Your cart is currently empty!

Why Octopuses Are Throwing Shells at Targets They Seem to Dislike

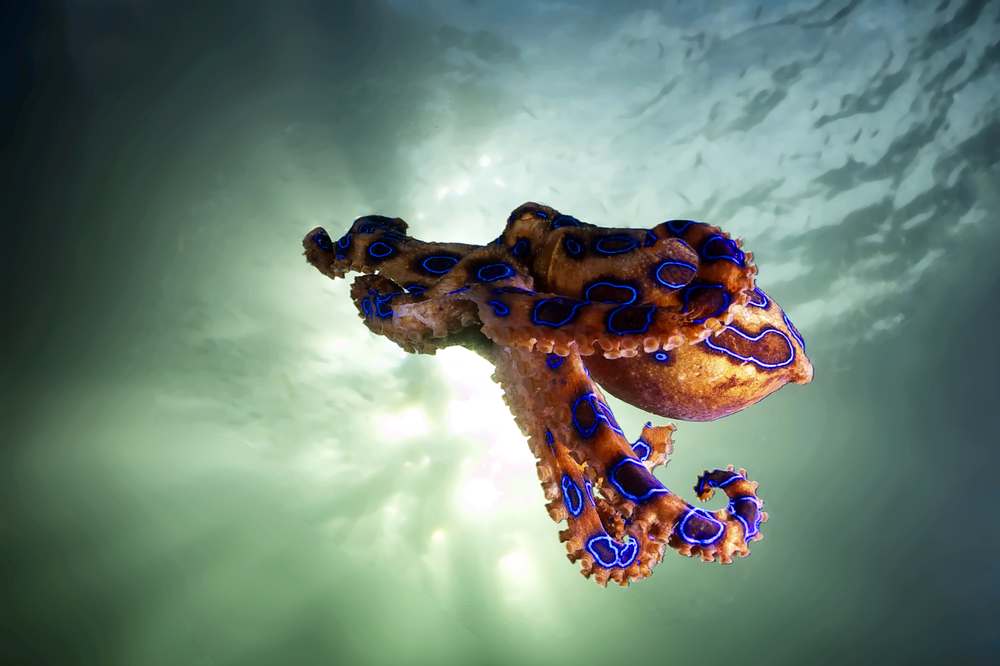

Octopuses have long been seen as mysterious and astonishingly intelligent animals, but new research from the waters of Australia and New Zealand has revealed something far more unexpected. Scientists studying the gloomy octopus observed a behavior that is so unusual in the animal world that it challenges long-held assumptions about how creatures without bones, tools, or humanlike arms might interact. Underwater cameras captured these octopuses gathering shells, silt, and algae before intentionally projecting them through the water at one another. The sight of an octopus launching debris at a neighbor feels almost humorous at first, but the more closely researchers examine the footage, the clearer it becomes that something meaningful is taking place beyond the novelty of the moment.

What makes this discovery so striking is not just that the octopuses throw things, but that the throws appear deliberate, controlled, and socially driven. Scientists noted that the animals often moved their siphons into an unusual position beneath the arm web in order to jet the debris forward, an action that requires effort and goal-directed behavior. These throws occurred in a variety of contexts, sometimes during den cleaning and sometimes in the middle of social interactions. Several throws even hit nearby octopuses, and according to the researchers, “there is some evidence that some of these throws that hit others are targeted, and play a social role.” These findings open a new window into octopus behavior, suggesting far richer emotional and social exchanges than previously documented.

The Rare Act of Throwing in the Animal Kingdom

Throwing is not a common behavior among animals, and scientists have long considered precise, targeted throwing to be especially exceptional. In their published study, Professor Peter Godfrey-Smith and his colleagues wrote, “The throwing of objects is an uncommon behavior in animals.” They further explained that “a throw can be distinguished from other phenomena by the ballistic motion of a manipulable object or material, where ‘ballistic’ describes free motion with momentum.” This definition helps separate true throwing from accidental displacement of material, highlighting the significance of what the octopuses were observed doing.

The research team noted that “throwing with aiming has sometimes been seen as distinctively human, and it probably does have an important role in hominin evolution.” Despite this, a handful of other species have shown the ability to throw with purpose. “Throwing at a target has also been observed in some non-human primates (especially chimps and capuchins), elephants, mongooses, and birds.” Related but less precise behaviors occur in other species as well, including spiders that flick hairs at threats and archerfish that squirt water through the air. The gloomy octopus now joins this small group of animals capable of coordinated projection of objects, and this addition is particularly astonishing because their anatomy makes such actions inherently challenging.

Across 24 hours of underwater footage, researchers observed 102 separate throwing events among roughly ten octopuses. This consistency suggests that throwing is not a rare accident but a natural and somewhat frequent component of their behavioral repertoire. It also hints at a social complexity that may run far deeper than previously recognized.

How Octopuses Manage the Mechanics of a Throw

Octopuses must overcome significant physical limitations when throwing objects. Unlike animals with arms or rigid limbs, octopuses rely entirely on soft tissue and water pressure. They gather shells or silt beneath them using their flexible arms and then reposition their siphon, which is usually used for movement. The deliberate placement of the siphon beneath the arm web appears crucial to performing a throw, and the researchers emphasized that this posture is unusual for typical octopus activity.

