Your cart is currently empty!

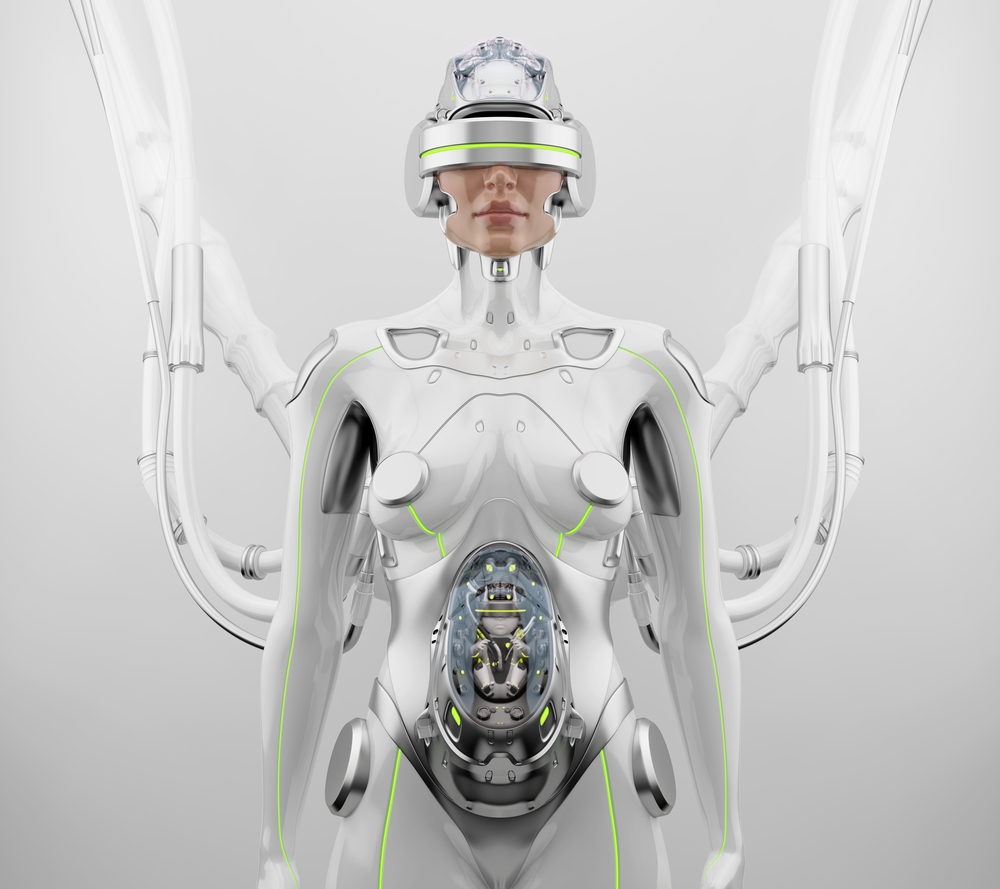

Scientists Develop World’s First ‘Pregnancy Robot’ That Can Give Birth to Living Babies

For centuries, the ability to carry and nurture new life has been seen as one of the most uniquely human experiences. Yet, in a striking turn of science and technology, researchers in China are attempting to hand that role to machines. Imagine a world where babies are not born from mothers’ wombs, but from humanoid robots equipped with artificial womb a future that once belonged in science fiction novels, now approaching reality.

At the 2025 World Robot Conference in Beijing, Chinese scientist Dr. Zhang Qifeng unveiled a plan to create the world’s first humanoid robot capable of carrying a pregnancy to term. Behind its polished exterior lies an artificial womb that mimics the intricate conditions of human gestation from synthetic amniotic fluid to nutrient delivery systems. If successful, the first prototype could be ready as soon as 2026, priced at around $13,900, far less than the cost of surrogacy in many countries.

The implications reach far beyond a scientific milestone. With global infertility affecting an estimated 15% of couples, such a robot could offer new hope to millions who struggle to conceive. At the same time, it has ignited fierce debate: is this the dawn of a new era in reproductive medicine, or the first step toward a dystopian future where motherhood is outsourced to machines?

The Science Behind the Pregnancy Robot

At the center of Kaiwa Technology’s groundbreaking project is a humanoid robot designed to do what, until now, only the human body could: carry a baby from conception to birth. Unlike a traditional incubator, which supports premature infants after partial gestation, this system is built to replicate every stage of pregnancy, offering a controlled environment for fetal development over the full ten-month cycle.

