Your cart is currently empty!

Experts Issue Warning as Infected ‘Zombie’ Squirrels Covered in Warts Spotted in the Us

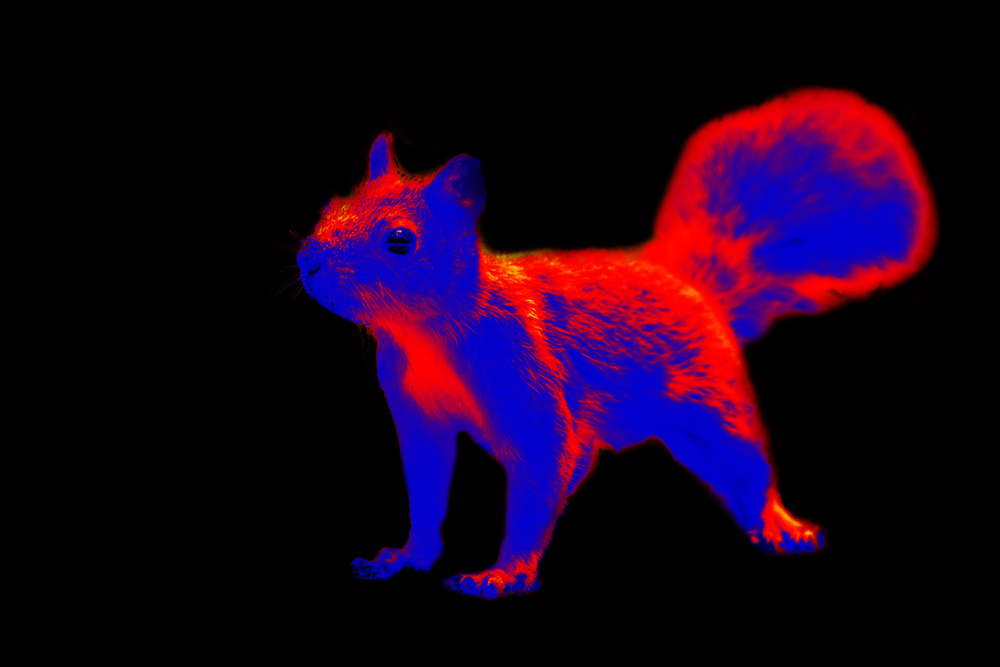

They dart across our backyards, scamper up trees, and raid bird feeders with enviable agility the squirrel has long been one of the most familiar, even endearing, sights in American suburbia. But lately, that image has taken on an unsettling twist. Across social media, photos of squirrels with grotesque, wart-like growths and patchy fur have left observers wondering: are these beloved backyard regulars turning into something out of a horror film?

The viral images have sparked headlines dubbing them “zombie squirrels,” drawing comparisons to The Last of Us and echoing recent reports of so-called “Frankenstein rabbits.” While the nickname may be sensational, the reality behind the phenomenon is less apocalyptic though no less fascinating. What’s happening to these animals, and why are so many people seeing them now?

The Strange Sightings Capture Public Attention

The first wave of alarm didn’t come from scientists, but from ordinary people scrolling their feeds. On Reddit, one user posted an image of a gray squirrel with what they initially mistook for food stuck to its face, only to realize the mass was part of the animal’s skin. Similar images soon surfaced on X, showing squirrels covered in tumors, bare patches of skin, and oozing sores. The descriptions ranging from “zombie squirrels” to comparisons with “creatures from a horror game” reflected the shock of seeing such a familiar animal transformed so grotesquely.

These sightings were not isolated. Reports date back at least to the summer of 2023, when residents in Maine photographed squirrels with scaly growths and sores, prompting local outlets like the Bangor Daily News to cover the issue. By mid-2025, however, the trend had grown harder to ignore, with online chatter giving the phenomenon a viral life of its own. Some joked darkly about a “rodent apocalypse,” while others, more disturbed than amused, pleaded for expert explanations.

The fascination is perhaps unsurprising. In recent years, unusual wildlife afflictions have repeatedly made headlines from rabbits with papillomavirus-induced growths earning the nickname “Frankenstein rabbits” to alarming global stories about “zombie viruses” thawing from permafrost. Against this backdrop, squirrels creatures so often associated with suburban normalcy and playfulness seemed to embody a jarring contrast: a touch of the macabre intruding on the everyday.

The Science Behind the Growths

Beneath the unsettling appearance of “zombie squirrels” lies a medical explanation rooted in virology. Wildlife experts identify two main culprits: squirrel fibromatosis and squirrel pox. Both are naturally occurring conditions that have circulated among squirrel populations for years, though the recent surge of online images has amplified public awareness.

Fibromatosis, caused by a leporipoxvirus, is particularly common in gray squirrels across North America. It leads to the development of wart-like tumors that can appear anywhere on the body from the face and legs to more sensitive areas like the eyes or genitals. These growths may ooze fluid, scab over, and in severe cases spread to internal organs. While most squirrels recover within weeks, such complications can occasionally be fatal. According to biologists, the disease is not cyclical like seasonal flu but spreads sporadically when conditions favor close contact among animals.

Squirrel pox, by contrast, is a more systemic and often deadlier condition most frequently associated with red squirrels in the United Kingdom, where it has contributed to steep population declines. In the United States, however, pox cases are less common and generally less devastating to local gray squirrel populations. That distinction has led many experts, including wildlife rehabilitators in Maine and Virginia, to suspect that most of the recent American cases are fibromatosis rather than pox.

