaurs

Picture yourself at a gas station, pumping fuel into your car. You might imagine, somewhere in the back of your mind, that you’re filling your tank with liquefied velociraptor. Maybe a hint of T. rex. Perhaps some stegosaurus for good measure.

Sounds absurd when you say it out loud, doesn’t it? Yet millions of people believe exactly that. Ask someone where oil comes from, and chances are they’ll mention dinosaurs without hesitation. It’s one of those facts that everyone seems to know, passed down through generations like a game of telephone that nobody bothered to fact-check.

Here’s the problem with that cozy little story about dinosaur soup powering our vehicles. It’s wrong. Completely, entirely, scientifically wrong. And according to geologists who actually study these things for a living, it’s time we set the record straight.

What Really Powers Your Morning Commute

Reidar Müller, a geologist from the University of Oslo, has made it his mission to kill this myth once and for all. He’s tired of hearing it repeated at dinner parties, seeing it in children’s books, and watching it spread across social media like wildfire.

“For some strange reason, the idea that oil comes from dinosaurs has stuck with many people,” Müller told Science Norway. “But oil comes from trillions of tiny algae and plankton.”

Wait. Algae? Plankton? You mean those microscopic things floating around in the ocean that whales eat? Yes, exactly those things. While dinosaurs were stomping around on land, being huge and impressive, something far less glamorous was happening in the oceans. Tiny organisms were living, dying, and preparing to become the most valuable substance on Earth tens of millions of years later.

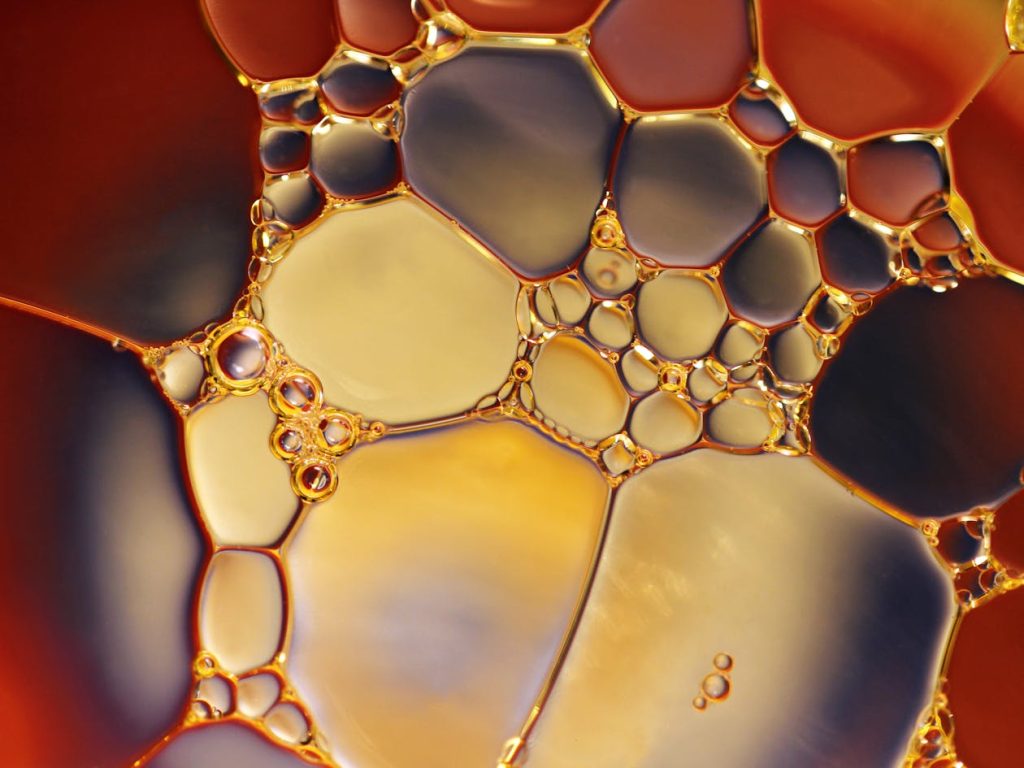

When these microscopic creatures died, they didn’t simply disappear. Algae and plankton sank slowly through the water column, drifting down to the seafloor like an endless rain of organic matter. They accumulated there, piling up in layers, getting buried under more dead organisms, then sediment, then more sediment, then more still.

Years passed. Millennia. Millions of years. Slowly, inexorably, the weight of all that accumulating material pressed down on those ancient organic remains. Pressure mounted. Temperatures rose as the layers sank deeper into the Earth’s crust, reaching between 60 and 120 degrees Celsius. Oxygen disappeared from the equation.

And then something remarkable happened. Under those extreme conditions, the organic matter cooked. Chemical bonds broke and reformed. Molecules rearranged themselves. Over geological timescales, trillions upon trillions of tiny dead organisms transformed into something entirely different. Something thick, black, and energy-dense.

Oil.

Once formed, the oil didn’t just sit there politely waiting for humans to invent drilling technology. It moved. Being less dense than the surrounding rock, it seeped upward through porous layers, flowing like an underground river in slow motion. It traveled upward until it encountered something it couldn’t penetrate: a dense rock layer that acted like a lid. Trapped beneath this impermeable barrier, the oil pooled and waited. Sometimes for millions of years. Sometimes, until an oil company came along with a drill bit.

So Where Do Dinosaurs Fit Into All of This?