The key innovation lies in its artificial womb, engineered to simulate the complex functions of a human uterus. Inside the robot’s abdomen, a fetus would float in synthetic amniotic fluid, shielded and cushioned much like in a natural womb. Nutrients and oxygen would be delivered through a specialized tube functioning like an umbilical cord, while advanced sensors regulate temperature, monitor growth, and ensure proper development. This creates not just a mechanical cradle, but a biological ecosystem designed to mirror the delicate balance of human gestation.

Dr. Zhang Qifeng, the scientist behind the project, describes the technology as being in a “mature stage,” meaning the scientific principles have already been demonstrated in laboratory settings. The next step is integrating the artificial womb into a humanoid form not merely a container, but a life-sized robot capable of interacting with people while carrying a pregnancy.

This leap builds on years of research into artificial gestation. In 2017, scientists at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia made headlines when they kept premature lambs alive for several weeks in a “biobag” a transparent sac filled with warm, saline-based artificial amniotic fluid. The lambs continued to develop normally, even growing wool. That experiment was a landmark, showing that it was possible to nurture life outside a biological womb. The humanoid pregnancy robot takes that concept further, aiming not just to support partial gestation, but to reproduce the entire process from fertilization to delivery.

Why This Technology Matters

The idea of a robot carrying a pregnancy may sound like science fiction, but the motivations behind it are firmly grounded in urgent medical and social realities. Around the world, infertility affects an estimated 15% of couples, according to the World Health Organization. In China alone, the rate has climbed from 11.9% in 2007 to 18% in 2020, a trend that has sparked concern amid declining birth rates and shifting demographics. For many of these couples, access to treatment remains limited, costly, or fraught with legal hurdles.

The humanoid pregnancy robot could provide a new path forward. Unlike traditional surrogacy, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars and is banned or restricted in several countries, Kaiwa Technology’s prototype is expected to be priced at roughly 100,000 yuan (around $13,900). By comparison, commercial surrogacy in the United States can exceed $100,000 once medical, legal, and agency fees are included. The potential affordability could make artificial womb technology accessible to a far broader range of families.

Beyond financial barriers, the robot also addresses health risks associated with human pregnancy. Complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and postpartum hemorrhage remain major threats worldwide. In countries with limited maternal healthcare infrastructure, the risks are even higher. A robotic gestation system, by carrying the physical burden, could reduce these dangers while giving women who are unable or unwilling to undergo pregnancy a safe alternative.

The scientific community also sees promise in the robot as a research tool. By providing a controlled, observable environment, artificial wombs could allow doctors and geneticists to study complications of pregnancy, developmental disorders, or the impact of environmental factors on fetal health with unprecedented precision. For conditions that remain poorly understood from preterm birth to genetic syndromes this level of access could accelerate breakthroughs in treatment and prevention.

History provides a telling parallel. When in vitro fertilization (IVF) was first introduced in the late 1970s, it was met with skepticism, controversy, and even moral outrage. Today, more than 8 million babies worldwide have been born through IVF, and the technique is widely accepted as a legitimate solution to infertility. Supporters of artificial womb technology believe it could follow a similar trajectory: once controversial, eventually transformative.

Global Reactions and Comparisons

The announcement of a pregnancy-capable robot has captured global attention, sparking fascination, skepticism, and unease in equal measure. In China, where the project was unveiled, public opinion is deeply divided. For some, the development offers a beacon of hope amid rising infertility rates and demographic challenges. For others, it provokes anxiety about a future where machines replace some of the most intimate aspects of human life.

Internationally, the coverage has been just as polarized. Western media outlets have described the invention as both a “revolutionary breakthrough” and a “dystopian prospect.” Bioethics experts in Europe and the United States have acknowledged its potential to expand reproductive choices but warn that oversight and transparency will be crucial to prevent exploitation or misuse. The debate echoes earlier reactions to disruptive biotechnologies most notably the first “test-tube baby” in 1978. At that time, headlines warned of unnatural science tampering with life, yet today IVF is a mainstream treatment responsible for millions of births worldwide.