Adding another layer of complexity, wildlife rescue centers point out that not all lumps are viral in origin. In some cases, squirrels suffer from botfly infestations, where larvae tunnel into the skin and cause swollen, boil-like protrusions. Unlike viral diseases, botfly infections require careful removal by trained professionals, not by well-meaning passersby.

The scientific consensus is clear: while these conditions look frightening, they are not new, nor are they a threat to humans. As wildlife biologist Shevenell Webb reassures, “It is naturally occurring and will run its course in time.” For the animals themselves, the experience can be debilitating but is often survivable, highlighting the resilience of these creatures even in the face of grotesque afflictions.

How the Diseases Spread Among Squirrels

For all their alarming appearance, the spread of these squirrel diseases follows patterns familiar in both human and animal communities: close contact and shared resources create fertile ground for transmission. In the case of fibromatosis and squirrel pox, saliva and lesions are the primary vehicles. When an infected squirrel eats from a common food source, its saliva can contaminate seeds or surfaces. The next squirrel to arrive unknowingly ingests the virus, perpetuating the cycle.

Bird feeders, a staple of many American backyards, have emerged as a significant driver of this problem. Wildlife biologist Shevenell Webb likens the feeders to crowded gathering places for humans: “It’s like when you get a large concentration of people. If someone is sick and it’s something that spreads easily, others are going to catch it.” The same principle applies to squirrels clustering around a seed-filled tray, where even a trace of saliva or an open sore can act as a viral conduit.

Seasonal behaviors also play a role. Sightings of diseased squirrels tend to peak in warmer months, when squirrels are most active in gathering food and when bird feeders are often replenished more regularly. These feeding stations, though intended for birds, inadvertently create cross-species meeting points that draw in opportunistic rodents. The more frequently squirrels come into contact with one another, the higher the likelihood that viruses spread from animal to animal.

The good news is that not every squirrel exposed to the virus will succumb to severe illness. Many recover on their own within four to eight weeks, and once cleared, they typically do not experience reinfection. Still, the growing number of public reports suggests that human interventions especially the widespread use of feeders may be unintentionally increasing the reach of these naturally circulating diseases.

Should Humans Be Concerned?

Despite the unsettling imagery of squirrels with tumors and open sores, experts stress that these conditions pose no direct risk to humans. The viruses behind squirrel fibromatosis and squirrel pox are species-specific, meaning they cannot jump from squirrels to people, pets, or birds. Even so, wildlife biologists consistently caution against interfering with or attempting to help infected animals.

“The instinct to rescue is understandable, but in this case, it can do more harm than good,” notes Shevenell Webb of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Not only is there little that the public can do medically for the animal, but handling a distressed squirrel can cause unnecessary stress to the creature and potential injury to the person. If a squirrel appears ill or visibly afflicted, the safest and most humane action is simply to keep one’s distance and allow nature to take its course.

For the animals themselves, the prognosis is mixed but generally hopeful. Most gray squirrels infected with fibromatosis recover naturally within several weeks, their immune systems clearing the virus without the need for intervention. In rare, severe cases where tumors spread to internal organs, the disease may prove fatal, but such outcomes are the exception rather than the rule. Squirrel pox, while more dangerous in red squirrels, remains relatively uncommon in North America.

Ultimately, the greatest risk lies not in human health but in the misperception of danger. Social media’s shorthand label of “zombie squirrels” amplifies fear, but the reality is far less sinister: these are not signs of a spreading plague, but examples of wildlife diseases that have long existed, occasionally surfacing in ways that are visually dramatic. For the public, the message is clear watch, report if necessary to local wildlife authorities, but resist the urge to intervene.

The Cultural Fascination with “Zombie” Wildlife

Part of what makes the “zombie squirrel” story so captivating is not just the biology, but the imagery. The term itself evokes horror films, video games like The Last of Us, and broader cultural anxieties about contagion and transformation. When photographs of afflicted squirrels began circulating online, they were quickly framed in language more akin to entertainment headlines than ecological reports “zombie squirrels,” “Frankenstein rabbits,” even speculation about an “apocalypse in the backyard.”

These parallels are more than coincidence. In recent years, popular culture has leaned heavily into pandemic and mutation narratives, from prestige television dramas to speculative documentaries. Against this backdrop, real-life sightings of visibly diseased animals feel like eerie echoes of fiction. The internet, with its appetite for both shock and humor, amplifies these moments memes, hashtags, and incredulous comments giving the story a viral half-life beyond the science.

Yet the fascination also reveals something about our relationship with nature. Squirrels are among the most recognizable and approachable wild animals in American life. To see them disfigured disrupts the familiar, making the ordinary strange. This sense of unease fuels both curiosity and compassion a reminder that even creatures we think of as resilient neighborhood fixtures are vulnerable to forces outside their control.

A Reminder of Respect for the Wild

The viral chatter about “zombie squirrels” may be fueled by shock and morbid fascination, but the reality is more grounded: these are not signs of an outbreak threatening humans, but natural diseases that wildlife has long carried and, in most cases, survived. The growths and sores, however grotesque, often resolve without intervention, and the most effective role humans can play is to observe responsibly, avoid direct contact, and limit practices such as overcrowded bird feeders that accelerate transmission.

Ultimately, the story of these squirrels is less about fear and more about perspective. It reveals how quickly unusual images can capture our imagination, how easily cultural narratives of contagion shape our reactions, and how vital expert voices are in grounding public understanding. Nature, even when it appears at its most unsettling, deserves both respect and restraint. The squirrels will likely recover, but the episode offers a lasting reminder: not every disturbing headline signals catastrophe sometimes, it is simply a glimpse into the complex resilience of the natural world.