Your cart is currently empty!

Artificial Intelligence Is Designing Viruses and Raising New Questions About Biosecurity

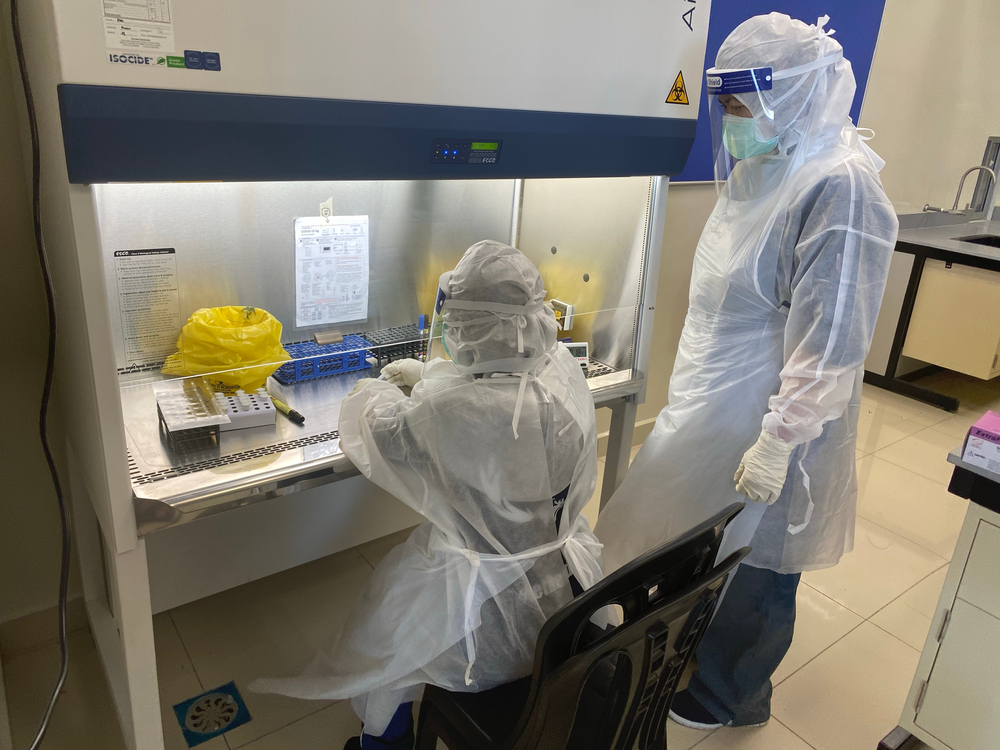

For decades, the most powerful tools in biology were physical ones microscopes, petri dishes, and high security laboratories. Now, some of the earliest decisions in biological research are being made on computer screens. Scientists are using artificial intelligence to explore genetic possibilities before a single molecule is built, and that shift is quietly changing how life science research starts, long before it reaches a lab bench.

This change has unsettled many people, in part because it challenges assumptions about where biological risk begins. AI systems trained on genetic data can propose designs that researchers once had to discover slowly, through years of trial and error. That capability has sparked concern, not because machines are running unchecked experiments, but because it forces a closer look at whether existing safety systems are prepared for a world where biological ideas can move faster than the rules designed to monitor them.

When “Creating a Virus” Really Means Writing Code First

When researchers talk about AI creating viruses, they are describing a shift in where biological work begins rather than a machine producing living organisms. In this context, artificial intelligence is used to analyze large collections of existing viral genomes and learn the patterns that tend to appear in nature. From those patterns, the system can propose complete genetic sequences that look internally consistent and biologically plausible, much like a skilled researcher sketching out a theoretical design based on years of experience.

What the AI produces at this stage is not a virus in the physical sense but a digital blueprint. These sequences exist as data and only become meaningful if scientists choose to test them in a laboratory. Even then, most proposed designs never work as intended. Turning a sequence into something that can replicate requires careful validation, specialized equipment, and extensive experimentation, and failure is common. The AI does not bypass those steps or guarantee success.

What has changed is the pace and breadth of exploration. Instead of examining a handful of ideas at a time, researchers can now review many possible genome designs quickly, including ones that do not closely resemble any single known virus. That expanded search space is valuable for discovery, but it also makes outcomes harder to predict using familiar reference points, which is why scientists are paying close attention to how this new starting point in biology fits within existing safety and oversight systems.

Why Researchers Turned to Viruses That Only Target Bacteria

To understand whether AI generated genetic designs can function at all, scientists needed a system that was both informative and tightly controlled. Bacteriophages fit that role because they have been studied for decades and behave in predictable ways under laboratory conditions. Researchers already know how these viruses infect bacteria, how quickly they replicate, and how to measure success when a new design works. That depth of existing knowledge makes it easier to tell whether a failure comes from a flawed genetic design or from experimental noise.