Observers have also drawn comparisons to other recent innovations blending artificial intelligence and biology. At the same 2025 World Robot Conference, researchers unveiled GEAIR, an AI-powered breeding robot that integrates gene editing and robotics to accelerate crop breeding. Like the pregnancy robot, it highlights China’s ambition to merge biotechnology and robotics to address pressing social needs whether feeding populations or tackling infertility.

Risks, Challenges, and Unknowns

Despite its futuristic promise, the pregnancy robot faces significant hurdles before it can be considered a safe or reliable alternative to natural gestation. Human pregnancy is a profoundly complex biological process, and many aspects remain difficult, if not impossible, to replicate with machines.

One major challenge lies in the role of maternal hormones. During pregnancy, hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and oxytocin regulate not just fetal growth but also immune tolerance, brain development, and the emotional connection between mother and child. While an artificial womb can provide nutrients and oxygen, it cannot yet replicate the intricate biochemical interplay that takes place in the human body. Critics argue that overlooking these subtleties risks unforeseen developmental or psychological consequences for children born from machines.

Another scientific gap involves the earliest stages of life fertilization and implantation. While Kaiwa Technology claims the artificial womb is ready to support full-term gestation, details on how embryos would be implanted and sustained from the very beginning remain vague. Current artificial womb research has only reliably supported life at later stages, such as premature lambs in biobag experiments. Achieving seamless fertilization-to-birth continuity is still unproven.

Social risks are equally pressing. The technology raises the possibility of commercial exploitation, from black markets in eggs and sperm to profit-driven surrogacy industries that treat childbirth as a commodity. Bioethicists also warn of psychological challenges: how might children conceived and grown in robots process the knowledge of their origins, and what does it mean for family identity and belonging?

History reminds us that revolutionary technologies often stumble before they succeed. From early failures in IVF to setbacks in cloning, scientific progress rarely moves in a straight line. For the pregnancy robot, both the technical and ethical road ahead remains uncertain and society must grapple with these unknowns long before the first baby is ever born from a machine.

The Future of Reproduction: Liberation or Loss?

The arrival of a pregnancy robot forces society to confront questions that extend far beyond science. At its core, the technology challenges deeply held ideas about what it means to create and nurture life. For some, it represents a form of liberation: freeing women from the physical risks and burdens of pregnancy, expanding reproductive possibilities for those unable to conceive, and offering families new hope where medicine has failed. Advocates argue that just as IVF transformed infertility treatment in the late 20th century, artificial wombs may one day normalize a safer, more inclusive vision of parenthood.

Yet others see potential loss in this shift. Pregnancy has long been understood not only as a biological process but also as an emotional and social one a shared journey that binds parents and children even before birth. Critics warn that outsourcing gestation to machines could weaken these bonds, turning the beginning of life into a mechanical process detached from human intimacy. Feminist thinkers caution that the technology could be co-opted to marginalize women’s roles in reproduction, reducing motherhood to a relic of the past.

The future may lie somewhere in between these extremes. If prototypes prove successful, widespread use is unlikely to emerge overnight. Instead, society could see gradual adoption perhaps first in medical research and infertility treatment, then in more personal contexts. By the 2030s or 2040s, artificial wombs may no longer be novelties but part of a wider landscape of reproductive choices, existing alongside natural pregnancy, IVF, and surrogacy.

What remains clear is that such advances will not only reshape family life but also prompt societies to revisit ethical, cultural, and legal definitions of parenthood. Science may be building the tools, but it is people, communities, and governments who will ultimately decide how or whether to embrace them.

Preparing for a New Era

The idea of a machine giving birth may once have sounded like pure science fiction, but with China’s pregnancy robot edging closer to reality, the boundary between human biology and technology is shifting in profound ways. For millions facing infertility, this invention could offer new hope; for researchers, it could open doors to insights into pregnancy never before possible. At the same time, it poses weighty questions about ethics, identity, and the meaning of parenthood.

Like every transformative technology before it, the pregnancy robot demands not only scientific rigor but also public dialogue and ethical oversight. The challenge is to ensure that innovation serves humanity rather than unsettling it that artificial wombs are used to support families and advance medicine, not commodify life or diminish human connection.

As the world watches the countdown to the first prototype in 2026, we are reminded that progress does not wait for consensus. The true test will not be whether machines can give life, but whether society is ready to accept and wisely govern such a possibility.