Your cart is currently empty!

Radio Waves Meant for Submarines Created an Invisible Shield in Space

Humanity has a habit of changing the planet in ways no one expects. We see it in rising sea levels and vanishing glaciers. We saw it when the DART mission knocked an asteroid off course, proving our species could move celestial bodies. Yet some of our most profound impacts happen without any intention at all, in places we cannot see and barely understand.

Something strange has been happening in the space around Earth. For decades, scientists assumed the bands of radiation surrounding our planet behaved according to natural forces alone. Solar winds, cosmic rays, and magnetic fields seemed to dictate everything about these invisible structures. But NASA researchers studying data from specialized probes found something that defied their expectations. An artificial barrier now exists at the edge of one of these radiation bands, and humans created it without ever meaning to.

How did we build a shield in space without knowing? And what does its existence mean for our future? Answering those questions requires a journey through Cold War nuclear tests, submarine communications, and the invisible forces that protect our planet from the harshness of space.

Our Planet’s Natural Defense System

Earth sits in a dangerous neighborhood. Cosmic rays from distant supernovae and powerful solar winds from our own Sun constantly stream toward us. Without protection, these high-energy particles would strip away our atmosphere and bombard the surface with radiation.

Fortunately, our planet generates a magnetic field that acts as a shield. Produced by churning molten iron in Earth’s core, the magnetic field extends thousands of kilometers into space. It deflects most incoming particles and channels others along invisible lines of force toward the poles. When these charged particles slam into atmospheric gases, they create the shimmering curtains of the Northern and Southern Lights.

But the magnetic field does more than deflect and channel particles. It also traps them. Swarms of electrons and ions become caught in the field’s grip, unable to escape but unable to reach the surface. These trapped particles form distinct structures in the space around Earth, and their discovery would reshape our understanding of the near-Earth environment.

