Your cart is currently empty!

Finland Is Teaching Children to Spot Fake News Before Primary School Even Begins

In a quiet preschool classroom in Finland, children barely old enough to tie their shoes are being introduced to something many adults around the world still struggle with: how to question information, recognize misleading claims, and understand that not everything they see or hear is true. While other countries are only now reacting to the flood of fake news, manipulated videos, and viral falsehoods online, Finland has been preparing its citizens for this reality for decades. Media literacy is not treated as a trendy add on or a reaction to current events. It is woven into everyday learning from the very beginning of a child’s education, starting as early as age three.

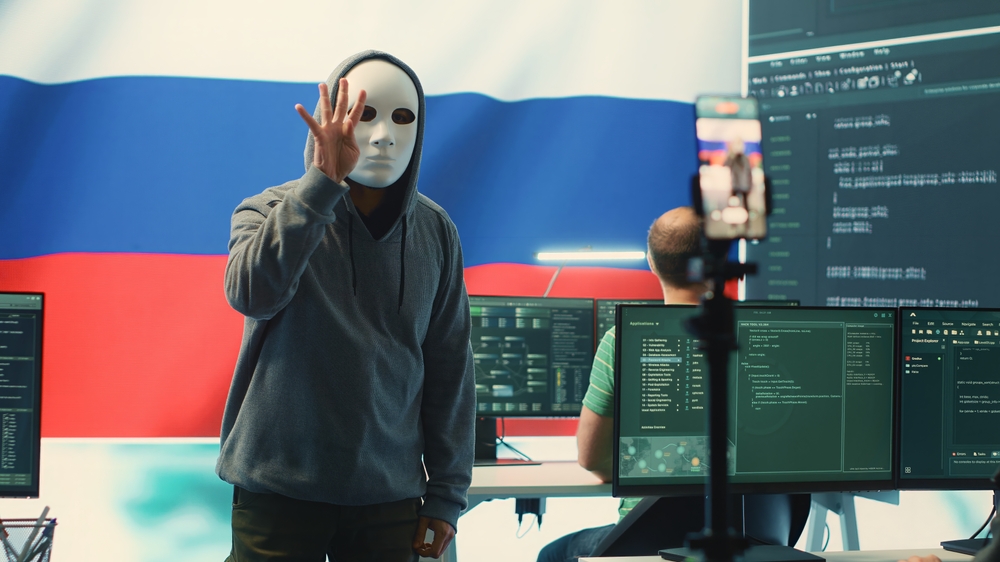

This long term approach has taken on new significance as geopolitical tensions rise across Europe and disinformation campaigns become more aggressive and more sophisticated. Finland shares a long border with Russia and has historically viewed information warfare as a real security concern rather than an abstract digital problem. As artificial intelligence accelerates the speed and realism of false content, Finland’s education system is increasingly seen as a quiet but powerful defense. Instead of banning platforms or chasing viral lies after the fact, the country has focused on teaching people how to think critically before misinformation has a chance to take hold.

Media literacy as a basic civic skill

For Finnish educators, media literacy is not framed as politics or ideology. It is treated as a foundational life skill, similar to reading comprehension or numeracy, and something that children gradually build as they grow. From preschool onward, students are encouraged to talk about where information comes from, why it was created, and how it makes them feel. These conversations are intentionally simple at first and become more complex over time.

Rather than relying on abstract theory, teachers integrate media literacy into everyday classroom activities. Children might compare advertisements, discuss headlines, or talk about the difference between opinion and fact. The emphasis is on curiosity rather than suspicion, helping students understand that questioning information is healthy and necessary in a modern democracy.

Kiia Hakkala, a pedagogical specialist for the City of Helsinki, explained the broader purpose behind this approach. “We think that having good media literacy skills is a very big civic skill,” she said. “It’s very important to the nation’s safety and to the safety of our democracy.” Her comments reflect a widely shared belief in Finland that informed citizens are essential to long term stability.

Why disinformation is treated as a security threat

Finland’s focus on media literacy cannot be separated from its geography or its history. The country shares a 1,340 kilometer border with Russia, and Finnish officials have long viewed influence campaigns and false narratives as tools that can weaken trust in institutions and divide societies from within. In recent years, those concerns have intensified.

After Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine, European countries reported a noticeable increase in coordinated disinformation efforts. Finland’s decision to join NATO in 2023 further heightened tensions, even as Russian officials denied interfering in the internal affairs of other nations. Finnish policymakers, however, have chosen not to dismiss the threat.

Instead of responding with panic or censorship, Finland has doubled down on prevention. By ensuring that citizens are able to identify manipulation for themselves, officials believe the country becomes more resilient. The goal is not to control information, but to reduce its power to deceive.

Learning to spot fake news in primary school

At Tapanila Primary School in a residential area north of Helsinki, media literacy lessons are already second nature to students. In one classroom, fourth graders are presented with headlines and images and asked to decide whether they represent fact or fiction. The exercise is deliberately challenging, mirroring the complexity of real world online content.

Ten year old student Ilo Lindgren admitted the process is not always straightforward. “It is a little bit hard,” she said, acknowledging that false information is often designed to look convincing. Teachers see this difficulty as part of the learning process rather than a failure.

Ville Vanhanen, a teacher and vice principal at the school, explained that students have been developing these skills for years. They start with short texts and simple examples before gradually moving on to more complex digital material. The aim is not to tell students what to believe, but to help them build habits of careful evaluation.

Artificial intelligence raises the stakes

As artificial intelligence tools become more advanced and more accessible, Finnish educators are once again adapting their curriculum. Students are now learning how to recognize images, videos, and audio that may have been generated or altered by AI. This includes examining visual inconsistencies, unnatural patterns, and contextual clues that something may not be authentic.

Vanhanen said his students are already studying how to identify AI generated content. “We’ve been studying how to recognize if a picture or a video is made by AI,” he said. The lessons reflect a growing awareness that traditional media literacy alone is no longer enough.

Experts warn that this window of detectability may not last. Martha Turnbull, director of hybrid influence at the Helsinki based European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, cautioned that future developments could make false content far harder to spot. “It already is much harder in the information space to spot what’s real and what’s not real,” she said. “But as that technology develops, I think that’s when it could become much more difficult for us to spot.”

The role of trusted journalism

Finland’s effort to build resilience against misinformation extends beyond the classroom. Media organizations actively collaborate with schools to help young people develop a relationship with reliable journalism before social media becomes their primary source of news. One major initiative is the annual Newspaper Week, during which newspapers and digital news are distributed to students across the country.

In 2024, the daily newspaper Helsingin Sanomat partnered on an “ABC Book of Media Literacy,” which was given to every 15 year old as they entered upper secondary school. The project was designed to reinforce the idea that credible information comes from transparent processes and accountable institutions.

Managing editor Jussi Pullinen emphasized the importance of trust. “It’s really important for us to be seen as a place where you can get information that’s been verified,” he said. “That you can trust, and that’s done by people you know in a transparent way.”

A society shaped by critical thinking

Media literacy has been part of Finland’s national curriculum since the 1990s, and its influence extends well into adulthood. Additional courses are available for older citizens, who studies suggest may be especially vulnerable to online misinformation. This lifelong approach has helped embed critical thinking into Finnish culture.

As a result, Finland consistently ranks at the top of the European Media Literacy Index, compiled by the Open Society Institute in Sofia between 2017 and 2023. While no system is perfect, the results suggest that long term investment in education can have measurable impacts.

Education Minister Anders Adlercreutz acknowledged that the scale of today’s challenges was difficult to predict. “I don’t think we envisioned that the world would look like this,” he said. “That we would be bombarded with disinformation, that our institutions are challenged, our democracy really challenged, through disinformation.”

What other countries can take away

Finland’s approach stands in contrast to countries that rely primarily on reactive fact checking or platform moderation. Instead of chasing false claims after they spread, the Finnish model focuses on preparation and resilience. It assumes misinformation will always exist and prioritizes the skills needed to confront it.

Key elements of this approach include starting education early, integrating critical thinking across subjects, and treating media literacy as a civic responsibility rather than a political statement. Just as importantly, Finland is already preparing students for future technologies rather than only addressing current threats.

By trusting education over fear and long term thinking over quick fixes, Finland has created a population better equipped to question, verify, and reflect. In an era when false information spreads faster than ever, the country offers a reminder that the strongest defense against propaganda is not censorship, but literacy.