They don’t. Not really. Sure, when a marine dinosaur died, or when some unfortunate land-dwelling dinosaur discovered too late that its arms weren’t designed for swimming, it would end up on the ocean floor. But that’s where the similarity to oil formation ends.

Here’s why dinosaurs never made it into your gas tank. When a large animal dies in the ocean, it doesn’t get to lie there peacefully decomposing under layers of sediment. It becomes lunch. Scavengers arrive. Fish pick at the flesh. Crustaceans clean the bones. Bacteria break down what’s left. Long before that dinosaur could be buried deep enough to start the oil-formation process, it would be scattered across the seafloor in fragments, consumed by the food chain.

Remember that oxygen-deprived environment we mentioned? You need that for oil formation. Living things need oxygen. Where there’s oxygen, there’s life. Where there’s life, creatures are eating dead things before they can turn into fossil fuels. Dinosaurs, being large and meaty, would have attracted quite the buffet line of hungry ocean dwellers.

Müller does acknowledge one tiny exception. A single dinosaur bone was once found in an oil well in Norway. One bone. In all the oil ever drilled. Scientists have also found skeletons of large prehistoric reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs in the same geological layers as oil deposits on Svalbard. Could a minuscule amount of oil have come from these creatures? Maybe. But we’re talking about a drop in an ocean of algae-derived petroleum.

Could You Become Oil? (Asking for a Friend)

Here’s where things get interesting. If algae and plankton can transform into oil, what about humans? Could we, theoretically, become fuel for future civilizations?

Müller considered the question. “If we humans had piled up in a big clump on the ocean floor and stayed there for a long time, we could have become oil,” he explained. “We would also have to be covered by a thick layer of sand and lie there for a very long time.”

Before you start making weird jokes about your retirement plan, there’s a catch. Remember those hungry ocean scavengers? They’re not picky eaters. Human bodies would face the same fate as dinosaurs. Something would eat us long before we could be marinated in the Earth’s crust for millions of years.

Those ancient algae and plankton succeeded where dinosaurs and humans would fail for one simple reason. When they died and sank to the bottom of the seas, covering what would eventually become Norway and other oil-rich regions, there wasn’t much oxygen in the water. Without oxygen, there wasn’t much life on the seabed. Nothing ate them. They just accumulated, layer after undisturbed layer, waiting for pressure and time to work their magic.

But Wait, Aren’t We Making More Oil Right Now?

You might be thinking: if plankton and algae are still dying and sinking to the ocean floor today, doesn’t that mean we’re constantly making new oil? Won’t we eventually have more?

Technically, yes. Somewhere in the ocean right now, the earliest stages of oil formation are probably happening. Dead plankton is settling on the seabed. Sediment is covering it. In about 50 to 100 million years, that organic matter might become oil.

See the problem?

When experts talk about running out of oil, they’re not suggesting the Earth will completely run dry. Müller explained the real issue. “When we talk about running out of oil, the problem is that we are extracting the oil faster than new oil is made,” he said. “After a while, the oil field becomes too empty for it to be profitable to extract what’s left.”

We’re withdrawing from an account that takes geological ages to refill. We’re eating the seed corn. We’re spending our inheritance faster than Grandma Earth can earn interest. Pick your metaphor, but the math remains the same. Humans have used oil for decades, which took millions of years to create.

Where Did This Dinosaur Nonsense Come From Anyway?

If oil doesn’t come from dinosaurs, why does everyone think it does? Blame good marketing and a really effective mascot.

In 1933, Sinclair Oil Corporation sponsored a dinosaur exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair. Their reasoning? Oil reserves formed during the Mesozoic era, when dinosaurs lived. Same time period, so same source, right? Wrong, but it made for great branding.

Americans loved the exhibit. Sinclair leaned into the association, eventually adopting a large green brontosaurus as its official mascot. For decades, that friendly dinosaur appeared on gas stations across America, cementing in the public imagination that there was somehow a connection between prehistoric reptiles and petroleum.

Marketing worked a little too well. What started as a corporate symbol became an accepted fact. People forgot that correlation doesn’t equal causation. Just because dinosaurs and oil deposits both date to similar geological periods doesn’t mean one became the other.

Müller thinks we need to do better. He argues that people should understand where oil actually comes from, the same way they know basic facts about their own history and culture. “Oil has been important to us, so we should know where it comes from,” he said. “It sounds cool to say that oil is a kind of dinosaur soup, but this is pure fantasy.”

Why Does Any of This Matter?

You might wonder why a geologist cares so much about correcting this particular misconception. After all, whether your car runs on algae or dinosaurs, it still gets you to work, right?

But scientific literacy matters. Understanding where our resources actually come from helps us make better decisions about how we use them. When you know that oil represents millions of years of accumulated organic matter, processed under extreme conditions, never to be replaced on any timescale relevant to human civilization, you might think differently about burning through it.

When you understand that we’re not just pumping up dinosaurs but consuming a finite resource created over geological timescales from trillions of microscopic organisms, the climate emergency takes on new weight. We’re not just burning fuel. We’re burning ancient sunlight, captured by tiny organisms, stored in the Earth’s crust for eons, and now being released back into the atmosphere in the blink of a geological eye.

So next time you’re at the gas station, filling up your car, forget about the velociraptors. Think instead about the vast, unimaginable timescales involved. Think about countless microscopic organisms living, dying, and sinking through ancient seas. Think about the slow crush of geological pressure and the patient work of time and chemistry.

Your car isn’t running on liquefied dinosaurs. It’s running on processed plankton. Which, honestly, is just as amazing when you think about it.