Meet the Van Allen Belts

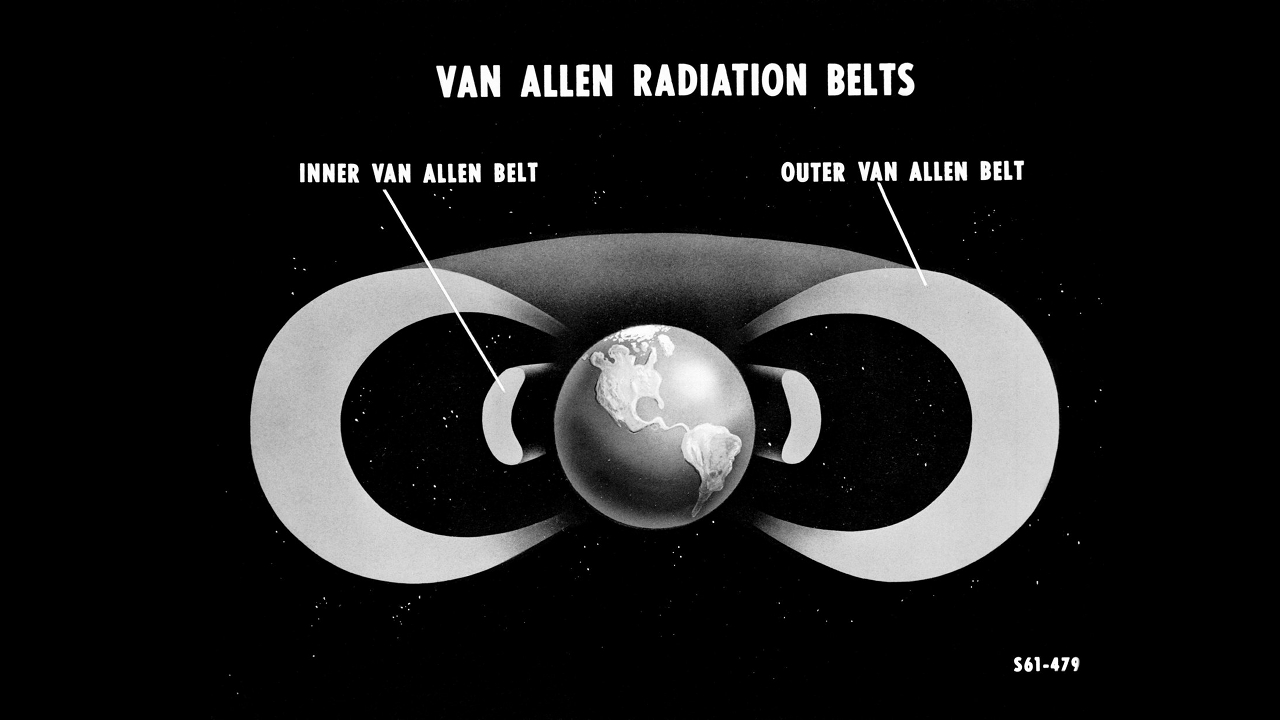

In 1958, physicist James Van Allen confirmed what his instruments aboard Explorer 1 had detected. Bands of intense radiation encircled the planet, held in place by Earth’s magnetic field. Scientists named these structures the Van Allen radiation belts in his honor.

Picture two concentric donuts wrapped around Earth. An inner belt sits between 1,000 and 6,000 kilometers above the surface. An outer belt, larger and more variable, stretches between 13,000 and 60,000 kilometers up. Both contain high-energy particles that pose serious risks to satellites and astronauts passing through them.

Shape and intensity of these belts shift in response to solar activity. When the Sun erupts with coronal mass ejections or solar flares, the belts can swell and intensify. During quiet periods, they settle into more stable configurations. For decades, scientists believed only these natural forces determined the belts’ behavior and boundaries.

NASA launched twin spacecraft in 2012 to study the Van Allen belts with unprecedented precision. Named the Van Allen Probes, these hardy machines orbited through the radiation bands until their mission ended in 2019. The data they collected would reveal surprises no one anticipated, including evidence that natural forces alone could not explain everything about the radiation environment around Earth.

Cold War Experiments Left Their Mark

Before examining what the Van Allen Probes found, we must reckon with an earlier chapter of human interference in space. Our species did not stumble into affecting the near-Earth environment by accident alone. During the Cold War, we actively and deliberately altered it through some of the most dangerous experiments ever conducted.

Between 1958 and 1962, both the United States and the Soviet Union detonated nuclear weapons at high altitudes. Operation Argus, Operation Hardtack, and the infamous Starfish Prime test sent atomic fireballs blooming in the upper atmosphere and beyond. Military planners wanted to understand how nuclear explosions would behave in space and whether they could destroy incoming missiles.

Results proved catastrophic in ways no one predicted. These explosions created artificial radiation belts that persisted for years. Satellites passing through the new bands of radiation suffered major damage. Starfish Prime alone disabled or destroyed at least six spacecraft. Another unexpected consequence emerged in the form of electromagnetic pulses that could affect electronics across areas as large as the continental United States.

International treaties eventually banned such tests, but they demonstrated a sobering truth. Humans possessed the power to reshape the space environment around Earth, whether we intended to or not. Decades later, scientists would discover we had been doing exactly that through far more mundane means.

An Unexpected Discovery from NASA’s Van Allen Probes

Van Allen Probe data revealed that radiation belts look radically different depending on particle energy levels. High-energy electrons occupy different regions than lower-energy particles. Simple donut models could not capture the true complexity of these structures.

Yet the most startling finding had nothing to do with natural particle behavior. Researchers noticed that the inner edge of the Van Allen belts sat farther from Earth than measurements from the 1960s suggested it should. Something appeared to be pushing the radiation outward, creating a distinct boundary that held firm against incoming particles.

Scientists traced the cause to an unlikely source. Not satellites, despite their presence in orbit. Not residual effects from long-ago nuclear tests. Instead, the culprit turned out to be radio waves generated on Earth’s surface and beamed into the deep ocean.

Submarines Talking to Space

Military submarines require a way to receive communications while submerged. Radio waves at most frequencies cannot penetrate seawater, but very low frequency waves, known as VLF, can reach submarines operating at significant depths. Nations with submarine fleets have operated powerful VLF transmitters for decades, sending signals at frequencies between 3 and 30 kilohertz.

Ground stations pump enormous amounts of power into these transmissions. Signals travel through water to reach submarines, but they also travel upward. VLF waves extend beyond our atmosphere, radiating outward and wrapping Earth in an invisible bubble of radio energy.