Once positioned, the octopus expels a forceful jet of water from the siphon to propel the collected debris forward. Some throws traveled several body lengths and reached other octopuses nearby. Scientists recorded that about 17 percent of these throws made contact with another individual, which is remarkable given the underwater medium and the difficulty of generating directional force without skeletal support.

This behavior may even qualify as a form of tool use. The octopus manipulates the material and also uses the water jet as a means of propulsion. Their ability to coordinate arm placement, siphon aim, and water force requires a blend of physical agility and cognitive planning. All of these factors offer a powerful reminder of the species’ adaptability and problem-solving abilities.

Key Components of Octopus Throwing

- Material gathering: shells, silt, algae, or debris brought beneath the body.

- Siphon manipulation: repositioning the siphon into an unusual angle.

- Force production: expelling water with enough pressure to launch material.

- Spatial judgment: directing the throw with apparent intent.

These steps highlight the complexity of the act and help explain why only a few animals are known to throw objects deliberately.

Why Gloomy Octopuses Throw Debris at Each Other

Understanding why octopuses throw materials is more complex than simply labeling the behavior as aggression. The footage shows several potential motivations that help paint a nuanced picture of octopus social life.

Many scientists believe crowded living conditions may contribute to these interactions. Jervis Bay hosts a dense population of gloomy octopuses because it offers an ideal combination of food sources and shelter opportunities. Solitary by nature, octopuses may find themselves irritated when forced into proximity with others of their kind. A projected cloud of silt or a shell launched across the sand might be a simple expression of annoyance or discomfort.

Another strong possibility is defense. Researchers found that 66 percent of the throws were made by females, many of whom were guarding possible egg sites. A well-timed throw could serve as a warning to an approaching animal, discouraging intrusion without the need for physical contact. In some cases, females even threw materials at males attempting to mate, suggesting a clear and deliberate method of signaling disinterest.

Some throws also occurred between individuals whose dens were located too close to each other. One female repeatedly launched silt at a neighboring octopus, whose response: ducking and raising its arms: suggested that it fully understood the action as intentional. This sequence reinforces the idea that throwing may be part of a broader communication system among octopuses, complementing their ability to change body color. Indeed, the study noted that darker coloration is commonly associated with aggression, and these darker individuals tended to throw more forcefully and with greater likelihood of hitting another octopus.

What These Throws Reveal About Octopus Intelligence

Octopuses already rank among the most intelligent invertebrates on Earth, and this behavior adds more evidence to that reputation. The researchers observed that “wild octopuses project various kinds of material through the water in jet-propelled ‘throws,’ and these throws sometimes hit other octopuses.” The fact that some throws occurred right after interactions and that individuals altered their behavior in response indicates that both the throwers and the recipients understood the social meaning behind the act.

Their nervous system, which includes a central brain and smaller neural clusters in each arm, supports an impressive level of distributed processing. This structure allows for multitasking and intricate movement control. When an octopus gathers debris, repositions its siphon, and times its water jet to achieve a directed throw, it demonstrates an advanced coordination of sensory input, memory, and physical action.

Furthermore, the octopuses’ ability to vary the type of throw depending on context suggests awareness. Some throws appeared casual or part of routine den cleaning, while others were clearly linked to interactions with other octopuses. The behaviors observed echo the remark from the researchers that “it is difficult to determine the intent of octopuses propelling debris through the water,” yet the consistent patterns make it hard to ignore the possibility of intentional targeting.

Environmental Pressures and Behavioral Adaptation Beneath the Waves

Although the throwing behavior itself is fascinating, it also opens larger discussions about how marine animals respond to environmental change. Dense aggregations like the one in Jervis Bay may reflect shifts in food availability, habitat structure, or the impacts of warming waters. As climate change continues to alter marine ecosystems, behaviors such as territoriality, communication, and conflict may become increasingly important to the survival of a species.

The gloomy octopus demonstrates an impressive ability to adapt both physically and behaviorally. As competition for resources intensifies, animals may develop new ways to negotiate space or defend their young. Understanding these dynamics provides researchers with valuable insight into how species adjust as oceans transform. Behavioral observations like targeted throwing could offer early clues about changing ecological pressures.

Marine scientists are also examining how octopus intelligence itself may play a role in resilience. The flexibility of their problem-solving skills, tool use, and social signaling may give them an advantage in unpredictable environments. Visual documentation of their behaviors allows researchers to track shifting patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

A Reflection on What Octopuses Can Teach Us

The discovery that octopuses hold grudges and throw shells at targets they do not like offers more than entertainment. It encourages us to rethink assumptions about underwater life and acknowledge the depth of emotion and decision-making occurring in species radically different from our own. These findings remind us that intelligence takes many forms and that the animals living in fragile marine ecosystems possess abilities we are only beginning to understand.

This behavior also carries a quiet warning. As climate pressures intensify, the survival of intelligent species like the gloomy octopus depends on how well we protect their environments. The more we learn about their inner lives, the stronger the argument becomes for safeguarding the oceans they depend on. Their throws, whether motivated by frustration, defense, or communication, are small but meaningful windows into how life adapts, responds, and expresses itself beneath the surface.