Phages also allow researchers to move carefully but efficiently. Because they infect specific bacterial strains that can be grown and controlled in the lab, scientists can isolate the performance of a proposed genome without the added complexity of immune responses or unpredictable host factors. This matters when testing AI generated sequences, where the central question is whether a design makes biological sense in the first place. By using bacteriophages, researchers could focus on whether patterns learned from known viruses were enough to produce new, functional ones, while keeping safety and logistics firmly within manageable bounds.

How a Safety System Was Quietly Put to the Test

Rather than speculating about worst case scenarios, the researchers behind the Science study chose to examine something far more concrete. They asked how today’s safety systems actually perform when confronted with the kinds of biological designs that modern AI tools can already produce. Their focus was the screening process used by DNA synthesis companies, which acts as a checkpoint before genetic material is ever manufactured. These systems are designed to flag sequences associated with known pathogens or toxins, helping prevent misuse long before anything reaches a laboratory.

To test those safeguards, the researchers used AI driven protein design tools to modify proteins that are already recognized as hazardous. The goal was not to create something new, but to see whether these tools could alter existing sequences in ways that preserved their likely function while changing their genetic appearance. In many cases, the redesigned sequences no longer resembled known threats closely enough to trigger standard screening alerts. This result pointed to a deeper issue, not negligence, but a mismatch between how risk has traditionally been defined and how AI can now generate biological novelty.

The study also showed that this gap is not permanent. By shifting screening methods away from simple sequence matching and toward assessments based on protein structure and function, the researchers were able to detect many of the redesigned sequences that previously slipped through. In doing so, the study demonstrated both the challenge and the opportunity presented by AI in biology. As design tools evolve, safety systems must evolve alongside them, and when vulnerabilities are examined openly, they can be addressed before they become real world problems.

Why the Leap From Code to Catastrophe Is Still a Long One

The idea that a computer generated genetic sequence could quickly turn into a dangerous biological weapon misunderstands how much work still stands between a digital design and a living organism. Writing a genome is only the starting point. Transforming that information into a virus capable of infecting humans requires specialized facilities, trained experts, repeated rounds of testing, and careful control at every stage. Even in tightly managed research settings, most proposed designs never behave as intended, and the recent experiments focused on simple bacterial viruses rather than the far more complex pathogens that cause human disease.

At the same time, scientists are realistic about why this area deserves attention. Advances in automation, falling costs for DNA synthesis, and increasingly capable AI tools do make early exploration faster than it once was. That does not erase the need for expertise or infrastructure, but it does shift where safeguards need to be strongest. Instead of trying to predict intent, biosecurity efforts concentrate on points in the process where oversight can still be applied consistently and effectively.

One of the most important of those points is DNA synthesis itself. Companies that produce genetic material increasingly screen both the sequences being ordered and the identities of customers placing those orders. Newer screening methods are designed to look beyond simple genetic matches and assess whether a sequence is likely to function in harmful ways. Shared industry standards and funding policies that favor vetted suppliers add further layers of accountability. Taken together, these measures mean that while AI is changing how biological research begins, it has not removed the practical and institutional controls that make the rapid or casual creation of bioweapons unlikely.

When Scientific Progress Brings New Questions About Responsibility

Most advances in science arrive with mixed consequences, and AI driven biology is no exception. The core concern is not that researchers are setting out to do harm, but that the tools they are using change how easily certain kinds of biological ideas can be explored. Work that begins with legitimate goals, such as understanding disease or designing new treatments, can also reveal pathways that were previously difficult to access, simply because the technology reduces time, effort, and technical barriers at the earliest stages of research.

AI systems trained on biological data are especially influential at this exploratory phase. They can suggest many possible protein or genome designs quickly, reducing the need for slow, manual trial and error. Tasks that once demanded years of specialized experience can now be approached more efficiently, which expands who can participate in early biological design. As that pool grows, the challenge for oversight systems becomes less about spotting obvious red flags and more about keeping pace with the volume and novelty of what can be proposed digitally.

This shift is examined in an open access paper published in PNAS Nexus, where researchers describe it as a new category of dual use capability that complicates traditional risk assessment. Rather than focusing on malicious intent, the authors point to uncertainty as the central issue, especially when monitoring systems are built to recognize known threats. When AI generates designs that are unfamiliar but still biologically plausible, existing controls struggle to evaluate risk early on. The paper argues that established governance frameworks from earlier life science research remain relevant, but only if they are updated to account for scale, access, and capability instead of relying solely on lists of specific sequences.

A Turning Point That Demands Care, Not Panic

The rise of AI in biology is not a signal that danger is inevitable, but it is a clear marker that the rules of the field are changing. Research that once unfolded slowly and visibly is now beginning earlier, moving faster, and starting in digital spaces that existing safeguards were not originally designed to monitor. That shift exposes weaknesses, but it also offers a rare opportunity to strengthen oversight while the technology is still taking shape.

What matters now is how societies respond to that moment. Fear driven reactions risk obscuring both the limits of the technology and its real potential to improve human health. Careful attention, informed public discussion, and adaptive safety systems allow progress and protection to move forward together. The choices made at this stage will shape whether AI becomes a source of preventable risk or a tool that advances medicine while remaining firmly under responsible control.