Spacecraft orbiting high above the surface can detect this bubble. “A number of experiments and observations have figured out that, under the right conditions, radio communications signals in the VLF frequency range can in fact affect the properties of the high-energy radiation environment around the Earth,” explained Phil Erickson, assistant director at the MIT Haystack Observatory and co-author of research that identified the phenomenon.

VLF waves interact with charged particles trapped in Earth’s magnetic field. When particles encounter these radio waves, their trajectories change. Energy transfers between waves and particles, altering where the particles travel and how far from Earth they can venture. Over decades of continuous VLF transmission, these interactions have reshaped the inner boundary of the Van Allen belts.

A Bubble That Pushes Radiation Away

Van Allen Probe data made the connection undeniable. The outward extent of the VLF bubble corresponds almost exactly to the inner edge of the Van Allen radiation belts. Where VLF transmissions reach, radiation gets pushed back. Where they fade, particles crowd closer to Earth.

Dan Baker, director of the University of Colorado’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, gave this boundary a memorable name. He called it the “impenetrable barrier” because particles from the outer belt cannot seem to cross it under normal conditions. Something holds them at bay.

Baker and other researchers speculate that without human VLF transmissions, this barrier would sit much closer to Earth’s surface. Evidence supports their hypothesis. Satellite measurements from the early 1960s, when VLF transmissions operated at lower power and with less frequency, showed the inner edge of the radiation belt sitting nearer to the planet. Modern measurements show it has retreated outward as VLF technology expanded.

Humanity built a shield in space without ever planning to do so. Submariners receiving orders beneath Arctic ice and military communications specialists monitoring transmitter stations had no idea their work was altering the radiation environment thousands of kilometers overhead. Yet the evidence suggests they have been doing exactly that for decades.

Could We Use It on Purpose?

Once scientists understood what VLF transmissions could do by accident, a natural question emerged. Could we harness this effect deliberately? If radio waves can push radiation away from Earth, perhaps we could use them to protect spacecraft, satellites, or even the planet itself during severe space weather events.

Solar storms pose genuine risks to modern technology. When the Sun hurls massive clouds of charged particles toward Earth, these particles can damage satellites, disrupt communications, and even threaten power grids on the surface. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station must sometimes shelter in protected areas during intense storms. Future crews traveling to the Moon or Mars will face even greater exposure.

Plans are already underway to test VLF transmissions in the upper atmosphere to see if they could remove excess charged particles that appear during periods of intense space weather. If successful, such transmissions might offer a way to clean up the near-Earth environment after solar storms, reducing risks to satellites and crews in orbit.

Other researchers have proposed using VLF to create safe corridors through radiation belts, allowing spacecraft to pass through with reduced exposure. While such applications remain speculative, the discovery that VLF affects radiation at all has opened possibilities no one imagined a few decades ago.

What Accidental Shields Teach Us

Our species has proven remarkably good at changing the planet without intending to. Fossil fuel combustion has released enough carbon dioxide to alter global climate patterns. Chemical refrigerants created a hole in the ozone layer before international cooperation phased them out. Nuclear tests created artificial radiation bands that damaged early satellites.

Now we can add another item to the list. Radio communications designed to reach submarines have created a barrier in space that pushes natural radiation away from Earth. Unlike climate change or ozone depletion, this particular accident may have beneficial effects. Yet it also reminds us that human technology extends far beyond the places we intend it to reach.

Earth’s magnetic field has protected life on this planet for billions of years. Van Allen belts trap dangerous radiation that might otherwise reach the surface. Into this ancient system, humanity has introduced a new element without planning, study, or forethought. VLF transmissions now help shape where radiation sits in the space around our world.

What other unintended consequences await discovery? What other shields or hazards have we created without knowing? These questions matter as human activity extends further into space. Satellites multiply in orbit. Plans advance for lunar bases and Mars missions. Commercial space stations will soon join government outposts above Earth.

Understanding how our technology affects the space environment has never mattered more. An accidental barrier offers hope that we might one day build intentional protections. But it also warns us that consequences can travel farther than we expect, in directions we never considered, changing places we barely understand.